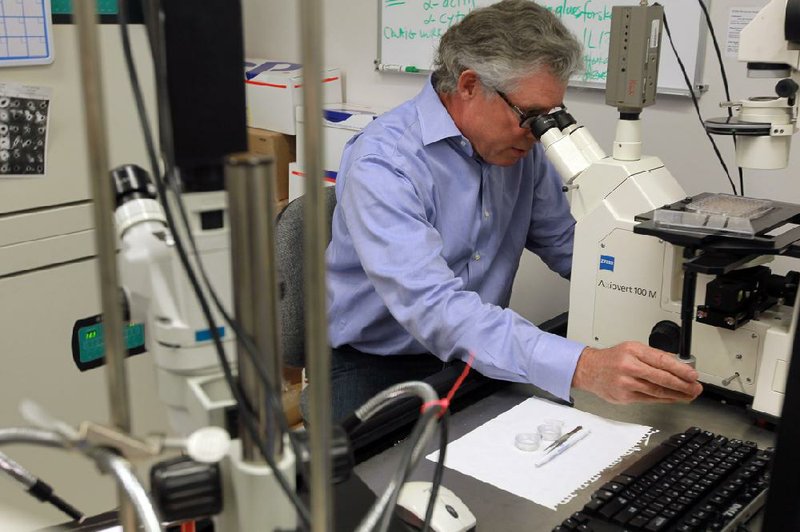

With his left hand on the edge of a microscope and his right hand tapping commands into a keyboard, cell biologist Dr. Richard Kurten nods to the computer screen.

The tissue under the microscope - a live, human lung - is reflected as a dark oval outlined with what look like tiny bubbles, pulsing to the rhythm of a beating heart.

Kurten turns his head, eyes wide and animated.

“There’s something special about life. I’m a scientist and I try to break things down, but this is just incredible,” said Kurten, a University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences researcher who has spent the majority of his nearly two-decade career studying respiratory biology, specifically the effects of asthma medications on the lungs.

Kurten’s small laboratory at the Arkansas Children’s Hospital Research Institute - which is supported in large part by proceeds from the Arkansas Tobacco Settlement - is one of only about five in the nation and about 10 in the world that conduct research on living lungs harvested from deceased human donors.

The silver-haired, blue jean clad scientist - who still uses a green chalkboard to map out his formulas - pointed to the corner of the lab where a cardboard box, stamped with “Left Lung,” sat on the floor.

Much like those on a transplant list, Kurten has to be ready at a moment’s notice for the call that a lung has become available. The organs - which usually come in pairs about the size of a half-gallon milk jug - are sent to Kurten’s lab only after they have been deemed not viable for transplant.

“I meet them at the airport usually. Sometimes they bring them to my house. Friday evenings are usually when we get them. Christmastime tends to be the busiest,” Kurten said.

Kurten became involved in the groundbreaking approach three years ago when a pharmaceutical company asked if his research findings could be replicated in humans instead of rats - which had thus far been the only option outside of actual human trials.

That was when Kurten contacted Dr. Reynold Panettieri Jr., director of Airways Biology Initiative at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Panettieri, who was in the very early stages of using the live, human lungs, supplied Kurten with his first test samples.

The two scientists quickly formed a strong collaboration that grew to an invitation from Panettieri for Kurten - as well as the Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, the University of South Florida in Tampa and Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore - to participate in an $11.9 million research grant from the National Institutes of Health.

The five-year grant awarded last year supports the group’s human-lung research on asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

“We had interesting results,” Kurten said. “We found out, ‘You know what? Rats are different from humans.’”

The use of human lungs is as close as a scientist can get without resorting to costly and potentially dangerous trials on human volunteers, Panettieri said.

“The rats do not typically mimic the disease in humans. This bridges the gap,” Panettieri said.

Kurten further humanizes his research by consulting with Dr. Stacie Jones, chief of pediatric allergy and immunology at UAMS. Jones gives Kurten real-time feedback on the issues and effects of medications she sees in her patients.

“The relationship is important because it keeps the research relevant,” Jones said. “This is amazing stuff. We’re looking at something as close to a whole-model system as we can get without going into humans.”

Kurten receives a new lung about every two to three weeks. He is currently on lung No. 95.

In the lab, Kurten runs his finger across the lines of a printed sign on the lab refrigerator. He gives the donor’s demographics: age, sex, race, cause of death.

He opens a binder with photographs and traces his index finger around a picture of a single lung. Much like a palm reader, he points to the lines and the shapes, telling a story.

“This guy cut grass for a living or worked in a railroad yard where there was a lot of diesel,” Kurten said, then his forehead creases as he flips through the other pictures.

“This is somebody’s son who got hit by a car. Someone’s wife, daughter, husband,” he said. “I feel like it’s our responsibility to go as far as we can with these lungs.”

On average, Kurten has about 18 hours from the time the lung is harvested until it can no longer be used.

He pointed to a white metal box that was mechanically moving from side to side, shaking the liquid-filled jars inside that contain lung samples.

“It helps to get a good exchange of nutrients,” Kurten explained, then used his fingers to count the other methods he is testing to maximize the life of the lungs.

Panettieri praised Kurten’s efforts and said that the techniques, while still a “work in progress,” are making a great impact.

Some lung samples can now be used two weeks after harvest. “Down the road,” Panettieri said, the techniques may result in lungs being frozen, then revived months, even years later.

Kurten further maximizes the use of the lungs by sharing unused samples with other researchers across the nation, including Dr. Daniel Voth, assistant professor and graduate program director for the department of microbiology and immunology at UAMS.

Voth studies the Coxiella burnetii infection - a condition commonly referred to as Q fever that originates in livestock and can be transferred to humans by inhalation of spores. The infection can cause severe upper respiratory problems for humans, among other complications, and can lead to inflammatory heart disease.

The partnership with Kurten has translated into Voth’s being the only Coxiella research lab in the nation to conduct studies on human cells.

“The ability to study the Coxiella infection in intact lung samples is a pretty novel thing. To be able to do this in the most natural setting possible, I think that’s where we’re going to learn the most,” Voth said.

Kurten said the opportunities brought by the research are endless and the findings and research techniques could possibly be replicated in other research areas.

“I think we are convincing others that their experiments can be done,” he said.

Front Section, Pages 1 on 04/13/2014