“All the little birdies on Jaybird Street love to hear the Robin go, ‘Tweet, Tweet, Tweet’” - “Rockin' Robin’ by Bobby Day, 1958

Ever wonder about the origin of the expression, “A little bird told me”? Jon Young thinks he knows.

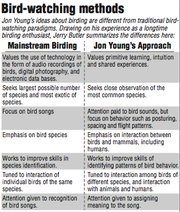

Young is an advocate for learning from the outdoors, an anthropologist and a naturalist with boyish enthusiasm for what he calls “deep bird language.” He spoke at the Audubon Arkansas Center in Little Rock on Sept. 16 at a book signing for his recently published work, What the Robin Knows (Mariner Books, 2013).

The signing was unique in the sense that there was only one copy of the book available for the 70 people in attendance to buy.

As an alternative to paper copies ($11.48), Young touted downloadable electronic books because they contain links to videos and graphs that illustrate the principles of deep bird language.

Young’s investigation into communication among birds, mammals and humans springs from a life-long involvement in ornithological pursuits.

He added to his personal experiences academic studies in ecology, natural science and anthropology at Rutgers University; extensive bird-watching on three continents; and interviews with San bushmen and bushwomen in the Kalahari desert of Botswana - for their primitive insight into birds.

Finally, more than 160 published scientific works are cited in his book to support his ideas.

According to Young, the essence of his ideas about observing nature can be summarized in three points:

1) Different species of birds talk to one another.

2) We can understand this bird talk.

3) It is fun to eavesdrop on what the birds are saying.

Young does not see himself as a “bird whisperer” but instead as a “bird listener.” He is a Dr. Doolittle with no tongue, but big ears and observant eyes.

Young says it is unnecessary to visit remote places or search for exotic species to make profound discoveries about bird meanings.

As the title of his book suggests, the American robin is a good teacher. The robin is easily recognized by most everyone and easy to observe in yards and parks.

He writes that this red-breasted harbinger of spring is a “handy” bird, with many vocally expressive whistles and a broad range of body language.

He also touts the abundant song sparrow and the junco (aka snowbird), as species that we could easily learn from.

WHAT JON KNOWS

For Young, the investigation into human understanding of wildlife is an enjoyable pastime and serious scientific inquiry. Among his tentative conclusions:

Humans can listen to birds singing, and with practice we can learn their meanings.

Bird meanings can be extrapolated from avian nonverbal behaviors (posturing, flight patterns, relative amount of activity, spacing of birds from one another, etc.) more so than from their whistles and tweets.

Primitive cultures are more adept in extrapolating bird meanings than advanced cultures, and the women in primitive cultures are more refined discerners of bird meanings than the men of those cultures.

Much of what the birds say relates to the location of mammals that are bird predators and to the movement of accipiters, the hawk-like birds that prey on songbirds. In Arkansas, and indeed most of the United States, the Cooper’s hawk is the most common accipiter.

By observing bird behavior, humans can accurately predict the movement and location of other birds and mammals.

Birds attach significance to the movement and postures of human beings.

MEASURING MEANINGS

Young and colleagues developed a method that allows trained observers, working in groups, to collect data about the behavior of wildlife and test the validity of various hypotheses about bird messaging. This method involves classifying avian behaviors into discrete categories that have descriptive names.

For example, “sentinel” is the behavior of a bird that perches high in a tree with an erect posture and stares toward the location of a predator, for instance, a Cooper’s hawk. Another bird (perhaps of a different species) might be a sentinel keeping an eye on the same hawk at a distance. By triangulation, the birds are telling other birds in the area the location of the hawk.

“Parabolic” is a pattern of bird behavior in which birds of different species arrange themselves in an arc or umbrella over an area of the forest floor and warn other birds and mammals that a predatory cat, fox or snake is lurking beneath the parabola.

“Popcorn” is the descriptive term Young has assigned to groups of small songbirds that fly up out of thick brush or shrubs and then drop quickly back into nearby areas of dense cover, like popcorn in a popper. This behavior means there is a weasel scurrying and darting about in the area. Young says a keen observer of deep bird language can discern whether it is in fact a weasel or some other varmint,like a nest-robbing rat or mink.

Analysis of a large number of these kinds of observations can demonstrate patterns of bird behavior that would be overlooked if made by a single observer.

At the book signing, Young received a strong round of applause when he announced that Little Rock had been chosen as one of 18 locations in the nation where a workshop teaching the methodology of deep bird research would be held in 2014. The workshop will be hosted by the Ozark Tracker Society, with help from Audubon Arkansas.

Jerry Butler is a frequent contributor to the Arkansas Democrat Gazette on topics related to birds. He welcomes stories about Arkansas birds at

ActiveStyle, Pages 27 on 09/30/2013