Big Bang writer straddles comedy, academia

Thursday, September 19, 2013

It may seem improbable that a network sitcom could revolve around the lives and loves of a group of scientists at the California Institute of Technology, or Caltech.

But The Big Bang Theory, which begins its seventh season Sept. 26 on CBS, is one of the most popular comedies on television. Part of its success might lie in the fact that its co-executive producer and chief script writer, Eric Kaplan, 46, knows comedy and academia. His resume includes not only The Simpsons and The Late Show With David Letterman, but also Harvard and a doctorate program - never completed - at the University of California, Berkeley.

Q: You grew up in Brooklyn, right?

A: I grew up in Flatbush. My mother was a biology teacher at Erasmus Hall. My father was a storefront lawyer. I got into Hunter High School when I was 12, and I took the subway to Manhattan.

Hunter was an awakening. I had friends from all over the city. During lunch hours, we’d go look at the arms and armor collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Like the characters in The Big Bang Theory, we played a lot of Dungeons and Dragons. I went to comic book conventions. I started reading philosophy pretty young.

Then I got into Harvard. My uncle said, “You should go to Harvard because they have a greater tolerance for weirdos than other schools.” And I said, “I’m not aware that I’m a weirdo.” And he said, “Uh-huh.”

Q: Was Harvard anything like your version of Caltech on The Big Bang Theory?

A: It was. Because you had people there who were sincerely and passionately interested in what they were doing. That world was about people so entrenched in whatever they were studying that they forget to put their pants on. Now, I don’t think I ever did that. But I’m sure I knew people who did.

The idea that you’re more interested in the amazing problems that life offers than in some kind of status game was genuine there, and that’s what we try to convey about the characters on the show.

Q: The Nobel Prize physicist Leon Lederman spent years trying to interest Hollywood in a television series featuring scientists. He got nowhere. How did Chuck Lorre, who first developed your series, get it done?

A: Well, Chuck Lorre is an incredibly accomplished and successful television producer. Leon Lederman shouldn’t feel bad. I bet if Chuck Lorre wanted to run an experiment on a particle collider, they wouldn’t let him.

Q: Lederman was told that nobody would want to watch a show about a bunch of nerds. Why was this assessment wrong?

A: I think that Chuck and Bill Prady, the show’s creators, figured out that the experience of being an outsider had universal appeal. The emotional pain at the heart of The Big Bang Theory is the feeling of being an outsider. Our characters, they don’t have to be scientists. They could be anybody who’s felt like an outsider.

Q: Aren’t you stereotyping scientists by labeling them as misfits?

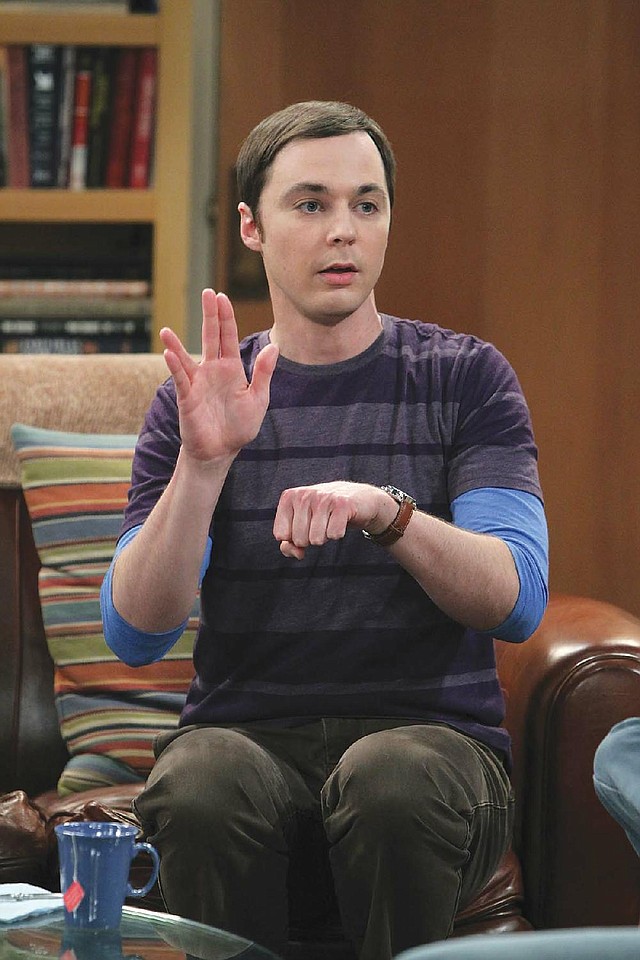

A: Listen, it’s a story, not a thesis about how everyone is. It’s a collection of specific characters. All scientists are not Sheldon Cooper, who finds it difficult to hug someone or go out to lunch and divide a check. But many people whose cognitive ability outstrips their emotional sense can see some aspect of Sheldon in themselves.

Q: How do you find the science content for your stories?

A: Well, let’s say we decide that Amy and Sheldon should have a fight. Since they’re scientists, their fight will be about science - about the relative priorities of neuroscience and physics. What’s going on emotionally is they’re arguing about the terms of their relationship, but they will cover it by expressing themselves about science. In that case, I wrote that scene because I have my own theories on that subject.

But in another situation, we could say we want Sheldon to be really angry about some branch of science he thinks is important, and he thinks others don’t understand. We’ll ask our science adviser, “What could that be?”

Q: Do you read the professional journals?

A: No, we read Science Times. We’ll come across stuff that seems worthwhile. The particle accelerator in Switzerland, there was some worry that it would destroy the universe. We probably made some joke about that or maybe even had a little plot line about it.

Q: How did you come to do the show?

A: I applied for a job.

Q: And … ?

A: I’d been working in television for a number of years. I wrote a script on speculation to get a job on Malcolm in the Middle, which I submitted to Chuck and Bill as a sample. And they interviewed me.

Q: Do you get fan mail from scientists?

A: We don’t just get mail. Scientists will come to the show and sit in the audience. We’ll often use them as extras in the background during cafeteria scenes.

Stephen Hawking came once. He was happy to portray a version of himself who was petty and childish and enjoyed humiliating Sheldon at a game of online Scrabble. He played himself as a big baby. He didn’t feel like he had to portray himself as a hero of science. That made me respect him even more, because he doesn’t feel the need to pretend to be anything.

Q: Your stories have a lot of insider jokes; there was a hilarious episode that included references to Schrodinger’s cat. How does your team know what’s funny in science?

A: I went to grad school in analytic philosophy, which is culturally very much like science. We talk to our science adviser, David Saltzberg, a physics professor at UCLA. We visit various schools and labs.

Once we went to the control station for the Mars rover. That was the source of a number of stories for Howard [Wolowitz].

We talked with a NASA astronaut, Mike Massimino. He told us about his Italian relatives who were unimpressed that he’d gone into space. There was one relative who was, “We usually make the new guy clean the garbage truck. You shouldn’t have to go out to the space station if you’re the senior guy.” So that became the story line for Howard. He goes into space, and no one in his daily life is impressed.

Q: Do you sometimes hear from scientists who say, “Thank you for showing something about our lives”?

A: Oh, yeah. They’ll sometimes say that there will be a new generation of scientists 10 years from now: kids who watched the show and decided to become scientists because they liked the characters. That would be great. I think there should be more scientists and fewer lawyers. It’s better to invent a plastic airplane than to sue somebody.

Style, Pages 31 on 09/19/2013