Rolling to a stop

Little Rock bus driver/dispatcher puts brakes on 65-year career

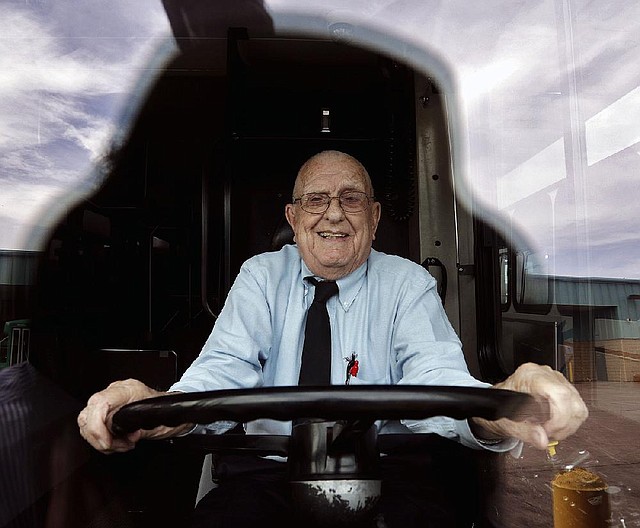

Tommy DeVore takes his old-time place behind the steering wheel of a Central Arkansas Transit Authority bus. DeVore started his 65-year career as a driver for the transit system. “I just loved the driving part,” he says on the way to his next stop: retirement.

Sunday, November 10, 2013

Tommy DeVore has done just about everything to do with buses. The Little Rock bus driver, dispatcher and public transit historian claims he is retiring after 65 years - five times longer than the average city bus stays on the job.

“I just loved the driving part,” DeVore says.

“You’re more or less your own boss out there so long as you’re doing what you’re supposed to be doing.”

He will pull the cord to stop Nov. 17, retiring at 84. But those who know him at the Central Arkansas Transit Authority office in North Little Rock say no one will be surprised if DeVore stays on.

He retired once before, after all, in 2004, and look where the ride took him: right back to a three day-a-week job in the dispatch office.

There, he tracks the whereabouts of 47 buses by means of computers and other electronics. He remembers when a driver whose bus broke down had to find a pay phone to report the trouble.

DeVore is such a legend among other bus guys, they rub the silvery bristle of his head for good luck. But he is more than a token of history.

“The dispatcher is ultimately the response person for an emergency,” says Bill Adcock, director of operations, one of DeVore’s old jobs among many.

“He’s held just about every position in the transit system,” say Sharon Williams, director of administration. “They say he was conceived in the back of a trolley car. He’s one of the best people we’ve got. Snow, rain or sleet, he’s here.”

Along the way, DeVore has collected hundreds of historical photos, newspaper clippings and bus tokens that tell how people got around places in Arkansas since early on.

The story begins with horse-drawn streetcars in Little Rock, North Little Rock, Hot Springs, Fort Smith and elsewhere across the state. Horse- and mule-drawn public transportation gave way to electric-powered streetcars, then passenger buses.

Even progress runs on a loop when it comes to buses, and so it wheels around to the latest thing in community development: streetcars.

CATA’s River Rail streetcar line follows the route of many other cities that have kept or brought back streetcars. San Francisco and New Orleans are famous for streetcars.

“Municipalities large and small across North America are more than willing to consider streetcars not as quaint relics, but as part of their 21st-century package,” according to Railway Age magazine.

This is where DeVore hops on. The man loves streetcars, always did.

“I’ve known Tommy since 1976, when I got here,” Adcock testifies, “and his passion has always been streetcars.”

Tennessee Williams wrote A Streetcar Named Desire in 1947. DeVore was 18 that year, and already knew how to drive one.

One reason DeVore is retiring is to build a proper model trainlike layout, where he intends to run his years-in-the making fleet of toy streetcars.

That tale about DeVore having come from a streetcar? Well, maybe not exactly, but it’s about as close to the truth as a quick walk to the nearest bus stop.

CLANGS FOR THE MEMORY

“I remember the first streetcar I ever saw,” DeVore says. “It was car No. 227 at Main and Markham,” downtown Little Rock.

This was about the time that his father, Thomas B. DeVore, and uncle, Andrew DeVore, started driving streetcars, 1936. Other boys dreamed of Buck Rogers rocket ships. But this lad was smitten with streetcars at age 7.

The car passed him by that fateful day like a metaphor of bad timing.

Little Rock had quit running streetcars by the time DeVore took the steering wheel, 1948. The transit system’s River Rail streetcar route between Little Rock and North Little Rock dinged into service in 2004, the same year he retired (the first time).

He never ran a streetcar in Little Rock the way his father did, but he found another way:

“Illegally.”

“I grew up in the [streetcar] shop more than I did at home,” DeVore says. Those days, he knew big guys who would let him drive for the heck of it.

The lever on the left, they showed him - that’s go. The one on the right is the brake. Pull the brake lever, it releases sand on the rails. The wheels need grit to stop.

Such were the physics of streetcar driving that came into play on the steep slope of Little Rock’s Cantrell Hill, headed down from the Heights. Mischief-makers liked to soap the rails.

Done right, the trick made for a lurch-and-slide descent as the streetcar driver hilariously dumped sand to gain friction. But who would do such a thing? What rascal knew how?

“I ain’t gonna say,” is DeVore’s answer.

JUST ONE OF THOSE DINGS

Cities across the country swapped streetcars for buses at the end of World War II, Adcock explains.

Factories had been in high gear building military vehicles. After the war, they turned to making city buses around the spare transmissions and other parts they needed to use up.

Buses were a bargain at $6,000 for a 35-foot-long set of wheels, about $56,000 in today’s money. A new bus costs about $350,000 these days.

These were the economics that placed DeVore in the driver’s seat of a bus instead of a streetcar. An actual seat is one advantage of the bus.

A streetcar driver generally stands, hands on the levers. A foot pedal works the clang clang bell.

The bus driver sits. In today’s bus, the seat sighs down to a comfortable height, the transmission is automatic and power steering takes the strain out of a turn.

But one thing hasn’t changed since DeVore’s time of looking out the vast windshield: The driver makes the same loop over and over. One way or another - maybe like a stage actor playing the same part every night - he has to find some way to keep the job interesting.

DeVore’s secret to 15 years as a driver was observation.

“Something happens every time,” he says. “Something else happens the next time.”

He collected 10 cents a ride. Today’s fare is $1.35. Today’s drivers tell him some people think the world owes them a free bus ride, and they mean to have it. Back then, they dropped a dime or a token in the box, he says, and they sat down.

He watched for his regulars, especially the traveling man. Out of town, this guy would ride the bus just to bring DeVore another souvenir - a bus schedule, a token, the early makings of DeVore’s bus memorabilia collection.

He keeps bus tokens like rare currency in the plastic pockets of coin album pages. Yesterday’s bus riders bought tokens the same as today’s buy passes.

These nickel- and dime-size slugs were good for a ride in Pine Bluff, Tulsa, Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, even Honolulu.

Tokens of a different kind - the routes he drove, the people he met, the changes he saw in everything from race relations to bus technology- all these, he stores in memory.

BUS STOP

DeVore liked driving so much, he says, “it was a long time before I made up my mind to come in the office.”

Now, as retirement day approaches like a bus to the bench - as he collects hugs and handshakes the way he used to pick up fares - he wonders if he really wants off.

A chat between him and the boss, Adcock, goes like this:

“I’m gonna sit and watch TV,” DeVore says.

“I’ve known you for 37 years,” Adcock says. “I don’t believe you’re going to sit and watch TV, Tommy.”

“Are you going to bar me if I come around once in a while?”

“No, I never will.”

“Well, you might see me.”

But maybe not - maybe DeVore is off the bus for good this time. On that chance, there’s only one thing to do.

Adcock gives DeVore’s silver-bristly head a rub while the opportunity remains “to get a little luck.”

Style, Pages 53 on 11/10/2013