Chief executive pay has been going in one direction for the past three years: up.

The head of a typical large public company made $9.7 million in 2012, a 6.5 percent increase from a year earlier, aided by a rising stock market, according to an analysis by The Associated Press using data from Equilar, an executive pay research firm.

Pay for chief executive officers, which fell two years straight during the 2008-09 recession but rose 24 percent in 2010 and 6 percent in 2011,has never been higher.

Companies say they need to pay chief executive officers well so they can attract the best talent, and that higher pay is ultimately in the interest of shareholders. But shareholder activists and some corporate governance experts say many chief executives are being paid far above what is reasonable or what their performances merit.

Pay for all U.S. workers rose 1.1 percent in 2010, 1.2 percent in 2011 and 1.6 percent last year - not enough to keep up with inflation. The median wage in the United States was about $39,900 in 2012, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

After years of pressure from corporate governance activists unhappy about big payouts, many companies have revamped their compensation formulas. They have awarded a bigger chunk of compensation in stock to align pay more closely to performance; have become more transparent about how compensation decisions are made; and, in some cases, have promised to claw back pay from fired executives.

Shareholder activists say the changes are a step in the right direction, yet they argue that chief-executive pay remains too high and that there is still too much incentive to focus on short-term results.

To calculate pay, Equilar looked at salary, bonus, perks, the potential future value of stock awards and option awards, and other pay that companies have to report for their top executives in regulatory filings each year. This year’s study examined pay for 323 chief executives at S&P 500 companies that had filed their shareholder proxies by April 30. The sample includes only chief executives in place for at least two years.

Sixty percent of chief executive officers received a raise, 37 percent got a pay cut and the rest had pay that was virtually flat.

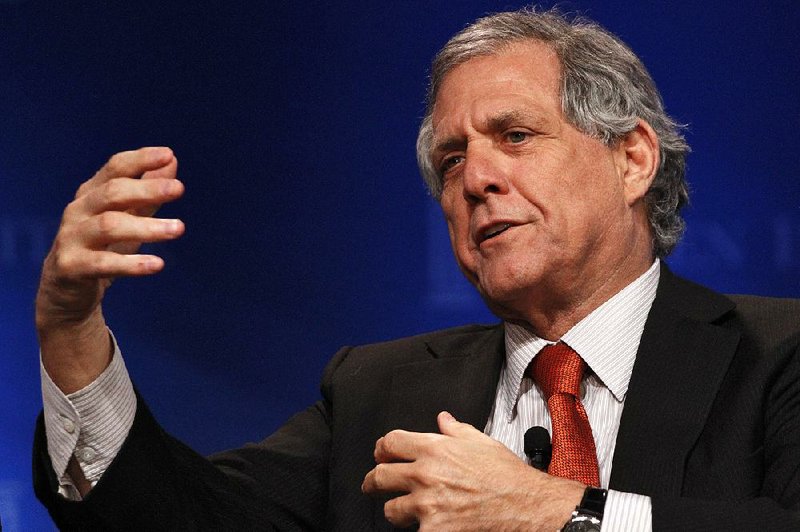

The highest-paid chief executive officer was Leslie Moonves of CBS, who made $60.3 million. He beat the second-place finisher handily: David Zaslav of Discovery Communications, who made $49.9 million. Five of the 10 highest-paid chief executives were from the entertainment and media industry.

For the fourth year in five, health-care chief executive officers received the highest median pay at $11.1 million, while utility chiefs had the lowest at $7.5 million. The median value is the midpoint, with half the chief executives in a group making more and half less.

The median pay for women chief executives was higher than it was for men - $11.2 million compared with $9.6 million - although only 3 percent of the companies analyzed were run by women. Irene Rosenfeld of Mondelez International, the snack giant that was spun off from Kraft Foods last year, was the highest-paid female chief executive officer, taking in $22 million.

The biggest changes in compensation last year came from stock, which increased 17.2 percent, and from stock options, which declined by 16 percent. Over the past five years, the amount of compensation that comes from stock has risen from 31.7 percent to 44.3 percent, while the amount from stock optionshas fallen from 31.9 percent to 17.6 percent. Shareholders tend to favor stock compensation because it can be tied to metrics like revenue and earnings, whereas the value of stock options depends only on the stock price.

Salaries and perks rose last year, while bonuses fell. As a proportion of total pay, bonuses accounted for 23.8 percent, salaries 10.4 percent and perks 3.8 percent.

The third-straight year of rising pay coincided with an improving economy and an increase in corporate revenue, profits and stock prices. The S&P 500 index rose 13.4 percent last year. The median profit increase at the companies in the Equilar study was 6.1 percent, and the median revenue gain was 7.6 percent.

With the economy on steadier footing and the stock market surging, the debate over chief-executive pay is settling into more of a simmer than a boil. Companies cut the pay of chief executives in 2008 and 2009 amid investors’ anger over the losses they had suffered during the financial crisis. Since 2011, they have been required by law to hold “say on pay” votes,which give shareholders the right to express whether they approve of a chief executive’s pay. The vote is nonbinding, but companies don’t want to deal with the public embarrassment of a “no.”

So far this year, only 14 U.S. companies have had shareholders vote down their executive-pay packages, according to proxy adviser Glass Lewis. That compares with 56 companies all last year. Even that number was tiny in relative terms - because it came from a sample of 2,100 companies. Some high-profile companies that lost their “say on pay” votes last year, including Citigroup, Big Lots and Chesapeake Energy, have gotten new CEOs since then.

Companies say they are listening to their shareholders’ concerns. They point to changes in how chief executives are rewarded that are meant to tie pay more closely to company performance. For example, they’re more often linking stock awards to revenue, earnings and share price targets, rather than just handing them out automatically.

“I’ve never seen an environment where boards take more time trying to get this right,” says Charlie Tharp, chief executive officer of the Center on Executive Compensation, an advocacy group that supports corporations.

Pay is up partly because a bigger proportion is coming from stock, and stock markets are hitting all-time highs. But it’s a two-way street: If stock markets decline, pay could decline or at least grow more slowly in future years.

But changing the pay structure has hardly silenced the critics. They say formulas for stock awards, for example, can drive chief executive officers to focus on short-term results. And they’re anxious for the Securities and Exchange Commission to implement a rule required under the Dodd-Frank financial revisions law that would force big public companies to disclose the ratio of their chief executive’s pay compared with the median pay for their entire work force.

“If you’re making $10 million a year, you get into a situation where life isn’t real anymore,” said Eleanor Bloxham, chief executive of the Corporate Governance Alliance, which advises boards.

Charles Elson, a wellknown shareholder rights expert who is director at the Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware, has been crusading for companies to stop compensating their chief executive officers based on what their peers at similar companies are making.

The trouble with peer groups, Elson said, is that a chief executive could have a terrible year, “but if my peer’s pay goes up, my pay will too.”

Business, Pages 67 on 05/26/2013