New book hails a trailblazer

Sunday, May 12, 2013

Correction: Hattie Caraway was appointed by the governor to fill the U.S. Senate seat of her late husband until a special election could be held to decide who would finish the term. She began serving on Dec. 9, 1931, and won the January 1932 special election. Caraway ran three times for full terms, winning in 1932 and 1938 but losing in 1944. This article incorrectly listed the date of the special election and incorrectly stated how many times she sought full terms.

It still seems remarkable that the first woman ever elected to the U.S. Senate came from Arkansas, traditionally a state where men were men - and women were expected to know their place: rocking the cradle and baking the cornbread.

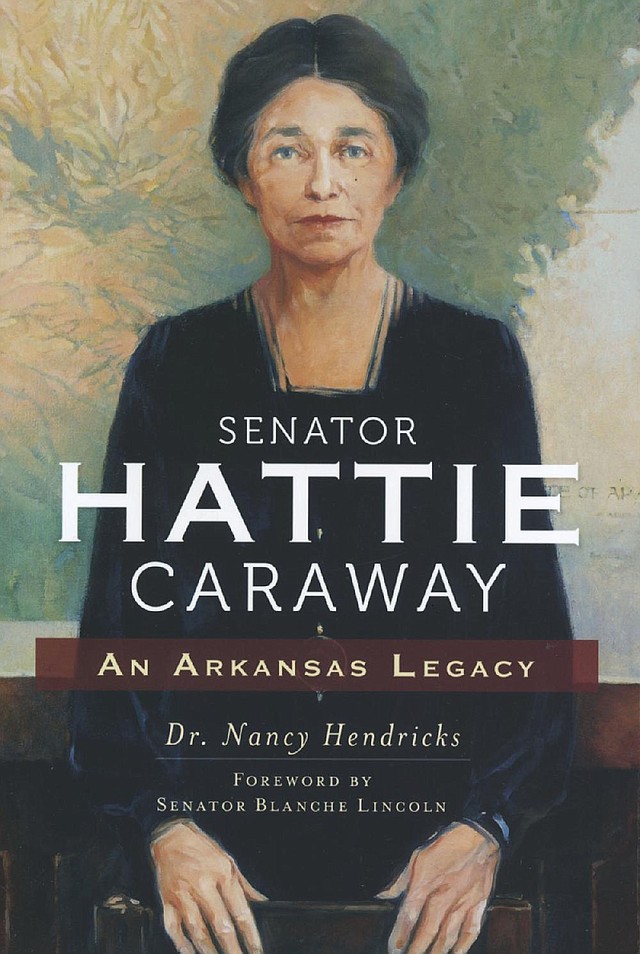

Hattie Wyatt Caraway was the U.S. senator in question, and her nonpareil story is told in a pithy new biography by Nancy Hendricks, formerly a professor and administrator at Arkansas State University at Jonesboro.

The 128-page volume is Hendricks’ second book about Caraway, whom the Jonesboro author has practically adopted as a persona. She has created and performed in three one-woman plays, along with a television documentary, about the senator, who was appointed to complete her late husband’s term in Washington in 1931 before winning full six-year terms in 1932 and 1938.

Hendricks’ first paragraph in Senator Hattie Caraway: An Arkansas Legacy, published by History Press as a $19.99 paperback, suggests how far ahead of its time the widow’s election was:

“In those days, the private restroom just off the Senate chamber was labeled ‘Senators,’ which meant males only. The lone woman senator was forced to leave the Senate, traverse the long corridors of the Capitol, mingle with the crowds and utilize the public facilities used by hundreds of tourists.”

Caraway’s achievement in winning a full Senate term the year Franklin D. Roosevelt was first elected president is highlighted by the fact that no other woman managed to do so until Margaret Chase Smith of Maine in 1948. Arkansas’ only other female senator has been Blanche Lincoln, elected in1998 to the first of two terms before losing in 2010. (Lincoln contributed the foreword to this book.)

Nationwide, just 31 women have ever been voted to six year terms in the Senate, while another 13 served more briefly by appointment or special election. The current Senate boasts 20 women - the most ever - but still merely 20 percent of the total.

And, as Hendricks’ book points out, women serving in the Senate did not get their own restroom until 1993.

While the biography qualifies as a paean to its subject, it is not a hagiography. Hendricks writes that Caraway “did not photograph well. She was tiny, round, loved to eat and was hardly stylish. Some called her dour and dowdy. But while she famously always wore black, she painted her long fingernails bright red.”

She rarely made a Senate speech, giving rise to the dismissive nickname “Silent Hattie.” Flourishing what seems to have been a deft sense of humor, she once explained her reticence to speak as reluctance “to take a minute away from the men. The poor dears love it so.”

Caraway did advocate one peculiar piece of legislation, which she introduced several times without success. It would have required every commercial aircraft to carry a parachute for each passenger.

And, like all senators of the time from former Confederate states, she voted against proposed anti-lynching legislation. She also seems to have had mixed feelings about women’s right to vote, once writing, “After equal suffrage, I just added voting to cooking and sewing and other household duties.”

“While not excusing her vote on the anti-lynching issue,” says Hendricks, “one might also point out that she was a strong early supporter of federal aid to education to help poorer states like Arkansas. She also backed the G.I. Bill of Rights and an Equal Rights Amendment for women,” a clear departure from her earlier facetious comment about voting.

Born in Tennessee in 1878, the future senator earned a bachelor’s degree and taught school before marrying Thaddeus Horatius Caraway. The couple moved to Arkansas, where he established a law practice in Craighead County while she reared their three sons, two of whom became Army generals.

Thad was elected in 1912 to the first of four terms in the U.S. House of Representatives and then in 1920 to the Senate. Re-elected in 1926, he was near the end of his second term when he died of a blood clot in November 1931.

Appointed to her husband’s seat, Hattie was expected to follow the brief path of the one previous female senator. Rebecca Latimer Felton, widow of a Georgia congressman, had been similarly appointed in 1922. She served for a single day before stepping down.

But Caraway decided to run in the Dec. 9, 1931, special election. She kept her seat for the last year of her husband’s term, then swept to a full term in 1932 by winning the Democratic Party primary against six male opponents, tantamount then to victory in the basically one-party South.

In 1938, she defeated future Sen. John L. McClellan, who campaigned with the chauvinist slogan “Arkansas needs another man in the Senate.” Seeking a third six-year term in 1944, she lost to the legendary J. William Fulbright.

Hendricks’ book surmises why Caraway decided to run twice for a full term after the year spent filling her husband’s seat:

“At least part of it had to be because she saw her male colleagues acting uncouth, dressing sloppily, speaking poorly, lapsing in attendance and sleeping at their desks. Perhaps her ‘theory’ was that a woman with common sense could be just as good as a man in the Senate - and certainly no worse.”

As to why Caraway managed to overcome the longstanding bias against women in elective office, Lincoln writes in the foreword: “It was not only a testament to the open-mindedness and fairness of the people of Arkansas, but also to the kind of woman Hattie Caraway was.”

Hendricks adds that “Hattie would be the first to credit the results of the 1932 election to the colorful, controversial Huey Long [of Louisiana] who barnstormed the state on her behalf. The results of her 1938 re-election could be attributed to her unceasing help on an individual basis for the Depression-stricken people of Arkansas. She simply never forgot the people back home.”

After her 1944 loss to Fulbright, Caraway worked for a federal agency in Washington until suffering a stroke in early 1950. She died at age 72 on Dec. 21, 1950, and is buried next to her husband in Jonesboro’s Oaklawn Cemetery.

Hendricks cites one comment from Caraway as summing up the late senator’s no-nonsense approach to public service: “If I can hold on to my sense of humor and a modicum of dignity, I shall have had a wonderful time running for office, whether I get there or not.”

Hendricks will sign copies of her book Saturday from 1 to 2:30 p.m. at Words Worth Books, 5920 R. St., Little Rock; for details, call the store at (501) 663-9198. Signings are being planned for other locales.

Style, Pages 49 on 05/12/2013