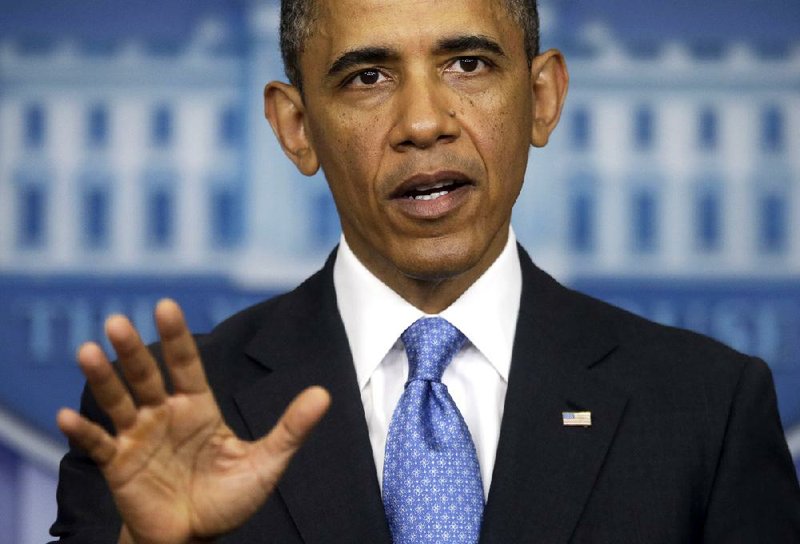

WASHINGTON - President Barack Obama on Tuesday recommitted to his years old vow to close the prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, after the arrival of “medical reinforcements” of nearly 40 Navy nurses, corpsmen and specialists amid a mass hunger strike by inmates who have been held for more than a decade without trial.

“It’s not sustainable,” Obama said at a White House news conference.

“The notion that we’re going to keep 100 individuals in no-man’s land in perpetuity,” he added, made no sense. “All of us should reflect on why exactly are we doing this? Why are we doing this ?”

As a candidate for the White House in 2007 and 2008, Obama called for closing the base, which was set up as part of President George W. Bush’s response to the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Lawmakers objected, and the facility remains open.

Obama said Tuesday that he will reach out to lawmakers to try to shut it down.

“I’m going to go back at this,” he said. “I’m going to re-engage with Congress to try to make the case that this is not something that’s in the best interests of the American people.”

Citing the high expense and the foreign-policy costs of continuing to operate the prison, Obama said he would try again to persuade Congress to lift restrictions on transferring inmates to the federal court system. Obama noted that several suspected terrorists have been tried and found guilty in U.S. federal courts, an answer to his congressional critics who maintain that detainees must be tried in special courts if the United States is to maximize its ability to prevent future attacks.

He was ambiguous, however, about the most difficult issue raised by the prospect of closing the prison: what to do with detainees who are deemed dangerous but could not be feasibly prosecuted.

Obama’s existing policy on that subject, which Congress has blocked, is to move detainees to maximum-security facilities inside the United States and continue holding them without trial as wartime prisoners.

Yet at another point in the news conference, Obama appeared to question the policy of indefinite wartime detention at a time when the war in Iraq has ended, the one in Afghanistan is winding down and the original makeup of al-Qaida has been decimated. “The idea that we would still maintain forever a group of individuals who have not been tried,” he said, “that is contrary to who we are, contrary to our interests, and it needs to stop.”

But in the short term, Obama indicated his support for the force-feeding of detainees who refused to eat.

“I don’t want these individuals to die,” he said.

As of Tuesday, 100 of the 166 prisoners at Guantanamo were officially deemed by the military to be participating in the hunger strike, with 21 “approved” to be fed the nutritional supplement Ensure through tubes inserted through their noses. In a statement released earlier, a military spokesman said the deployment of additional medical personnel had been planned several weeks ago as more detainees joined the strike.

“We will not allow a detainee to starve themselves to death, and we will continue to treat each person humanely,” said Lt. Col. Samuel House, the prison spokesman.

The military’s response to the hunger strike has revived complaints by medical-ethics groups that contend that doctors - and nurses under their direction - should not force-feed prisoners who are mentally competent to decide not to eat.

Last week, the president of the American Medical Association, Dr. Jeremy Lazarus, wrote a letter to Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel saying that any doctor who participated in forcing a prisoner to eat against his will was violating “core ethical values of the medical profession.”

“Every competent patient has the right to refuse medical intervention, including life-sustaining interventions,”Lazarus wrote.

He also noted that the American Medical Association endorses the World Medical Association’s Tokyo Declaration, a 1975 statement forbidding doctors to use their medical knowledge to facilitate torture. It says that if a prisoner makes “an unimpaired and rational judgment” to refuse nourishment, “he or she shall not be fed artificially.”

The military’s policy, however, is that it can and should preserve the life of a detainee by forcing him to eat if necessary.

“In the case of a hunger strike, attempted suicide or other attempted serious self-harm, medical treatment or intervention may be directed without the consent of the detainee to prevent death or serious harm,” a military policy directive says. “Such action must be based on a medical determination that immediate treatment or intervention is necessary to prevent death or serious harm and, in addition, must be approved by the commanding officer of the detention facility or other designated senior officer responsible for detainee operations.”

On Monday, House said some detainees on the “enteral feeding” list were drinking the supplement.

“Just because the detainees are approved for enteral feeding does not mean they don’t eat a regular meal,” he said. “Once the detainees leave their cell and are in the presence of medical personnel, most of the detainees who are approved for tube feeding will eat or drink without the peer pressure from inside the cell block.”

Medical ethicists and the Pentagon also clashed during the Bush administration over hunger strikes at Guantanamo.

The current protest began in February and escalated after a raid last month in which guards confined protesting detainees to their cells. The impetus for it is disputed. The prisoners, through their lawyers, cite a search for contraband on Feb. 6, during which they say Korans were handled in a way they found offensive. The military said the Koran search followed routine procedures.

But both sides agree that the root cause is frustration over the collapse of Obama’s effort to close the prison, which drew congressional resistance, and the fact that no prisoners have been transferred because of restrictions on where they can be sent.

Congress has restricted the repatriation to countries with troubled security conditions, helping to jam up 86 low-level detainees who were designated for potential transfer three years ago; most are Yemeni. But since 2012, lawmakers have given the Pentagon the ability to waive most of those restrictions on a case-by-case basis, and it has not done so.

On Tuesday, Obama said, “I’ve asked my team to review everything that’s currently being done in Guantanamo, everything that we can do administratively.”

Sen. Patrick Leahy, a Vermont Democrat who heads the Judiciary Committee, endorsed Obama’s call for Guantanamo’s closing.

“In the years since Congress first blocked resolving this, the reasons for closing it have only multiplied,” Leahy said in a statement. “The deteriorating situation at Guantanamo, including the ongoing and expanding hunger strikes by prisoners - many of whom have never been convicted of any crime and are eligible for release - is disturbing and unacceptable.”

But the chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, Rep. Howard “Buck” McKeon, signaled that he is prepared to fight the proposal again.

“The president faces bipartisan opposition to closing Guantanamo Bay’s detention center because he has offered no alternative plan regarding the detainees there, nor a plan for future terrorist captures,” the California Republican said in a statement.

Ramzi Kassem, a City University of New York law professor who represents several detainees, said he had talked to a Yemeni client, Moath Hamza Ahmed al-Alwi, who said a guard had shot him with rubber-coated pellets at close range during the raid. Since then, Kassem was told, the prisoners have been denied soap, toothbrushes, toothpaste and their legal papers.

Al-Alwi said he had not eaten in 80 days and stopped drinking after the raid, Kassem said. He also said he was being force-fed twice a day after being tied to a restraint chair.

Kassem also quoted al-Alwi as saying: “I do not want to kill myself. My religion prohibits suicide. But I will not eat or drink until I die, if necessary, to protest the injustice of this place. We want to get out of this place. It is as though this government wishes to smother us in this injustice, to kill us slowly here, indirectly, without trying us or executing us.”

In his statement Monday, House said the prisoners would not be allowed to die.

“Detainees have the right to peacefully protest, but we have the responsibility to ensure that they conduct their protest safely and humanely,” he said. “Detainees are given a choice: eat the hot meal, drink the supplement or be enteral fed.” Information for this article was contributed by Charlie Savage of The New York Times; by Zachary A. Goldfarb of The Washington Post; by Julie Pace of The Associated Press; and by David Lerman of Bloomberg News.

Front Section, Pages 1 on 05/01/2013