Getting face-time with the family doctor stands to become even harder, healthcare officials say.

A shortage of primary-care physicians in some parts of the country is expected to worsen as millions of newly insured Americans gain coverage under the federal health-care law next year. Doctors could face a backlog, and patients could find it difficult to get prompt appointments.

Attempts to address the provider gap have taken on increased urgency ahead of full implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act on Jan. 1, but many of the potential solutions face a backlash from influential groups or will take years to bear fruit.

Lobbying groups representing doctors have questioned the safety of some of the proposed changes, arguing that they would encourage less collaboration among health professionals and suggesting that they could create a two-tiered health system offering unequal treatment.

Legislation seeking to expand the scope of practice of dentists, dental therapists, optometrists, psychologists, nurse practitioners and others has been killed or watered down in numerous states. Other states have proposed expanding student-loan reimbursements, but money for doing so is tight.

As fixes remain elusive, the shortfall of primary-care physicians is expected to grow.

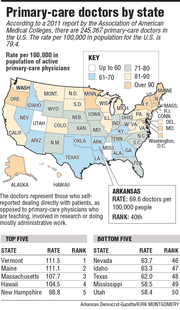

Nearly one in five Americans already lives in a region designated as having a shortage of primary-care physicians, and the number of doctors entering the field isn’t expected keep pacewith demand. About 250,000 primary-care doctors work in America now, and the Association of American Medical Colleges projects that the shortage will reach almost 30,000 in two years and will grow to about 66,000 in little more than a decade. In some cases, nurses and physician assistants help fill the gap.

In Arkansas, a study released in March by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement, a nonpartisan policy center led by state Surgeon General Dr. Joe Thompson, found that the state needs to increase its work force of 2,077 primary-care physicians by 15 percent to meet the current demand. The expansion of Medicaid to people with incomes of up to 138 percent of the poverty level will add the need for an additional 60 primary-care providers, the report found.

The state and national shortfall can be attributed to a number of factors: The population has both aged and become more chronically ill, while doctors and clinicians have migrated to specialty fields such as dermatology or cardiology for higher pay and better hours.

INNER CITIES, RURAL AREAS

The shortage is especially acute in impoverished inner cities and rural areas, where it already takes many months, years in some cases, to hire doctors, health professionals say.

“I’m thinking about putting our human-resources manager on the street in one of those costumes with a ‘We will hire you’ sign,” said Doni Miller, chief executive of the Neighborhood Health Association in Toledo, Ohio. One of her clinics has been trying to hire a physician for two years.

In Arkansas, the Center for Health Improvement report found severe shortages of physicians in the southeast and southwest corners of the state, while the central part had more physicians than needed to meet demand.

The report identified pockets of patients around the state who have to drive more than 30 minutes to see primary-care physicians and even farther to see specialists. Outside of the state’s population centers in Jonesboro, central and Northwest Arkansas, most patients have to drive an hour or more to reach a full complement of specialists.

Newton County, with a population of about 8,100, has one practicing primary-care physician, in Jasper.

“He’s busy all the time,” said Regina Tkachuk, administrator of the Department of Health’s health unit in the county. “It’s pretty hard to get in to see him.”

In southern Illinois, the 5,500 residents of Gallatin County have no hospital, dentist or full-time doctor.Some pay $50 a year for an air-ambulance service that can fly them to a hospital in emergencies. Women have their babies at hospitals an hour away.

The lack of primary care is both a fact of life and a detriment to health, said retired teacher and community volunteer Kappy Scates of Shawneetown, whose doctor is 20 miles away in a neighboring county.

“People without insurance or a medical card put off going to the doctor,” she said. “They try to take care of their kids first.”

In some areas of rural Nevada, patients typically wait seven to 10 days to see a doctor.

“Many, many people are not taking new patients,” said Kerry Ann Aguirre, director of business development at Northeastern Nevada Regional Hospital, a 45-bed facility in Elko, a town of about 18,500 that is a four-hour drive from Reno, the nearest major city.

Nevada is one of the states with the lowest per-capita rate of active primary-care physicians, along with Mississippi, Utah, Texas and Idaho, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges. In the association’s most recent ranking, in 2011, Arkansas ranked 40th with 69.6 primary-care physicians per 100,000 residents.

The problem will become more acute nationally when about 30 million uninsured people eventually gain coverage under the Affordable Care Act, which takes full effect next year.

“There’s going to be lines for the newly insured, because many physicians andnurses who trained in primary care would rather practice in specialty roles,” said Dr. David Goodman of the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice.

Roughly half of those who will gain coverage under the Affordable Care Act are expected to do so through Medicaid, the federal-state program for the poor and disabled. States can opt to expand Medicaid, and at least 24, including Arkansas and the District of Columbia, plan to do so.

The “private option” Medicaid expansion approved by the Arkansas Legislature in April will extend eligibility for the program to those with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level - $15,860 for an individual or $32,500 for a family of four. Those who qualify will be able to sign up for the coverage through private health-insurance plans and have their premiums paid by Medicaid.

In Ohio, which is weighing the Medicaid expansion,about one in 10 residents already lives in an area underserved for primary care.

Mark Bridenbaugh runs rural health centers in six southeastern Ohio counties, including the only primary-care provider in Vinton County. The six counties could see some of the state’s largest enrollments of new Medicaid patients per capita under the expansion.

As he plans for potential physician vacancies and an influx of patients, Bridenbaugh tries to identify potential hires when they start their residencies - several years before they can work for him.

“It’s not like we have people falling out of the sky, waiting to come work for us,” he said.

NO EASY FIXES

State legislatures working to address the shortfall are finding that remedies are not easy.

Bills to expand the roles of nurse practitioners, optometrists and pharmacists have been met with push-back in California. Under the proposals, optometrists could check for high blood pressure and cholesterol while pharmacists could order diabetes testing. But critics, including physician associations, have said such changes would lead to inequalities in the health-care system- one for people who have access to doctors and another for people who don’t.

In New Mexico, a group representing dentists helped defeat a bill that would have allowed so-called dental therapists to practice medicine. And in Illinois, the state medical society succeeded in killing or gutting bills this year that would have given more medical decision-making authority to psychologists, dentists and advanced-practice nurses.

Other states are experimenting with ways to fill the gap.

Texas has approved two public medical schools in the past three years to increase the supply of family doctors and other needed physicians. New York is devoting millions of dollars to programs aimed at putting more doctors in underserved areas. Florida now allows optometrists to prescribe oral medications - including pills - to treat eye diseases.

In Arkansas, four universities - the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, the University of Central Arkansas and Arkansas State University-Jonesboro - have added doctor-of-nursing-practice programs to add to the state’s number of well-trained advanced-practice nurses. And UAMS recently added a physician-assistant program.

Leaders at the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement have said advanced-practice nurses should be seen as complements to physicians rather than alternatives with less training. Arkansas’ scopeof-practice laws require advanced-practice nurses to consult with physicians in order to write prescriptions, and a series of new initiatives encourage medical professionals of all types to work as a team to strengthen the care they provide to patients.

Craig Wilson, the center’s director of access to quality care, said increasing the number of people with insurance under the Affordable Care Act could attract doctors to work in underserved areas.

”Where you had before upwards of a third of a county’s population who couldn’t pay for medical services, now you’re going to have a great increase in the ability of those individuals to pay for services,” Wilson said.

The state’s patient-centered medical-home initiative, in which doctors, nurses and other providers receive extra payments as an incentive to work as a team and provide extra services, could also help increase access to health care by reducing duplication andallocating tasks more efficiently, Wilson said.

The federal law also attempts to address the anticipated shortage by including incentives to bolster the primary-care work force and boost training opportunities for physician assistants and nurse practitioners. It offers financial assistance to support doctors in underserved areas and increases the level of Medicaid reimbursements for those in primary-care practices.

John Atlas, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, said he expects nurse practitioners and physician assistants to meet the increase in demand for the diagnosis and treatment of simple ailments. He said he’s more concerned about how “ramping down” reimbursements will affect doctors and hospitals, combined with increased regulation.

RESIDENCY SHORTFALLS

And many would-be doctors will face hurdles before they finish training.

Residency positions, the final step in the path to becoming a fully independent physician, are increasingly limited. The number positions - funded through the federal Medicare program - has been capped for years. Meanwhile, medical-school admissions continue to grow, and foreign graduates are increasingly competing for U.S. positions.

This spring, 34,355 students nationwide were “matched” with residency positions based on students’ preferences and position availability, according to the National Residency Matching Program, and 8,800 others nationwide failed to get accepted through the program. As many UAMS graduates learned of their residenciesthis year, nine of their peers did not receive residency positions. Many of those students will complete research work and try to match again in the future, but there are no guarantees they will find a placement.

But those medical school graduates who do “match” face a ready job market.

Providers are recruiting young doctors as they gear up for the expansion.

Stephanie Place, 28, a primary-care resident at Northwestern University’s medical school in Chicago, received hundreds of e-mails and phone calls from recruiters and health clinics before she accepted a job this spring.

The heavy recruitment meant she had no trouble fulfilling her dream of staying in Chicago and working in an underserved area with a largely Hispanic population. She’ll also be able to pay off $160,000 in student loans through a federal program aimed at encouraging doctors to work in areas with physician shortages.

Place said the federal law turned needed attention to primary care as a specialty among medical students.

“Medical students see it as a vibrant, evolving, critical area of health care,” she said.

Even so, many experts say the gap will not close quickly between doctor availability and those gaining care under the health-care act in many parts of the country. Access to care could get worse for some people before it gets better, said Dr. Andrew Morris-Singer, president and co-founder of Primary Care Progress, a nonprofit in Cambridge, Mass.

“If you don’t have a primary-care provider,” he said, “you should find one soon.” Information for this story was contributed by Ann Sanner, Sandra Chereb, Carla K. Johnson, Kelli Kennedy, Judy Lin, Barry Massey, John Seewer, Chris Tomlinson and Michael Virtanen of The Associated Press; and by Andy Davis, Evie Blad and Jacy Marmaduke of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

Front Section, Pages 1 on 06/23/2013