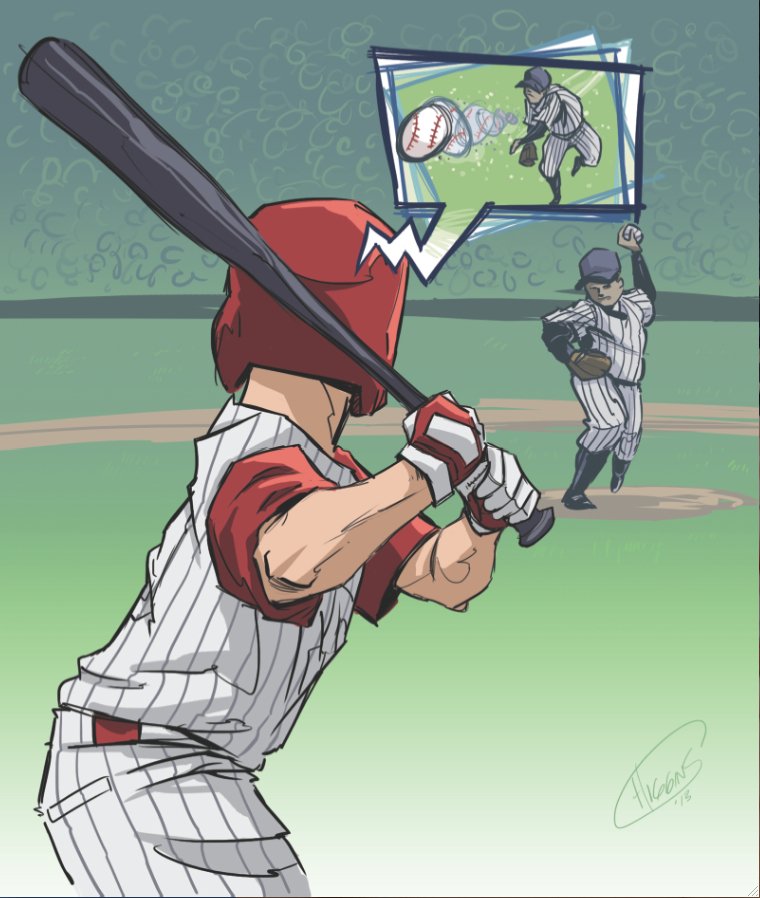

The human brain is far slower than a major league fastball or a blistering tennis serve - but it has figured out a workaround.

New research by University of California-Berkeley scientists solves a puzzle that has long mystified anyone who has watched, in awe, as elite athletes respond to incoming balls that can surpass 90 mph.

The brain perceives speeding objects as farther along in their trajectory than seen by the eyes, giving us time to respond, according to research by Gerrit Maus, lead author of a paper published May 8 the journal Neuron.

This clever adjustment - compensating for the sluggish route from the eyes to neural decision-making - “is a sophisticated prediction mechanism,” he said. “As soon as the brain knows something is moving, it pushes the position of the object moving forward, so there’s a more accurate measure of where this object actually is.”

This is useful in survival situations far more important than sports - such as when we’re crossing a street, in front of a speeding car.

Former Yankees catcher Yogi Berra pondered the mystery, once asking: “How can you think and hit at the same time?”

You can’t, because there’s not time for both.

“But you don’t need to think about it, because the brain does it automatically,” Maus said.

At the average major league speed of 90 mph, a baseball leaves the pitcher’s hand and travels about 56 feet to home plate in only 0.4 seconds, or 400 milliseconds.

Tennis is even faster. In May, court side radar guns measured a serve by British player Samuel Groth at 163 mph.

In that split second, there’s a lot of work for the body to do. Eyes must first find the ball. The sensory cells in the retina determine its speed and rush this information to the brain. Then the brain sends messages through the spinal cord that tell muscles in the arms and legs to respond.

“By time the brain receives the information, it’s already out of date,” Maus said.

The researchers said it can take one-tenth of a second for the brain to process what the eye sees. By the time the brain “catches up” a fast-moving tennis or baseball would already have moved 10 to 15 feet closer.

A region in the back of the brain, called area V5, computes motion and position - and projects where it thinks the ball should be, rather than where the eyes saw it.

For the experiment, six volunteers had their brains scanned with a functional MRI as they viewed the “ flashdrag effect,” a two-part visual illusion in which we see brief flashes shifting in the direction of a motion.

The researchers found that the illusion - flashes perceived in their predicted locations against a moving background and flashes actually shown in their predicted location against a still background - created the same neural activity patterns in the V5 region of the brain.

The finding could also help explain why altered trajectories can fool us - such as tennis back spins or baseball pitches with so-called late break.

People who cannot perceive motion cannot predict locations of objects and therefore cannot perform tasks as simple as pouring a cup of coffee.

“The brain doesn’t work in real time,” Maus said.

ActiveStyle, Pages 27 on 06/10/2013