Hugh Pollard, 72, of Little Rock, hasn’t taken a bad spill yet. He’s hoping he never will. But about six months ago, he began to suspect that his balance wasn’t what it once was, so he tested himself by standing on one foot.

The exercise only lasted a few seconds, and that alarmed him.

He mentioned his concern to Dr. Stephen Tucker, his general physician. “He’s a real expert, I think, in matters of athleticism.

He told me the key to balance is to strengthen your legs,” Pollard says.

Pollard was right to be concerned. According to the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a third of all adults over 65 will fall this year, and falls are the leading cause of death due to injury among this age group. But balance disorders can affect people of any age, and they can baffle patients and care providers alike.

Dr. John Dornhoffer, an otolaryngologist (ear, nose and throat specialist) and director of the hearing and balance center at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, remembers going to a medical conference in the late ’80s at which a researcher named John Epley explained what he believed was a simple treatment for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. This is a condition in which patients experience spinning to the point that they can’t stand or sit up. Otolaryngologists knew it had something to do with “rocks in the ear,” or rather, the displacement of tiny calcium carbonate crystals in an inner ear pouch. The accepted treatment was invasive, often resulting in hearing loss.

Epley thought, if the crystals get knocked out of place, why not knock them back? He demonstrated his theory with a few simple head rotations. “Everybody laughed him off the stage,” Dornhoffer says.

Dornhoffer was skeptical as well, but he tried the procedure on an elderly woman. They were both shocked when it worked.

His patient told one of Dornhoffer’s colleagues, “This doctor puts his hands on my head, and my vertigo is gone. I think he’s Jesus Christ!” But no, it wasn’t a miracle, just mechanics.

Vertigo is one of the most common complaints that send patients to Dornhoffer. And these days, canalith repositioning, otherwise known as the Epley Maneuver, is universally accepted as a cure for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

But the Epley Maneuver only addresses one of a myriad of conditions that may lead to instability. Trauma, tumors, peripheral nerve damage (often due to diabetes), chronic ear infections, vascular issues and certain medications are culprits, as are neurological conditions, cervical joint dysfunction and vestibular mismatch - when someone’s eyes and inner ears receive conflicting information.

Or the problem may be muscle atrophy, a common aspect of aging.

Tucker recommended that Pollard see physical therapist Michael DuPriest, who explains the ability to maintain balance as a complex relationship between three separate body systems:

Visual (information from the eyes).

Somatosensory (nerves and spatial awareness).

Vestibular (the inner ear).

If any one system is compromised, the other two will compensate. But if two of the three are compromised, the threat of falling is significantly heightened.

When patients complain of instability, the 14-item Berg Balance Scale is a commonly used assessment test. It includes observing patients as they stand on one foot, stand with their eyes closed, make a full turn and reach forward with an outstretched arm. But DuPriest uses a simpler method called the “Up and Go Test.”

He times patients as they rise from a chair, walk forward 10 feet, return and sit down. Healthy people should be able to accomplish this task in 20 seconds or less.

Usually DuPriest assigns the patient exercises to strengthen muscles and improve coordination. Activities that target the hips, core, feet, ankles and legs are helpful, as well as motions that require quick shifting, such as jumping or catching a weighted ball.

“With the elderly, it’s in the hips. So one of the things that helps is to stand up from a chair without pushing with your arms,” DuPriest says.

He also likes to keep it short, a handful of exercises or fewer. His motto is: “Simple leads to compliance.”

Pollard sees DuPriest twice a week and spends about 45 minutes a day exercising. In just a few months, he has noticed progress. “I stood on one leg for 45 seconds the other day,” he says.

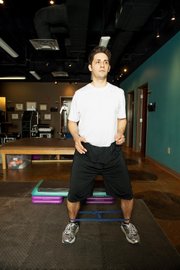

DuPriest’s technician, Alex Rosa, demonstrates exercises with names like Clam Shell and Bridge. But if DuPriest were to choose three of the most helpful, he would go with:

The Flamingo - in which the patient stands on one foot for 60 seconds. DuPriest recommends lightly pressing fingertips against a wall or chair, if necessary. It’s OK to cheat and touch down, but one should immediately re-lift the leg after.

Jumping in place or springing from a raised surface, in sets of 30. Heel raises - rising on tip-toe and lowering - are good substitutes for jumping if fragile bones can’t bear the jarring.

Three to five minutes of a hip strengthener called Monster Walk, in which patients slightly bend their knees and sidestep, with an elastic band joining the lower thighs or ankles so they have to push against its resistance.

He also suggests Tai Chi because it builds strength and improves flexibility, reflex reaction time and range of motion.

SPECIAL TOOLS

Some therapists, such as Jon Hardy at Tri-Lakes Physical Therapy in Hot Springs, use a Bio-Dex Balance System, a platform with a touch screen that challenges balance under simulated real-world conditions, such as uneven pavement.

Nearby Hot Springs Village is a retirement community and Hardy estimates that half of his patients have some sort of balance problem. “Falls are significant life-changers. A fall with an injury most often results in a loss of independent living status and the ability to stay at home, instead of in a nursing home or with family members,” he says.

AGE MATTERS

In older adults, balance changes may be gradual. In Pollard’s experience, “It doesn’t happen overnight. If you don’t pay attention, it slowly creeps up on you.”

But in children and younger adults, problems can come on suddenly. According to Dornhoffer, childhood vertigo is often caused by a migraine disorder, and dizziness may be triggered by the demands of puberty. “They grow so quickly their blood volume can’t keep up with them,” he says. Sometimes symptoms are severe enough that a doctor will order an MRI to rule out serious conditions, such as a tumor.

In young or middle-aged adults, underlying infection, inflammation, the use of steroids and powerful antibiotics or activities that disturb the inner ear can play a role.

EYES VS. EARS

During the Clinton administration, Dornhoffer worked with a neuro-vestibular adaptation team to try to figure out why astronauts got sick during the first few days of a space voyage: “If your eyes say you’re going straight, and your [inner] ears say you’re going up, like zero gravity,” you’re in trouble, he says.

“After three days, the astronauts stop getting sick. We’re not sure what the brain is doing to compensate. Some folks think it’s learning to ignore the ear.”

On Earth, nausea that’s caused by a similar sort of vestibular mismatch can persist for days, or in rare cases, much longer, after a cruise. “They call it disembarkment syndrome .… It can be very frustrating. There is no cure except to go and live permanently on a cruise ship,” Dornhoffer says.

“Our eyes and ears are tightly connected. Our eyes and ears should give the same information.”

For this reason, Dornhoffer cautions that walking on a treadmill can complicate balance disorders. So, for people in danger of falling, treadmill workouts aren’t the best method.

But exercising, in general, is good and patients who avoid activity due to dizziness risk prolonging their problems.

“Go to the mall, go sightseeing. If you do not go out and do stuff, you will not get better .… You have to show your environment to your eye, the same way you have to show a computer where the mouse is,” he says.

ActiveStyle, Pages 27 on 06/10/2013