Less than a month before the oil spill in Mayflower in March, crude oil flooded a small pumping station in south Arkansas, then spilled out of a holding pond and flowed several miles along a creek bed leading to Little Cornie Bayou.

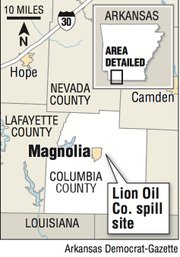

The total amount of oil released March 9 - about 5 miles east of Magnolia - by some estimates was nearly equal to the amount that spewed 20 days later from the ruptured Pegasus pipeline and threatened Lake Conway in Faulkner County.

While the March 29 spill in Mayflower led to the evacuation of 22 homes and lingering concerns about health and environmental damage, the March 9 spill was quietly cleaned up with only one resident complaint that originated more than 3 miles from the spill site.

About 10 a.m. on March 9, representatives from Lion Oil Co. contacted Larry Taylor, Columbia County’s emergency management coordinator, to tell him about an oil release at the station on County Road 25. A malfunctioning suction pump that transported crude oil from one of the company’s oil tanks to an underground transmission line had led to the oil release, company officials later reported.

Taylor went to the scene, where he found black crude covering the ground, overflowing a containment pond and moving into a creek bed on the property. The oil flowed along the creek for 3 miles, topping natural dams along the way, according to reports prepared by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“It was quite a bit of oil everywhere,” Taylor said in an interview last week.

In its initial report to the National Response Center, a federal interagency communications center that is responsible for informing various groups of an emergency, Lion Oil estimated the spill to be about 1,500 barrels.

However, after recovering more than 4,200 barrels of crude oil during its cleanup, the company modified the spill amount several days later to about 5,000 barrels, records show. A barrel contains 42 gallons.

Two days after the spill, an inspector from the Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality and Mark Hayes, an EPA on-scene coordinator, visited the site with Lion Oil officials.

Chris Voss, a water inspector for the Environmental Quality Department, wrote in a spill memorandum that Hayes informed company officials “that this was a large spill and an aggressive approach to the cleanup would need to be implemented to control the impact.”

Over the next several weeks, at least four contractors hired by the company used dams and vacuum trucks to contain and collect the spilled oil, according to EPA reports.

Taylor said the county got a light rain soon after the spill, but the oil never reached a drinking water source, which was his main public-health concern.

Keith Johnson, a spokesman for Tennessee-based Delek U.S. Holdings Inc., which owns Lion Oil, said the company had completed remediation at the site by mid-April and would “continue to monitor our equipment to the best of our ability” to prevent future spills.

Johnson said that while some estimates put the spill at more than 5,000 barrels, only 1,500 barrels entered the nearby creek. Most of the oil, he said, remained on the ground and in the containment pond at the site. He said workers at the station moved quickly to tend to the spill.

“As soon as it was discovered, we took all the steps toward controlling the release,” Johnson said.

Sandra Cawyer, the Columbia County assessor, said property values were not negatively affected by the spill. Unlike the spill in Mayflower, where crude oil flowed between houses in the Northwoods subdivision, the Lion Oil spill mainly affected agricultural land, she said.

Cawyer said her office had not received any requests for appraisal adjustments in relation to the spill, but that she would watch for any historical impact on the neighboring properties.

“Anything that can affect the value in the long term could have an effect on what the assessment would be down the road,” Cawyer said.

Lion Oil has not been issued a legal order in connection with the spill, which is still being drafted by the Department of Environmental Quality, a spokesman said. But a draft consent agreement obtained by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette through the Freedom of Information Act showed that the department was considering a few thousand dollars in fines - far less than what Exxon Mobil is expected to face in the Mayflower spill.

Katherine Benenati, a spokesman for the department, said she was not sure when the legal order in the Magnolia spill would be issued.

A spokesman for the EPA said that agency will not levy any fines against Lion Oil because enforcement activities had been handed over to the state.

About a dozen Lion Oil employees were seen working at the site during a visit by a reporter last week. The only traffic on the freshly tarred roadway leading to the station were Lion Oil vehicles and a mail truck.

About 100 yards from the roadway, several vehicles were parked next to the tank and various buildings that were flooded with oil in March.

Oil spills are not uncommon in south Arkansas, where a web of oil and gas pipelines is just a few feet beneath the surface. Every two to three months, Taylor responds to a spill on a roadway or a pipeline’s small release, he said.

Most spills of gasoline or crude oil amount to only a few gallons or barrels, according to information maintained by the Department of Environmental Quality and National Response Center.

But, Taylor said, if a pipeline ruptured in Magnolia, the biggest city in Columbia County, it would require evacuations to ensure public safety.

“We’ve got them [pipelines] running out of the city limits of Magnolia, and yes, it concerns me,” Taylor said. “It’s just a highway under there.”

Front Section, Pages 1 on 07/28/2013