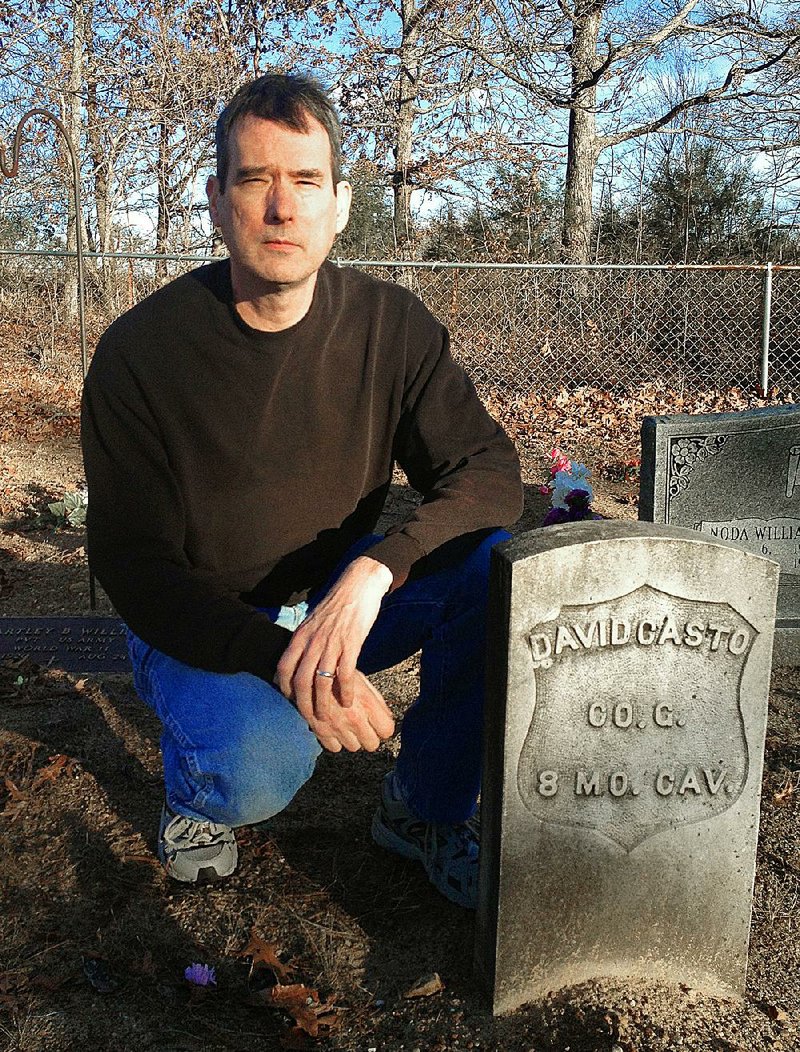

David Casto visits the tombstone with his name on it - a simple marker in Union Hill Cemetery in the far northeast corner of Pope County.

“It doesn’t bother me,” Casto says. “I’ve seen it ever since I could walk.” Any time that called for decoration, this grave had flowers on it.

Casto, 52, of Maumelle, is named for his great-grandfather. His “Grandpap” Casto stands in a family portrait taken on the farm.

The photo dates to around the time he died, 1917. He was the lean “old soldier” of the bunch, having been a Union cavalryman in his youth. His Civil War exploits were the subject of family legend.

He rode a sleek black mare, the story went, and he jumped her across a ditch to knock an enemy horseman out of the saddle.

True? Maybe, probably. But the man couldn’t write, except for his name. He left behind no diary, no letters. And nothing in his service records verifies any such deeds of valor.

The records say, “present for duty, present for duty,” the current David Casto discovered when he finally got hold of a slim bundle from the National Archives and Records Administration.

He wanted to find out more - everything more - about his blue-eyed ancestor, the one who had lied that he was 18, fudged a year, to join the Army.

“This fired my imagination,” Casto says, but he was in for a long search.

“If I had found what I wanted right away, I might have quit,” he says. Rather than amass a home office full of books and papers, “I might have stopped.”

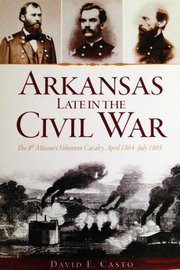

Instead, he put 16 years’ research and writing into a 126-page book: Arkansas Late in the Civil War: The 8th Missouri Volunteer Cavalry, April 1864-July 1865, new from The History Press of Charleston, S.C.

THE BETTER STORY

Working on the book aside from his regular job as a mechanic, Casto never did find all he wanted.

He is resigned that he never will. No matter what dreams a genealogist might have, not everybody’s grandpap shook hands with President Lincoln.

But he came across a story that his ancestor might have preferred that he tell anyway - about a regiment of seemingly little consequence in the war in Arkansas.

Grandpap’s regiment, the 8th Missouri, “wasn’t at the battles of Arkansas Post or Helena,” Casto writes. “It didn’t take part in the Camden Expedition.”

It wasn’t around for the action at Poison Spring, Marks Mill or Jenkins Ferry, and did not stand in the way of Maj. Gen. Sterling Price, commander of the Confederate District of Arkansas, on his raiding march to Missouri.

Charged with “cleaning out the country,” the 8th went after rebel guerrillas in a sweltering mire that Casto likens to the war in Vietnam.

They never knew by looks, he writes, “who among the local population was friendly.” Shots came at them from sources impossible to predict, infrequent but just as deadly as a musket ball at Gettysburg.

The cavalry was under equipped to the point of lacking horses. Heat, hunger, sickness and bad weather hit them worse than the human enemy.

In the end, Casto finds, the 8th did nothing decisive in Arkansas during Grandpap’s year of service, let alone important in the War Between the States. The statement is apparent truth, not a disappointment.

He cannot speak for his great-grandfather, but it’s safe to imagine the old man would answer: So what? Pay attention. This matters.

“It was important to the men who went through it,” Casto says. “Men who were killed, or wounded or captured - it was important to them, and that makes it important.”

Meaningful to him, too, because history is only partly about the past, the way he sees it. History is right now, too, and a reminder that “we make the future by living.”

In dedicating the book to his wife, Cindy, and 9-yearold daughter, Eva, he writes: “It’s all about family and future.”

PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE

The past shapes tomorrow in ways like this:

Grandpap’s story inspires Casto, who never considered himself an author, to write a book. He pieces away at it,much of this time working as a field representative for a machinery company out of Chicago.

The work sends him to Japan, where he meets Cindy, who is from China.

“I was learning Japanese in Japan,” she says. Languages appeal to her, and she teaches Chinese in Maumelle.

“I took my writing with me,” David Casto says. This was about 14 years ago, and he had the book’s introduction and first chapter to show for himself.

Anyone could have told him that part of a book is no way to capture a woman’s attention - not when she is from Shanghai, the most populous city in the world, and he is writing about things that happened more than a century ago in a rustic emptiness that was completely foreign to her.

Even so, “I thought it would impress her,” he says, “and it did.”

Everything he told her was brand new to her, she says. The part he writes about “being a little kid on a farm in Arkansas,” so different from anything she experienced growing up, made her want to hear more.

And the study of genealogy - tracking down long-lost information about a person’s ancestry - this, too, came as a new thought. Chinese families don’t have to sort through tangled lines of immigration to know their ancestors, she says. Knowing the past is a part of their heritage. How would it feel, she wondered, to have questions about your family?

“I’m really proud of David for getting his book published,” she says, having pitched in the computer skills it took to format the text. “Research and writing are not only his hobbies after work, but also his passion.”

Grandpap’s influence extends, through the book, to dark-haired daughter Eva as well. Since her dad wrote a book, and even set up at a bookstore and signed copies of it, Eva wants to write a book, too.

He won a prize for his writing - the 2012 Charles O. Durnett Award from the Arkansas Historical Association - so it’s plain to see, this sort of thing can pay off.

Eva’s work in progress, Two Weeks at Goose Manor, is about a school field trip to this place where “they find out it has ghosts and things.”

But still, she says, coming back on point to her dad being interviewed for the newspaper, “I think it’s important for kids to learn about Arkansas history.”

SOLDIER’S LOT

Arkansas Late in the Civil War is the story of what Grandpap Casto did in the war, not in specifics, but the sort of experiences that likely befell him as a member of the 8th Missouri.

“I started this research to learn what my 17-year-old ancestor did in the war. Eventually, the ‘why’ of it became equally important,” Casto says. “What drove events in Arkansas in 1864-’65?”

His great-grandfather enlisted just in time, it seems, to be guaranteed a share of frustration. In 1864, Maj. Gen. Frederick Steele cut the Department of Arkansas to half size in order to send 12,000 men from Arkansas to Louisiana.

Left behind, the 8th faced too much territory and trouble to have anything but a hard go.

One of the regiment’s worst adventures came when they were ordered to cross the White River by flatboat in the rain. Horses swimming, the men reached the far shore in the dark.

At this point, Casto writes, “General [Joseph] West lost his nerve,” fearing the enemy was at hand. He ordered the men to cross back - this time “in complete darkness in a driving rainstorm.”

The men made it, but 15 horses drowned.

There was the swamp trek in winter that Col. Washington F. Geiger described as the “most harassing, most fatiguing march ever made,” all for a job of horse- and cattle-gathering.

And almost certainly, the Civil War era’s David Casto met the war’s end by sailing tediously to New Orleans, only to discover he had been mustered out of service days before his arrival.

Family legend has it that he became so sick on the trip back to St. Louis, the end of the war nearly killed him.

But as Grandpap could have retorted, it isn’t what the regiment accomplished, or didn’t, that tells what history should make of them. It was how they stood up, how they kept going, how they took it.

“They could say they had done all that was asked of them,” Casto writes.

QUESTIONS

The author counts himself lucky. His book found a publisher, and he knows where Grandpap is buried, in Union Hill.

Other people’s great-relatives, veterans of the 8th Missouri, are apt to be among those resting under nameless stones in Little Rock National Cemetery. They may be “unknown,” he writes, but “they sleep in soldier’s graves.”

Book done, he is left to keep puzzling about the farm boy David Casto who grew up in a Union family with roots in Virginia, who stood a strapping 5 feet 8 inches, big for the time, and went to war with intents that he might or might not have felt were satisfied.

But he never forgot, and his children never forgot, and his great-grandson wrote a book about it to make sure the author’s daughter could touch the past.

“I wish I could talk to him,” Casto says. “I’d like to ask him some questions.”

Style, Pages 50 on 07/28/2013