LITTLE ROCK — Delita Martin’s life hangs on the walls.

“I grew up in a family of artists and storytellers in Conroe, Texas,” Martin told the audience at a recent reception at Boswell Mourot Fine Art, where her current exhibit, “Piecing Together,” is showing through March 9.

It’s an apt title. Her mother, grandmother, great-grandmother and two of her sisters were quilters, her father was a painter and another sister was a painter and a writer.

“This is what we did every day,” Martin says in a conversation a few days later. “I can’t remember when I wasn’t drawing; I was born into an art school and my dad was my first teacher.”

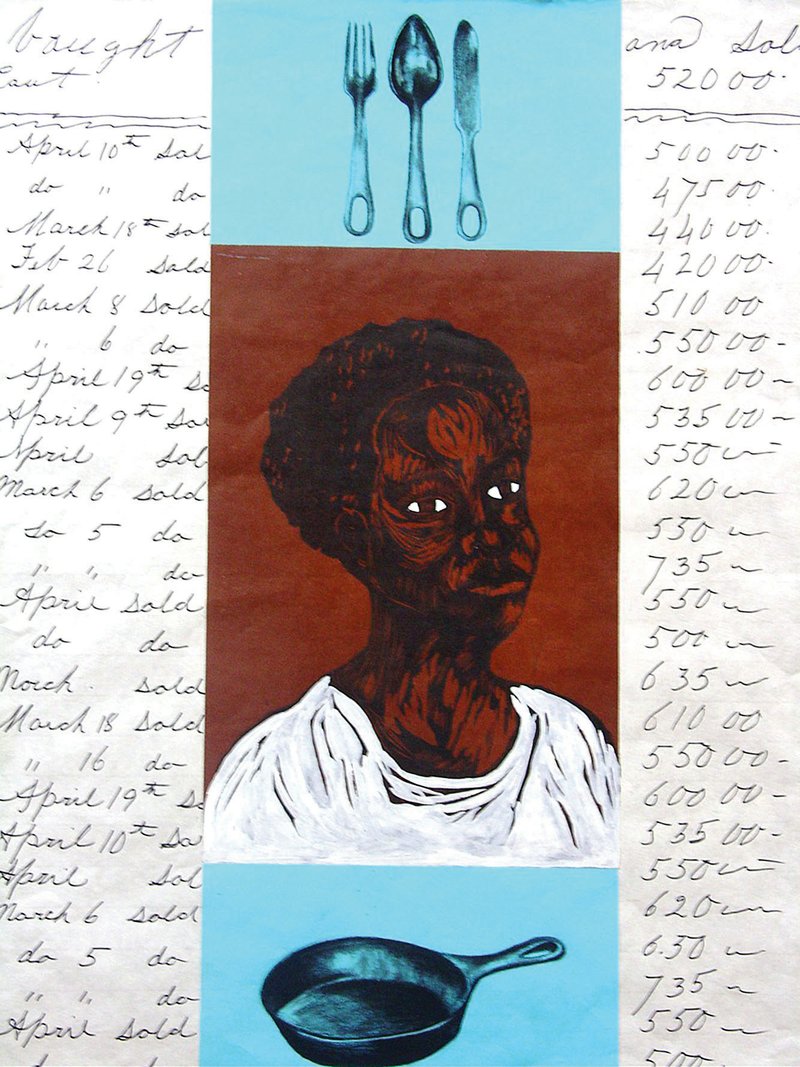

Her relatives tell “great family stories” that Martin says she draws upon when she creates art … print works that are pieced together from memories, research into the feminine archetype in cultures around the world and, particularly, the African diaspora. Her art is also literally pieced together, combining drawing, painting, etching, hand lettering and more. She prints each work 10 to 15 times before getting the final result.

Martin, 40, draws inspiration from her family and rural upbringing as she explores her identity “as an artist and an African-American woman.”

“Being a wife and mother has challenged me to have a greater insight into my family and into myself as an artist. To be able to record my history, visually, is very important to me, so I can pass it on to my son.”

She does share stories of her childhood with her son, Caleb: “We would wake up in the morning and soon were out the door. We used to play in the fields, the farm; we had animals and horses. Sometimes we didn’t get back home until dinner. I don’t think my son grasps the total freedom, the safety of community I had as a child.”

Amelia Taylor, Martin’s great-great grandmother, was a slave.

“I went through our family, talking to those who knew her, and they had amazing stories about her life and that inspired my research into the imagery of African-Americans. It was a spark for my identity, my culture.” These women, she says, are “foundations of the community.” Those lives manifest in the art, such as written descriptions of life and living from letters, food lists and historical records.

Viewers will see safety pins, Mason jars and other items of daily life in the art that relate to the women depicted and to Martin’s own family.

“My grandmother saved everything … old perfume bottles, wooden spools without thread … and kept it all in Mason jars,” she says. “She had safety pins pinned to her housecoat. She would get the jars out, spread the contents on the bed and tell me stories about each one of those things. A spool brought the memory of a particular quilt. We used to sit outside in the evening and she’d have her lanterns out. She had a bucket with scraps of fabric she didn’t use for quilting and would set that on fire to create smoke to keep mosquitoes away. I learned to associate these items with people, places, things … and they became a vocabulary in my art.”

In her Little Rock studio, Martin says, she is “surrounded by pictures of my family and people I don’t know … I like to collect old photos. For me, creating art is intuitive. I like the spirituality of it. I don’t like going into the studio with a plan. I can bring a part of myself to it that sometimes goes beyond anything I’ve anticipated.”

As a child, her path as an artist seemed set; it was one her father, who became a plumber after college to support his family, did not get to choose.

“He wanted to help me have an opportunity to have an art career,” Martin says. When she was age 12, her father arranged to have John Biggers, an influential painter who established the art department at his alma mater, Texas Southern University, to look at her work.

“Dr. Biggers noted that I had already developed my style, but more importantly, he understood what I was seeing,” Martin says. “I grew up in a mostly white area. In school, I was being told I needed to reconsider my subjects, my colors. I was on top of the world after that meeting.”

He also gave Martin some advice: “Young lady, do not ever miss an opportunity to uplift your people in your work.” She later enrolled at TSU and returned in her early 30s to study printmaking.

“I was inspired by Dr. Biggers to become a print maker,” she says. “I was at Texas Southern in the printmaking room, watching him make lithographs. It was like magic to me, it was intuitive, spiritual. I knew I wanted to do this, so I went back to school.” She also has a master’s degree in printmaking from Purdue University.

A former printmaking and drawing teacher at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Martin says art for her is “waking up and living.”

More than two decades ago, Biggers urged Martin to use her art to “uplift your people.”

But as “Piecing Together” shows, she has uplifted us all.

“Piecing Together: Works by Delita Martin,” through March 9, Boswell Mourot Fine Art, 5815 Kavanaugh Blvd., Little Rock. Hours:11 a.m.-6 p.m. Monday-Friday; 11 a.m.-3 p.m. Saturday. Info: (501) 664-0030, boswellmourot.com E-mail: [email protected]

Style, Pages 29 on 02/26/2013