SEVASTOPOL, Ukraine — For a place scripted for a starring role in the end of the world, Balaklava Bay puts on a pretty face.

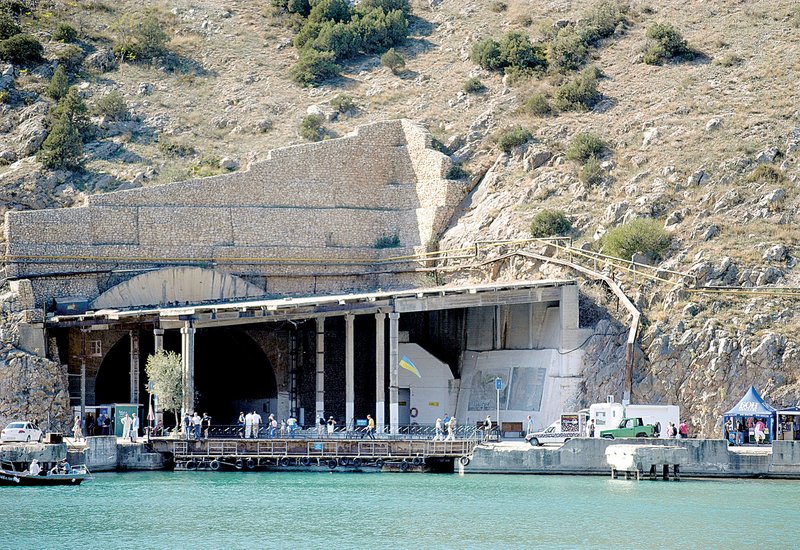

With its string of seafood restaurants and cafes along the waterfront looking out at prim sailboats and humming powerboats cutting across the water, there’s no hint of Gotterdammerung. That is, until your eye catches a dark spot on Tavros Mountain across the way. A concrete lip frames a large hole that water flows to and disappears into the dark.

From here, the Soviet Union ensured it would get its revenge from beyond the nuclear grave. In a strategy insane and irrefutable, the United States and Soviet Union each engaged in a policy of mutual assured destruction, known by the acronym MAD. No matter how many missiles and bombs rained down on one country, enough of the other’s arsenal would survive to make sure the perpetrator didn’t escape unscathed. The base at Balaklava was designed to withstand a nuclear attack and then unleash a storm of missiles at the United States.

But the Cold War ended not with Armageddon’s nuclear bang, but communism’s exhausted whimper. The Soviet Union spun apart, leaving one of the key “Russian” military bases in the world deep inside another country, Ukraine. Though Russia has negotiated a deal with Ukraine to keep a base in nearby Sevastopol, the submarines sheltered in Balaklava Bay were sent home, their nuclear missiles dismantled or taken back to Russian soil. With the Soviets gone, the base was abandoned, its rooms looted. The Ukrainian government in 2003 ordered the military to take over the facility with the plan of converting it to a museum. Balaklava’s doomsday base would finish its life as an attraction for the growing number of Western tourists who are coming to the Black Sea region on cruises and vacations.

I arrived on an early October afternoon on a tour bus from the nearby cruise ship stop of Yalta. If an American strolled along Balaklava Bay with a camera around his neck a generation or so ago, it would likely have led to a one-way ticket to the KGB’s Lubyanka Prison in Moscow. Until 1995, Balaklava Bay and most of the area around the city of Sevastopol was a closed city. No foreigners were allowed to visit. Russians had to apply ahead of time for special clearance. If their need was found less than compelling, they were ordered to stay away.

Today, there is no such problem. Take all the pictures you like, our tour guides told us. And, please, invite more Americans to come and do the same. A little strolling, a little shopping, a little snacking and a visit to the doorstep of Armageddon.

The bay is tiny - just under a mile from the mouth of the Black Sea, flanked by high mountains on each side. A 15th-century Genovese fort sits atop one hill, a remnant of earlier conflicts in the region. Balaklava’s subtropical climate makes it an excellent spot for cultivating grapes that are turned into a sparkling white wine. The vines grow in the nearby “Valley of Death” made famous by poet Alfred Lord Tennyson in his The Charge of the Light Brigade, about a suicidal cavalry attack during the Crimean War between Britain and Russia in 1854. The area was the scene of bloody fighting during World War II - more than 11,000 German soldiers are buried on the peninsula.

After lunch of local wild salmon, we took a bus to the far side of the bay. Though it was summer, we put on jackets before stepping into the dark, wet recesses of the Cold War.

In 1951, Soviet dictator Josef Stalin ordered the doomsday submarine base built, no matter the cost. He put his trusted deputy premier, Lavrenti Beria, in charge of the project. Beria at the time was the second most powerful man in Russia, in charge of everything from the Russian atomic bomb program to the secret police. Beria brought in experts who had built the Moscow subway system to carve a channel through the mountain, creating a secret link between Balaklava Bay and the Black Sea. Blast doors weighing 150 tons were placed at the ends and the channel was curved to lessen any blast effects.

Beria would not live to see the work completed. After Stalin’s death on March 5, 1953, Beria briefly served as a top leader before he was ousted, arrested for treason and shot in the basement of Lubyanka Prison, where he died Dec. 23, 1953.

The base opened in 1957, and the village of Balaklava was formally annexed into the military city of Sevastopol. In “normal” times, the channel could be used to secretly armand maintain seven Soviet nuclear missile submarines at any time. The submarines would surface in the Black Sea at night and the authorities would shut off all the lights to the surrounding city. The submarine would enter Balaklava Bay and sneak into the underground channel before lights were restored. When the work was done, the submarine would wait until dark and then take the secret exit directly into the Black Sea and disappear.

But the base’s most important role would come in war. We walked along the long, wide corridors flanking the channel, where thousands of sailors and civilians would hide from nuclear bombs.The base was built to withstand a direct hit of up to 100 kilotons, the equivalent of six of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima. In the armaments room of the museum was a display of four mock nuclear warheads, along with models of the Typhoon nuclear missile submarine. The role of Balaklava was to survive that first attack, open its doors and send submarines into the Black Sea, where they would launch a retaliatory strike against the United States.

Balaklava never had a chance to play that role. Today its missiles and submarines are gone. After a decade of disuse following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Ukrainian government has been working to turn the sprawling complex into a showcase for “what if” Cold War tourism. The base has been used for art exhibitions and community events. There are plans for more exhibits on nuclear war, and hopes of bringing a decommissioned missile submarine back to the base and parking it in the channel for visitors to see.

Today most of the exhibits are in Russian or Ukrainian, but there are plans to add more English and German signs as foreign tour groups drop in more often. Eventually, there are even plans for that greatest symbol of the victory of capitalism: a gift shop.

GETTING THERE: Like most American tourists today, I visited Sevastopol as part of a cruise stop in nearby Yalta. Cunard Cruise Line offers the Balaklava Bay tour as an option on its annual “Pearls of the Black Sea” cruise. Independent travelers can reach Sevastopol by a 17-hour train from Kiev or overnight ferry from Istanbul. Americans can stay up to 90 days without a visa. The hours of the Balaklava base museum vary widely, and some independent travelers have reported finding it closed when they tried to visit. Arrange for a tour guide through your hotel. Prices vary with season and demand, but an English-speaking guide can generally be booked for $200 for four hours during the summer.

PARADES: Military parades are held May 8 on Ukraine Victory Day, marking the end of World War II, and Ukraine-Russia Navy Day (July 23).

MORE INFO: The U.S.-Ukraine Foundation represents Ukrainian tourism interests in the U.S. Check out traveltoukraine.org, usukraine.org or call (202) 223-2228.

Travel, Pages 54 on 02/17/2013