2 USS Monitor sailors to join Arlington unknowns

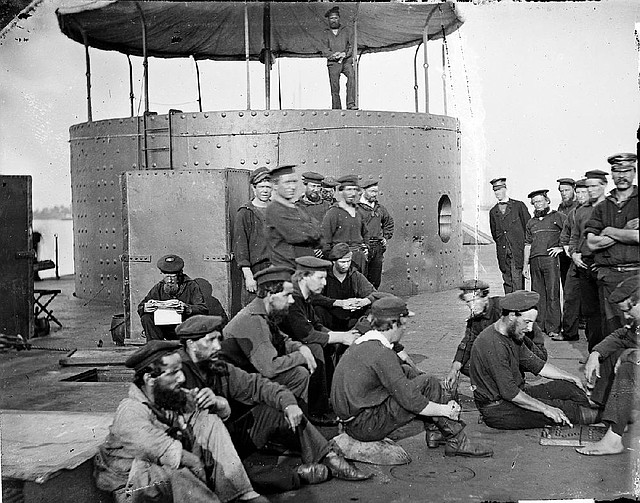

The crew of the USS Monitor sit on the deck of the ship in this undated photograph. The ship sank off the North Carolina coast on Dec. 31, 1862. The remains of two Yankee sailors found in the ship’s turret will be buried on March 8, 2013, at Arlington Cemetery. Their identifies are not known. Illustrates MONITOR-BURIAL (category a), by Michael E. Ruane, (c) The Washington Post. Moved Tuesday Feb. 12, 2013. (MUST CREDIT: Library of Congress)

Sunday, February 17, 2013

LITTLE ROCK — For 140 years, the two Yankee sailors lay entombed in the turret of the USS Monitor, doomed shipmates aboard the sunken Civil War vessel 40 fathoms down and 16 miles off Cape Hatteras.

Their remains were recovered when the turret was raised to the surface in a feat of marine archaeology and engineering in 2002.

Next month, after a decade of trying to learn their identities, the Navy plans to bury the comrades as unidentified in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors.

The funeral, scheduled for March 8, will mark 40 years of research into the Monitor by the Navy, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Va., and many other organizations.

And it will lay to rest perhaps the last of more than 600,000 soldiers, sailors and Marines who died in the longago war for the Union. The nation is commemorating the sesquicentennial of the Civil War, which ran from 1861-65.

“These may very well be the last Navy personnel from the Civil War to be buried at Arlington,” Navy Secretary Ray Mabus said in a statement. “It’s important we honor these brave men and all they represent as we reflect upon the significant role Monitor and her crew had in setting the course for our modern Navy.”

The Monitor is famous for battling the Confederate ship the CSS Virginia, formerly the USS Merrimack, on March 9, 1862, at Hampton Roads, Va., in history’s first fight betweenironclad warships.

Ten months later, the two sailors were aboard the Monitor when it sank in a gale off the North Carolina coast on Dec. 31, 1862. The ship capsized and settled on the bottom upside down.

Most of the 63 crewmen escaped. Sixteen men died, and the bodies of the other 14 were never recovered.

The two unidentified men - an older sailor, about 35, who walked with a limp, wore a gold ring and always had a pipe clenched between his teeth, anda younger man, about 21, with a broken nose and mismatched shoes - were trapped in the turret.

More than a century later, their almost complete skeletons were found, one on top of the other, amid the tangle of huge guns and debris inside. The turret is at the Mariners’Museum.

On March 7, representatives from the Navy and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration will escort the remains from the military’s Joint Prisoner of War Missing in Action Command in Hawaii, where the bones have undergone study, said Navy spokesman Lt. Lauryn Dempsey.

The next day, the sailors will be taken to their graves in two coffins on a horse-drawn caisson during an interment ceremony at 4 p.m.

“It’s extraordinary on a number of levels,” said David Alberg, superintendent of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Monitor Marine Sanctuary. “There’s something comforting to know that, no matter what you go through, what sacrifice you make, that nation’s promise to look after you, bring you homeand honor you, is as good 150 years later” as it is was back then.

“Here we have two men who were lost in a storm, forgotten by even many of their descendants,” he said. “But the nation’s never forgotten.”

The wreck of the Monitor was located in 1973 by a Duke University research ship in the stormy region called “the graveyard of the Atlantic.”

The study of the bones yielded DNA but few other clues to the men’s identities. It learned of the younger man’s broken nose and indications of a limp in the older man, the ring on a finger of his right hand and a groove in his front teeth where he bit down on his pipe.

The identities of all the other lost Monitor sailors are known, and many crew members are depicted in old photographs, including a famous series taken on the ship by photographer James F. Gibson in July 1862.

But it was not known which identities go with the recovered remains.

Last year, at the Navy Memorial in Washington, experts from Louisiana State University displayed clay facial reconstructions of the two men, based on models of their skulls.

Experts hoped the clay images might, through public exposure, provide leads to the men’s identities.

Officials noted a strong resemblance between the reconstructed face of the older sailor and that of the Monitor’sWelsh-born first-class fireman, Robert Williams, 30.

In two of Gibson’s pictures, Williams appears in a cap and mustache, standing with his arms folded. He is surrounded by other members of the crew, who lounge on the deck, playing checkers and smoking pipes.

But investigators could come up with nothing more definitive, and the sailors must now go to their graves unidentified.

Officials said the case will remain open, should further information be discovered.

Front Section, Pages 9 on 02/17/2013