His cousin slain at 14, boy forever changed

Emmett Till’s kin to speak in NLR

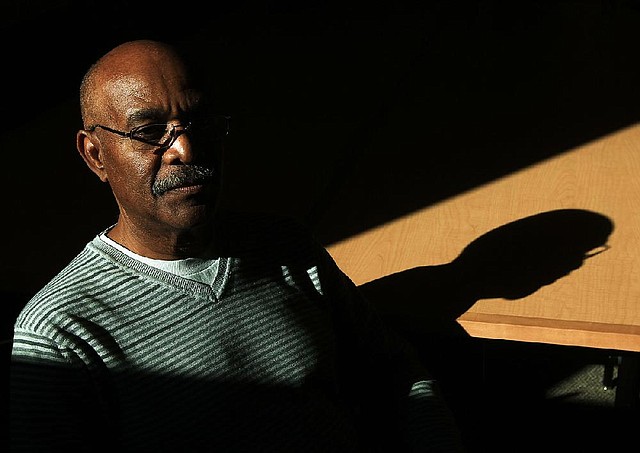

Simeon Wright, now 70, was 12 when his cousin Emmett Till was killed while visiting him in Mississippi.

Friday, February 1, 2013

LITTLE ROCK — Simeon Wright didn’t get to attend his 14-year-old cousin’s funeral in Chicago.

It was September 1955, and Simeon had to stay in Mississippi for the trial of the two white men accused of killing Emmett Till.

Simeon, then 12, knew his cousin had died a horrible death. But it wasn’t until he saw a photo of Emmett’s body in JET magazine that he realized the depth of the hatred behind his cousin’s murder.

As he stared at the picture of Emmett’s bloated and disfigured body, Simeon finally understood that the color of someone’s skin - even that of a 14-year-old boy - could provoke unspeakable violence.

It was a defining moment in Simeon’s life.

For the thousands of Americans who also saw that photo, Emmett’s slaying became a pivotal event during the formative days of the civil-rights movement. Even some white segregationists were appalled.

“When people saw that picture, it changed their hearts, their minds,” says Simeon, now 70. “They were all right with segregation, but to see the hatred that fueled it ...”

The photos of Emmett’s body were published at the insistence of his mother, Mamie Till Bradley.

Those photos and copies of JET magazine are now on exhibit at the Laman Library in North Little Rock.

The exhibit - For All the World to See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights - shows how the media helped transform the civil rights movement by making Americans look at the reality of racial bias and quotes Bradley’s words.

“I couldn’t bear the thought of people being horrified by the sight of my son. But on the other hand, I felt the alternative was even worse. After all, we had averted our eyes for far too long, turning away from the ugly reality facing us as a nation. Let the world see what I’ve seen.” - Mamie Till Bradley

At 14, Emmett was a confident boy who loved to make people laugh. He grew up in Chicago, supported by a single mother and surrounded by extended family.

Still, in August 1955, he couldn’t wait to visit his relatives in the Mississippi Delta.

Mamie warned her son that things were different down South, that he would have to watch his mouth and mind his manners when he encountered white people.

Emmett listened but didn’t really understand, says Simeon, who well remembers the day his cousin arrived for that summer visit, wearing both an excited grin and a silver ring that had belonged to his deceased father, Louis Till.

It was cotton-picking season, but the boys managed to squeeze in hours of fun when they weren’t in the fields.

One afternoon, Simeon, Emmett and the other boys went to a grocery store in Money, a small community a few miles from the Wrights’ home. The store, owned by Roy Bryant, was being run that day by Bryant’s wife, Carolyn.

Maybe Emmett wanted to make his cousins laugh. Maybe he was showing off. To this day, Simeon still doesn’t know what motivated Emmett to do what he did.

But as the boys prepared to leave, Emmett wolf-whistled at Carolyn Bryant.

Simeon and the other cousins panicked. They piled into the car and tried to explain to Emmett that in the Jim Crow South, you didn’t even look at a white woman.

Their fear soon proved contagious. Emmett became frightened and begged them not to tell any of the adults what he’d done, Simeon says.

“He was having a wonderful time. We didn’t want to spoil it.”

And, he adds, Emmett was worried that Simeon’s father, Moses Wright, would send Emmett back to Chicago early to keep the teenager safe from retaliation.

So for three days, the boys held their silence.

But in the early morning hours of Aug. 28, 1955, heavy footsteps and unfamiliar male voices in the Wright home woke up Simeon and Emmett, who were sharing a bed in one of the bedrooms.

“We’re looking for the fat boy from Chicago,” one of the men told Moses Wright.

At first, Simeon thought something bad must have happened in Chicago, that the two men had come to tell Emmett he had to go back.

Then he heard his mother pleading and crying, offering the men money if they would just leave.

One of the men was Roy Bryant. The other was Bryant’s half-brother, J.W. Milam.

Bryant seemed to waver when offered money, Simeon recalls. But Milam remained unmoved, angrily telling Emmett to hurry up and get dressed.

Emmett, by now apprehensive, hastily complied. He left the bedroom without saying a word.

Milam told the Wrights that he and Bryant were going to whip Emmett but would bring him back home afterward.

For four long hours, Simeon lay in bed, listening to cars pass by and wondering if his cousin was in one of them.

But when morning arrived with no sign of Emmett, the Wrights knew: He wasn’t coming back.

The body pulled from the Tallahatchie River three days later was so disfigured that the sheriff had to rely on a ring found on the victim’s finger for identification.

Simeon was present when the sheriff pulled out the ring and asked Moses Wright to identify it.

The ring was silver, bearing the engraved initials “L.T.”

“That’s Bobo’s ring!” Simeon blurted.

Emmett, who often went by the nickname “Bobo,” had been wearing the ring when he arrived in Mississippi. He even let Simeon wear it for a few days, despite the fact that it was too big for the younger, slimmer boy.

The sheriff ordered that Emmett’s body be placed in a sealed casket and buried in Mississippi.

But Mamie Till Bradley fought that order and managed to get her son back to Chicago for a service and burial. Thousands of people stood in line, waiting to view his mutilated body.

On Sept. 23, 1955, Milam and Bryant were acquitted in a jury trial, but they later confessed to the murder in Look magazine.

Moses Wright testified at the trial. Then he packed up Simeon and moved to Chicago, knowing his family would never again live in Mississippi.

It’s been nearly 58 years since Simeon left the South.

But Thursday, he stood next to the portion of the Laman exhibit that features his cousin and recalled vividly the events of that summer and how they destroyed the innocence he had managed to hold onto in spite of segregation.

Even now, the scent of honeysuckle takes him back to the long, hot days of berry picking, working the cotton fields and the two weeks he spent with his big-city cousin, the boy who wanted to make people laugh.

Simeon Wright will speak at 6:30 p.m. tonight at the Laman Library during a reception for the official opening of the exhibit.

Arkansas, Pages 11 on 02/01/2013