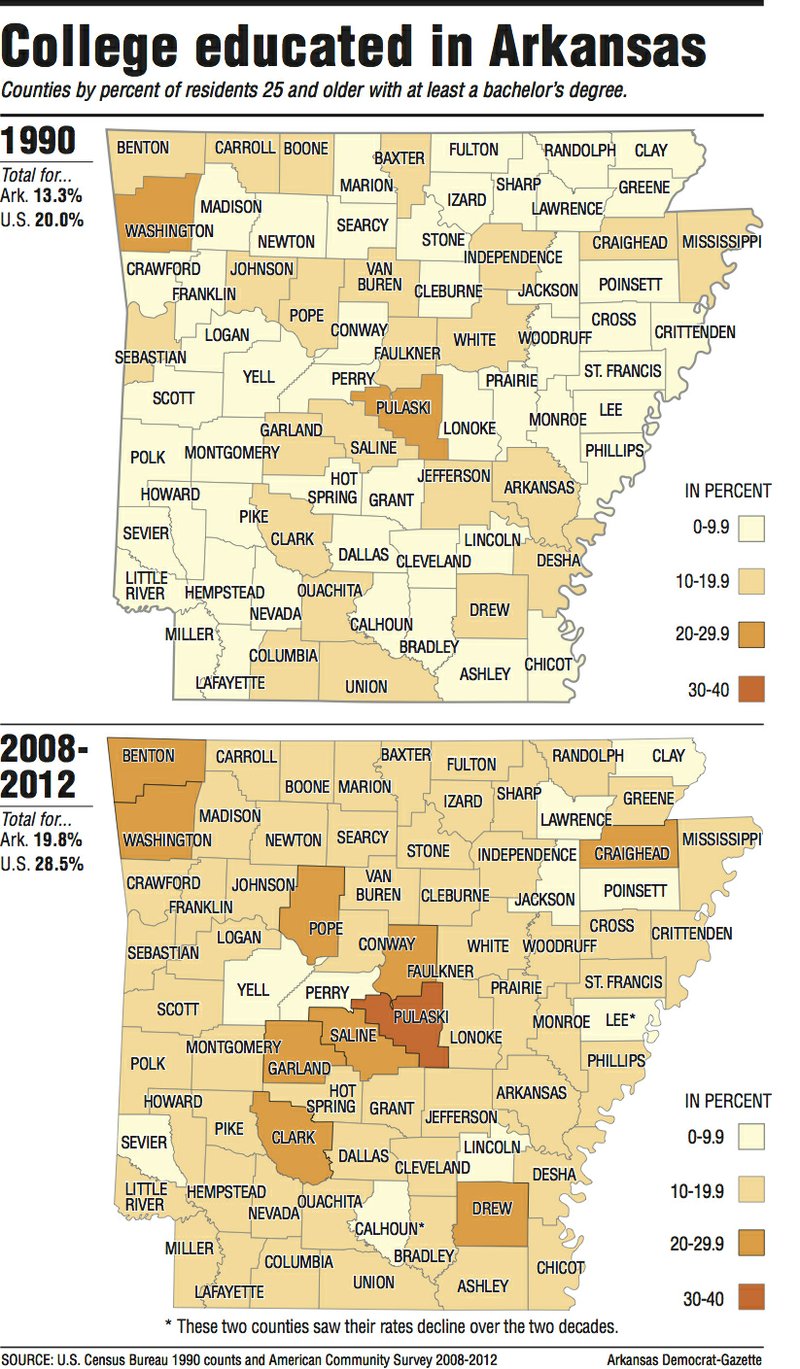

More Arkansans hold four-year college degrees than 20 years ago, but new census numbers show that only small pockets of the state have made significant strides in attracting and keeping better-educated residents.

Since 1990, most counties have seen only modest increases in their portion of residents with at least a bachelor’s degree. Indeed, some areas are worse off now than they were two decades ago, census numbers show.

State leaders and economists say the figures illuminate a divide that’s occurred across the country. Flourishing metropolitan areas have attracted the bulk of the college-educated workforce, while rural areas have struggled to attract those with four-year degrees.

In Arkansas, the central and northwest regions benefited most from the gains,helping to nudge up the statewide rate of those who hold bachelor’s degrees or higher.

In the latest figures collected between 2008 and 2012, about 1 in 5 Arkansans 25 or older have at least bachelor’s degrees. In 1990, it was about 1 in 8.

Shane Broadway, the director of the Arkansas Department of Higher Education, said it’s promising to see the figures improve, but the state still ranks near the bottom nationally - 49th,above West Virginia - in college-educated residents.

“We’re still at the back of the pack,” Broadway said. “We’ve made some strides, but [other states] are doing the same.”

All states have higher rates of college graduates now than they did in 1990. Then, college-educated residents made up less than 20 percent of the 25-and-older populations in the majority of states. Now,11 states have 30 percent or more, and most states have at least 25 percent.

But Arkansas has struggled to keep up, posting a rate of about 20 percent, according to the latest estimates. That’s lower than Puerto Rico.

The state’s ranking remains low largely because only a handful of counties meet or exceed the state average and only one - Pulaski County - surpasses the national average of 28.5 percent, the latest census figures show.

Broadway said the low numbers of college graduates in so many counties illustrate a challenge for his department that he talks about most days. Too many students from rural areas aren’t pursuing bachelor’s degrees, and those who do leave to attend college aren’t returning.

“It’s the problem of rural communities everywhere,” said Kathy Deck, the director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville.

“They want to have a college-educated workforce, so they need jobs that require college educations, but they can’t attract the jobs until they have the workforce,” she said.

The extent of the disparity is evident in the census figures, released in mid-December, that show the concentration of college-educated populations.

The state capital, areas around universities and colleges, and the home of Wal-Mart Stores Inc. in Benton County all have the largest share of residents with college degrees. In those areas, state government, educational institutions and corporate jobs have drawn better-educated people.

For instance, nearly 1 in 3 Pulaski County residents who are 25 or older hold a four-year college degree, according to the 2008-2012 census numbers. That ratio was closer to 1 in 5 in 1990.

Pulaski County now has one of the highest levels of degree-holders in the region, above Tulsa County, Okla.; Shelby County, Tenn., home to Memphis; and Caddo Parrish, La., home to Shreveport.

But travel eastward from Little Rock into the farmland of Lonoke, Prairie and Monroe counties and the rate falls until it bottoms out in Lee County - home to Marianna, James Beard Award-winning barbecue and one of the state’s highest unemployment rates.

There, only 1 in 16 adults 25 and older have a four-year degree.

That’s the lowest rate - 6.4 percent - in the state, even lower than it was in 1990, when 7.4 percent of the county’s adults had completed a four-year college degree.

State Rep. Reginald Murdock lives in Marianna, the county seat of Lee County.

He said he sees the problem illustrated in the census numbers firsthand with his daughter.

“My daughter, who just got her master’s degree, she’s in Little Rock. She works in Little Rock. She has no interest in coming back to the Delta. … In terms of opportunity and chance, the Delta does not provide it,” he said.

He said loss of industry - most notably the Camaco plant, formerly Douglas and Lomason, which closed in 2007 - has led to severe population decline in the county over the past few decades.

Murdock said now the county falls short on the three key things industry looks for in an area: healthcare access, quality public schools and a highly skilled, educated workforce.

Murdock, a former Lee County School Board member, said he believes that Lee County and other Arkansas Delta counties won’t see improvement in the education level of their workforces until the state makes a special effort to put more money into the region’s public school districts.

School districts in the Delta have a tough time retaining their best teachers and principals for more than just a few years, he said. And without those consistent role models, many students don’t get the kind of encouragement they need to make plans to attend college or a trade school, he said.

“When you give Lee County the same thing that you give those in Washington County and Benton County, then you have not changed the divide,” he said.

“What’s going to have to happen is a concerted effort to give the Delta attention so that we can attract and retain good teachers, we can do things with our facility, we can do the things that make the educational environment attractive,” he said.

In addition to Lee County, only one other - Calhoun - has fewer college-educated residents now than it did in 1990.

Both counties were among the bottom 20 of the 3,143 counties in the nation. Lee County was 12th from the bottom. Calhoun County was 16th lowest.

Deck said regressing education levels are “devastating” for a community’s economic prospects.

And Broadway said the numbers for Lee and Calhoun counties are a troubling sign that he believes warrants further study to determine why those communities have lost college-educated residents.

“It’s quite possible that it could signal that there’s something we need to do differently in those two counties,” he said.

The two counties were among those that benefit from the Arkansas Works Initiative’s career coach program, which places “career coaches” in schools in the state’s 21 poorest counties.

The career coaches provide free tutoring, mentoring and guidance on how to pay for college for students in the eighth through 12th grades. The program is funded by Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, administered through the Arkansas Department of Workforce Services.

Since the placement of the first career coaches in 2010, other areas of the state have added them, including three Little Rock high schools that added them through a grant from the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation.

Broadway said he sees promise in taking the program statewide.

“We’re seeing results. The challenge is going to be continuing funding that and expanding it,” he said. “If you could do it in all school districts, I think it would be beneficial because you’ve got kids in every school district who need it,” he said.

Broadway said another initiative, a “reverse-transfer” program announced last summer, is also aimed at increasing education levels across the state.

The program, known as Credit When It’s Due, will alert colleges and universities when students who transferred from another institution have earned enough credits to receive an associate’s degree.

The program, funded by a $500,000 grant from the Kresge Foundation, allows those students to transfer back those credits to the institution where they’ve met the criteria so they can be awarded the degree.

Broadway said his agency is in the first phase of the program, working to identify those students currently enrolled who qualify.

The program aims to expand to include former students who quit college with enough hours to earn an associate’s degree but weren’t in programs that offered them or didn’t know they qualified at the time, he said.

The program is one of several policy initiatives designed to meet Gov. Mike Beebe’s goal of doubling the number of degree-holders in the state by 2025.

Broadway said the program is a practical approach to increasing the number of residents with degrees because his department’s research has shown that people with two-year degrees are more likely to continue their education and earn a bachelor’s degree.

Broadway said it’s his hope that many of those who earn their degrees will stay in the state and return to their hometowns to start businesses.

“For a lot of these areas of the state, you’re not going to attract a 1,000-person plant. But I think what we need to focus on is bringing more entrepreneurs who can go back into their communities and employ five to 10 people.” Broadway said.

“You get more and more of those, and soon you’ve got 200 to 300 people employed.”

Deck said community colleges are also making a difference in improving the educational attainment rates in many of Arkansas’ counties.

But even those areas that have seen improvement shouldn’t be satisfied with the educational level of their workforces.

“We need to focus attention not just on the places that stick out to us just because they’re so dreadfully, dreadfully low,” she said.

“Even our most educated counties still usually don’t stack up to the nation,” she said.

Front Section, Pages 1 on 12/25/2013