Some underground water sources in a five-county area of south Arkansas are recovering from dangerously low levels, researchers say, but the state’s overall groundwater supply continues to diminish, posing concerns for agriculture, industry and human consumption.

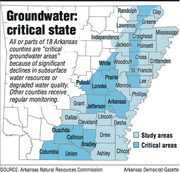

The five counties - Bradley, Calhoun, Columbia, Ouachita and Union - formed the first area of the state designated as a “critical groundwater area” in 1996, meaning that the counties had seen significant declines in groundwater resources or degradation in water quality.

Groundwater, which refers to water pumped out of the ground from rock and sand layers known as aquifers, has been the subject of study by the U.S. Geological Survey and the Arkansas Natural Resources Commission for decades.

“Continued monitoring of the Sparta Aquifer in the South Arkansas Study Area indicates that some groundwater levels in this area have stabilized or risen,” according to the “Arkansas Groundwater Protection and Management Report for 2012” published in January by the Natural Resources Commission.

But two other critical groundwater areas, encompassing all or parts of 13 counties, continue to see declines in water levels of about 1 foot per year, the study says. Much of the groundwater in these two areas comes from the Mississippi River alluvial aquifer, which lies closer to the surface than the Sparta.

Counties in the Delta that use alluvial aquifer water for crop irrigation “continue to withdraw an amount of water that is not sustainable,” the study notes.

Arkansas isn’t the only state affected by groundwater depletion. Nationally, according to a Geological Survey study by Leonard Konikow published this year, groundwater in the U.S. from 1900 to 2008 depleted by approximately 1,000 cubic kilometers. And the rate of groundwater depletion in the country has increased significantly since 1950, the Konikow study says.

“In addition to widely recognized environmental consequences, groundwater depletion also adversely impacts the long-term sustainability of groundwater supplies to help meet the Nation’s water needs,” Konikow wrote.

The possibility of a groundwater shortage in Arkansas comes as the state’s water use is projected to increase 13 percent during the next 40 years, mainly because of crop irrigation, according to a Natural Resources Commission forecast.

“This century is going to be a century where we’re going to have to find some additional sources of water and start using it more efficiently,” said Gene Sullivan, executive director of the Bayou Meto Irrigation District.

EDUCATION AND CONSERVATION

The Natural Resources Commission’s 2012 groundwater report says education, conservation efforts and a switch to water from the Ouachita River for irrigation and industrial uses contributed to the apparent reversal in water depletion in the five-county South Arkansas Study Area.

Those efforts were part of the Sparta Aquifer Recovery Project, which reduced groundwater consumption by about 50 percent, in large part by converting industrial users in Union County from groundwater to surface water sources in 2004 and 2005, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

That step has allowed rainwater to begin recharging the aquifer.

“Levels are rising at a rate that has been noted around the world,” said Todd Fugitt, geology supervisor for the groundwater section of the state Natural Resources Commission.

The commission’s groundwater report notes that “the entire study area has had an average change in groundwater levels of +8.29 feet over the last 10-year period, with Union County alone having a +26.47 change.”

The project is a “huge success story,” Fugitt said.

Union County and the Union County Water Conservation Board worked with state and federal agencies to use excess surface water from the Ouachita River, he said.

The aquifer is that county’s only source of municipal and industrial groundwater. Since development began in the 1920s, water levels had declined more than 390 feet in some areas, according to the Geological Survey. In the past decade, those levels have started coming back up, the agency’s data show.

Robert Reynolds, president of the Union County Water Conservation Board, said recovery was seen in the aquifer almost immediately after industries switched to river water.

Between October 2004 and April 2013, water levels have risen in all eight real-time wells monitored by the Geological Survey. In one well, the level has increased by almost 70 feet.

“We had a wonderful experience locally,” Reynolds said of the project. “It was much better than having someone solve the problem for us.” WELLS DRYING UP

But the recovery of that part of the aquifer won’t affect wells in other parts of the state that are on the verge of drying up, Fugitt said.

“[Water] levels are significantly reduced and approaching de-watering in some areas,” he said.

From spring 2011 to spring 2012, the U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Natural Resources Conservation Service and Arkansas Natural Resources Commission saw declines in water levels in 53 percent of the 291 Eastern Arkansas Alluvial Aquifer wells they monitor. During the past 10 years, 76 percent of 456 monitored wells showed declines.

During the same spring 2011 to spring 2012 monitoring period, 57 percent of the Sparta/Memphis Aquifer’s 178 monitored wells showed declines in water levels. The Sparta/Memphis Aquifer is a part of the same system, but north of and geologically different from the Sparta Aquifer in southern Arkansas.

The rate at which water is being pumped from aquifers is not sustainable, meaning that the water is being pumped out faster than it is being replaced by nature, Fugitt said.

About 39 percent of the water pumped from the Sparta/Memphis Aquifer cannot be replaced as quickly as it is removed, according to the Natural Resources Commission. About 41 percent of water pumped out of the Alluvial Aquifer is not sustainable, the data show.

Groundwater use in the state has somewhat leveled off during the past decade, but reached a record of nearly 8 billion gallons per day in 2010, according to the natural resources agency.

In 2009, users pumped an estimated 6 billion gallons per day from the state’s aquifers, most of it - 5.7 billion gallons per day - was taken from the Alluvial Aquifer and used for irrigation.

Users also pumped from the Sparta/Memphis Aquifer but at a much lower rate - 142 million gallons per day - and used the water primarily for municipal and industrial purposes, the data show.

For years, the Alluvial Aquifer was used for irrigation, Sullivan said. But as the Alluvial became more and more depleted, farmers started drilling into the Sparta Aquifer, which is deeper.

The Sparta /Memphis Aquifer is a drinking-water source, and as farmers began pumping from it, drinking-water supplies became threatened.

DIGGING DEEPER

Rick Bransford, a farmer in Pettus in Lonoke County, said he’s built three reservoirs and begun using tailwater (post-irrigation runoff ) recovery systems on his farm, which have helped reduce his reliance on his 31 groundwater wells. He said his wells haven’t been drawn down too much this year, but they have in the past.

“We realize it’s just a matter of time before the groundwater will be depleted,” said Bransford, who farms soybeans, cotton, corn, rice and wheat on 2,100 acres with his father. “We don’t want to pull that out faster than it can be replenished.”

Bransford said one of his neighbors hasn’t been as lucky and is trying to find a new place to drill a well.

Fugitt said that as the aquifers dry up, more money and energy must go into digging wells and pumping water from deeper and deeper underground.

“We have been in that position before, too,” Bransford said. “It’s not a good feeling.”

Attitudes about irrigation have had to change drastically in recent decades, he said. When farmers first began irrigating with groundwater in the 1960s and ’70s, they treated the resource as if it would be around forever, he said. But during the past 20 years or so, that’s no longer the case.

“People started realizing that we do have to be mindful of the resources we have,” he said. “Groundwater is a common resource that we must be sure and protect for the common good.” HOPE IN 2 PROJECTS

Several efforts, including an update to the state’s water plan, aim to replicate the success of the Sparta Aquifer recovery program elsewhere in Arkansas.

Two diversion projects that have been worked on for generations have a finish line in sight. If these projects come to fruition, Fugitt believes they could allow eastern Arkansas aquifer pumping to return to sustainable levels for the first time since 1980.

On June 20, 2016, the Grand Prairie Demonstration Project anticipates it will be pumping water from the White River to area farms for the first time. This, paired with completion of two Bayou Meto Project pumping stations this fall, could be “the answer” to groundwater depletion, Fugitt said.

This is big, he said, because he’s seen the diversion projects buried and resurrected over and over.

“We’re out of water. It’s just that simple,” said Dennis Carman, chief engineer and director of the White River Irrigation District.

The $400 million project hasn’t run into much opposition in recent years, he said. In the past, some worried about the environmental impact of pumping water from the river. But Carman said very few are against the project today.

Sullivan, executive director of the Bayou Meto Irrigation District, has been working on a similar project. He said his $700 million project was first authorized by Congress in 1950, but it lost that authorization in the 1980s. It was reauthorized in 1996.

“Water is being depleted at an alarming rate,” Sullivan said of his area. “The only way to really solve it was to divert some river water into the basin.”

Two pumping plants should be complete in the fall, Sullivan said. Water will be taken from the river and travel in a system of canals to 300,000 acres of farmland, he said.

“We’ve been very fortunate,” he said. “We’ve had good support.”

Additionally, the new state water plan, which got the official go-ahead in 2012, aims to address how to better use all of the state’s water in a way that is sustainable. The goal is for the plan to be completed by the end of 2014.

It’s been more than 20 years since the last update to the water plan. Updates can only be undertaken with state funding, Fugitt said.

The plan will forecast water use and demand, examine water availability and develop potential solutions to resolve shortfalls between supply and demand, according to a water-plan newsletter.

Fugitt said it is possible for the state’s aquifers to recover. But because there probably has been some compaction in the aquifers, he said it is not possible for them to fully recover to their original water levels.

Front Section, Pages 1 on 08/18/2013