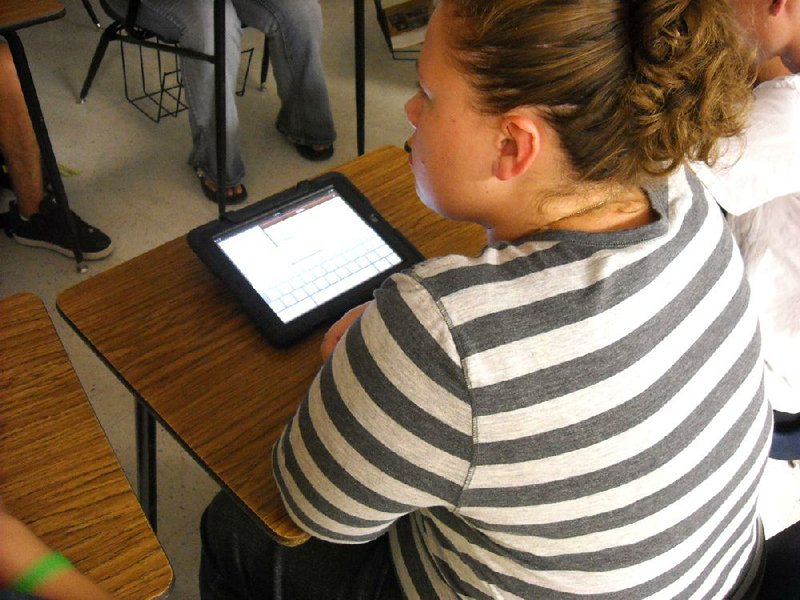

LEAD HILL — Seven students gathered in a circle in Linette Ribando’s Advanced Placement English class last week, tapping words into the iPad tablets in front of them.

The students, like the rest of their classmates in the Lead Hill High School junior and senior classes, started using the mobile devices in their classes the day before.

“The first word is diction. D-I-C-T-I-O-N,” Ribando said, directing the class to find the definition of the word.

“Word choice is the big thing you are looking for,” she said, as the students searched Google. “Raise your hand if you have it, please.”

A lesson such as this didn’texist in Lead Hill before Aug. 27, the sixth day of classes in the tiny school district on the shores of Bull Shoals Lake in northern Boone County.

The district, in an effortto recruit and retain students for the 2012-13 school year, offered the use of iPads in grades five through 12.

The district will end up distributing about 250 iPads, Lead Hill Superintendent Regina Brown said. The district owns the devices but they are registered to each student, she said.

Suzette Howerton, Lead Hill’s first-year technology coordinator, said the students will turn in their iPads at the end of the school year.

With the exception of graduating seniors, they will receive the same iPads for the 2013-14 school year and as long as they stay in the district, Howerton said.

The technology initiative is just one of the wayslocal officials and residents are rallying to save Lead Hill schools.

Under Act 60, which became law in 2004, school districts must consolidate or annex into one or more districts when their enrollment falls below 350 students for two years in a row.

District officials petitioned the Arkansas Board of Education on March 12 to annex with the Ozark Mountain School District to the south, but the proposal was defeated in a 4-4 vote.

Lead Hill’s enrollment at the end of May had dropped to 321. It was up to 363 at last count, Brown said.

The proposed merger into Ozark Mountain wasLead Hill’s last option to join a district that would keep its elementary and secondary campuses open, Brown said.

Lead Hill also looked at a merger with the nearby Bergman district, Brown said. That was the option some board members recommended.

But Bergman officials made clear that it wasn’t financially viable to keep the Lead Hill schools open if the district was to annex them, Brown said.

“Our campus and our community are one and the same,” she said. “We want to keep our community alive. If our school closes, we’re afraid we’ll die.”

So the district pivoted from a focus on joining another district to getting its enrollment over 350 and staying there, she said.

Lead Hill, population 287, and the surrounding communities served by the district rallied around the schools. Signs popped up in yards and outside businesses stating: “We Support Lead Hill School/Join Our Team” accompanied by the district’s Tiger logo.

One of those signs is propped up outside Lisa’s Lead Hill Cafe, a fixture in the town for decades.

“They’ve really done good for the kids,” said Kathy Cox, the cafe’s manager. “The community came together here to keep its school. If we lose a school, it will kill people’s value in their homes, businesses, everything.”

TECHNOLOGY OFFER

The iPad program will cost $85,000 to $95,000, Brown said.

The district is buying the iPads using money that the state distributes to districts based on the percentage of students who are living in poverty and qualify for free- and reduced-price school meals, Brown said.

The federal government sets the income qualifications for free and reduced meals at 130 percent and 180 percent of families at the poverty level, respectively.

The higher the percentage of students qualifying for the subsidized meals, the greater the amount of money the state provides the district for use in instruction and other kinds of student support.

At Lead Hill, 80 percent of students are living in poverty, as defined by federal free or reduced-price lunch programs.

Howerton said the district purchased “really good sturdy cases” to protect the tablets.

“That’s not to say they are indestructible but we did the best we could,” Howerton said.

If a student accidentally breaks his iPad or loses it, he will be issued a replacement, Howerton said. She also has a few she can lend to students while theirs are being repaired, she said.

If it is determined that a student intentionally broke the iPad, the student won’t be issued another one and will face punishment, she said.

Jim Boardman, the Arkansas Department of Education’s assistant commissioner for research and technology, said a few districts in the state have been furnishing laptop computers and iPads to students during the school day.

Lead Hill’s iPad program isn’t typical, Boardman said.

“As far as I know in Arkansas and in the country, this will be pretty unusual in that they are checking themout and taking them home,” he said.

Lead Hill High School Principal Steve Williams said the district didn’t bribe students to either attend Lead Hill or stay in the district with the offer of iPads. School officials truly think they are giving their students a technological advantage with the machines.

“I think we’re just really getting a jump on what’s happening in the future,” he said. “When they graduate from here and they can manipulate this particular piece of machinery ... that’s what the job market is all about.”

The students can take the devices home, and there are several ways the district will be able to manage the content available on each device, she said.

Each teacher has access to a program that will allow control of which websites are available in their classrooms, she said. Howerton also has a tracking program to monitor each unit for inappropriate material.

Also, students won’t be able to access the Internet if they don’t have Wi-Fi access at home, she said. But if a student does have wireless access and visits a website inappropriate for his age, the monitoring program will send her a “red flag,” she said.

The idea is for the students to do homework on the devices, she said, so they will download textbook chapters and lessons.

The juniors and seniors took to their iPads almost immediately, Williams said.

Although a technical glitch prevented them from downloading applications, they began using them the first day they got them, he said.

By the second day, some teachers, such as Ribando, had integrated them into their lessons.

“If you watch a 15- or 16-year-old kid ... [a mobile device] is like their lifeblood,” Williams said. “I’m thinking they are going to treat these a lot better than books. Thelarge majority are really going to take care of them.”

Austin Young, a senior at Lead Hill, said it is “awesome” having an iPad.

“They’re extremely convenient,” Young said. “We don’t have to carry around 50 pounds of books every day.”

Williams said he watched several high school students look up information on the countries of new foreign-exchange students.

The high school has about a dozen exchange students this year and that’s an increase from the past, Williams said.

Reaching out to agencies who supply exchange students is another strategy to increase enrollment. Overthe summer, school leaders identified families willing to host such students.

Lead Hill is using two agencies: Cultural Academic Student Exchange, a Middletown, N.J., company; and Ayusa Global Youth Exchange in San Francisco.

“People were looking for whatever we could find to boost enrollment,” Williams said.

NOT GOING AWAY

Lead Hill has the claim to be the oldest settled community in Boone County, according to The History of Boone County, Arkansas.

The 1998 book, written by Roger V. Logan Jr. and published by the Boone County Historical and Railroad Society, describes some of the major events in the town’s history, including the forced relocation of more than 100 businesses and residences from 1949-52.

The buildings needed to be moved because of the construction of Bull Shoals Dam, which impounded the White River and was completed in 1951.

Lead Hill was a thriving community 100 years ago, according to Logan’s book. In 1913, it reported a hotel, several groceries and general stores, a barbershop, doctor’s office and flour and woolen mills.

By the 1920s, communities around the area with names such as Sunset, Vinington and Chaney were shutting down their schoolhouses and sending their students to Lead Hill.

The school bell from the Lead Hill Consolidated HighSchool, which was destroyed by fire decades ago, greets visitors to the district’s current campus site.

The district is not on either of the state’s lists of academically or fiscally distressed schools, Brown said. The problem in the past few years has simply been declining enrollment, she said.

The recession hurt because parents who were commuting 20 miles to Harrison or 35 miles across the Missouri state line to Branson decided to move closer to their jobs, Brown said.

Some parents also were removing their children from the district out of the fear that it would be forced to annex and close the schools down, she said.

The district, with a staff of 73, including 32 teachers, is the area’s largest employer.

“You’d see boarded-up buildings,” if the district closed its schools, she said. “It’s just not the schoolteachers that wanted to see our school stay here. It was the parents. The parents felt that it was in their best interest for their kids to stay on campus.

“Because the parents wanted them at Lead Hill, they were going to fight for Lead Hill,” she said.

Before the state board meeting in March, the district generated 250 signatures supporting keeping a campus in Lead Hill. Mayors from Lead Hill and Diamond City lent their voice to the effort, as did some elected officials.

The show of unity wasn’t a recent phenomenon.

Several years ago, LeadHill’s taxpayers voted to pay higher property rates in support of a $2 million complex with a new gymnasium, six classrooms, a computer lab and a walking track that’s open to the community.

The district also has a new greenhouse, a new softball field and a new animalscience barn - all built with labor and materials donated by local residents.

Young, the high school senior and a lifelong lead Hill resident, and his classmate Corie Vance, said they couldn’t imagine what the town would be without its schools.

“We’ve just got to get people to come here,” said Young, who has seen three siblings graduate before him. “If we didn’t have a school we wouldn’t have a town.”

Vance said, “People have been coming here years upon years. It’s just a big part of our town.”

In the town’s small business district, Lead Hill real estate broker Jody Turner has hung a sign supporting the schools.

Turner, 39, graduated from Lead Hill High in 1991. He has several nieces, nephews and cousins still attending the schools.

“It’s foolish to shut it down,” Turner said. “It’s just the numbers. Strictly the numbers. There was talk we were going to consolidate 25 years ago when I was in school.

“We just never go away,” he said. “I just think we’re going to prove them wrong again.” To contact this reporter:

Northwest Arkansas, Pages 13 on 09/02/2012