Burned factory made clothes for Wal-Mart

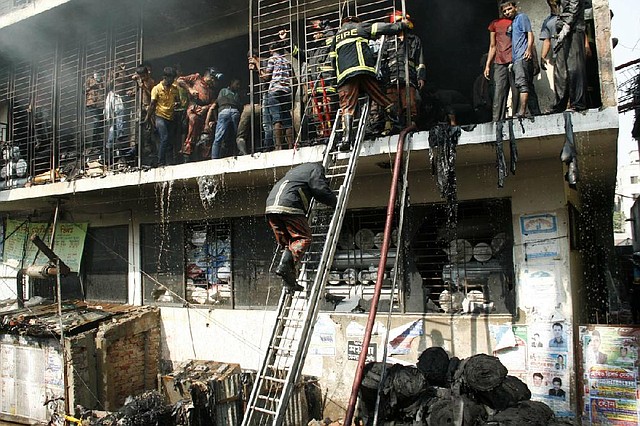

Bangladeshi firefighters and workers try to douse a fire at a garment factory Monday in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Tuesday, November 27, 2012

DHAKA, Bangladesh — The garment factory in Bangladesh where a weekend fire killed at least 112 people had been making clothes for Wal-Mart without the giant U.S. retailer’s knowledge, Wal-Mart said Monday.

In a statement, Wal-Mart said that the Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory was no longer authorized to produce merchandise for Wal-Mart, but that a supplier subcontracted work to it “in direct violation of our policies.”

“Today, we have terminated the relationship with that supplier,” America’s biggest retailer said. “The fact that this occurred is extremely troubling to us, and we will continue to work across the apparel industry to improve fire safety education and training in Bangladesh.”

Meanwhile, thousands of Bangladeshi garment workers staged angry protests Monday, demanding justice for those killed in the fire.

The protests paralyzed much of the Ashulia area, an important industrial belt north of Dhaka, the capital, as about 15,000 Bangladeshi workers blocked roads, prompting about 200 factories to close for the day.

A second garment factory in a different part of Dhaka was engulfed in flames Monday morning. By afternoon, the second fire was under control, with no casualties reported.

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina offered prayers and sympathy for the families of those who died in the weekend fire as her Cabinet declared that today would be a day of national mourning. At the same time, she voiced suspicions that the fires were arsons intended to undermine the country’s garment industry. Without presenting any evidence of arson, she called for vigilance against sabotage.

She said two workers were arrested over the weekend after attempting to set fire to another factory in the Dhaka area.

Wal-Mart did not say why it dropped the Tazreen factory. But in its 2012 Global Responsibility report, Wal-Mart said it stopped working with 49 factories in Bangladesh in 2011 because of fire safety issues. And online records appear to indicate the Tazreen factory was given a “high risk” safety rating after an inspection in May 2011 and a “medium risk” rating in August 2011.

The fire ranks as one of Bangladesh’s worst industrial accidents. Witnesses described a desperate scene, as workers leapt from the upper floors of the factory, trying to land on nearby rooftops to escape the smoke and flames. Others suffocated inside the factory building, as the blaze apparently rendered stairwells impassable.

“Managers told us, ‘Nothing happened. The fire alarm had just gone out of order. Go back to work,’” Mohammad Ripu said. “But we quickly understood that there was a fire. As we again ran for the exit point we found it locked from outside, and it was too late.”

Ripu said he jumped from a second-floor window and suffered minor injuries.

Another worker, Yeamin, who uses only one name, said fire extinguishers in the factory didn’t work, and “were meant just to impress the buyers or authority.”

TV footage showed a team of investigators finding some unused fire extinguishers inside the factory.

Kalpona Akter, a Bangladeshi labor leader, said she toured the factory after the fire was extinguished and found labels for a variety of global retailers, including Faded Glory, a brand she said was manufactured for Wal-Mart. Akter said she also found labels for brands sold at leading European retailers.

“These international, Western brands have a lot of responsibility for these fire issues,” said Akter, the executive director of the Bangladesh Center for Worker Solidarity.

Bangladesh is a garment powerhouse, with more than $18 billion a year in exports, ranking second behind China. More than 3 million workers are employed in the country’s 4,500 garment factories, most of them women. The industry has become an essential engine for the domestic economy and a critical source of foreign currency that helps the government pay for imported oil.

But Bangladesh’s garment industry has also attracted rising international and domestic criticism over a poor fire safety record, desperately low wages and policies that restrict labor organizing inside factories.

Information for this article was contributed by Julfikar Ali Manik and Jim Yardley of The New York Times and by Farid Hossain, Julhas Alam and Al Emrun Garjan of The Associated Press.

Front Section, Pages 4 on 11/27/2012