LITTLE ROCK — First, there were the cave drawings, those rudimentary scrawlings on stone walls depicting tales of hunts and other conquests. Then fast forward to ancient Greek society where they emblazoned urns and painted murals, conveying everything from the first Olympic victories to the tragic love affairs of gods and mortals.

In a way, these art forms could be considered the world’s first comic books. That’s right, comics, those colorfully covered, graphic booklets filled with exceptionally anatomically correct characters that many a boy scrimped and saved for and hoarded like treasure.

Many carried their love of comics into adulthood as their tastes evolved with the genre. A few even managed to turn their affinity into paying hobbies. A handful of those folks live in and around central Arkansas.

The two comic-book creators who are good examples of the evolution of the medium are Dusty Higgins, creator of Pinocchio, Vampire Slayer, and Stu Berryhill who inks Man of God.

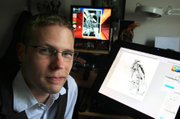

Democrat-Gazette graphic designer Higgins and former reporter Van Jensen’s work features the wooden puppet of fairy tale legend using his nose to stake vampires - before they can feast on mankind.

Man of God is a darkly semi-religious serial created by Craig Partin and inked - the term used to describe one stage of the drawing process - by Berryhill, an endocrine researcher at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. In this comic, the main character,John Morris, is burned beyond recognition in a mysterious church fire. Seemingly dead, he rises again and seems cursed with the ability to see the sins of others before doling out preternatural punishment.

Higgins, who says “I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t drawing,” reveals that Pinocchio, Vampire Slayer was born from one of his doodles.

“A lot of times when I’ve got downtime, I’ll sit and just draw, to sort of warm up or kind of learn new things - teach myself stuff,” he says. “I was messing around one day and I sketched Pinocchio and a police officer was questioning him and he was lying .... His nose comes out and he accidentally stabs the police officer. Well, that seemed a little inappropriate but I think at some point, just seeing him accidentally stabbing somebody in the chest, I thought hey, that would really work with vampires. So that was kind of the genesis of the idea.

“After that it kind of hung around in my head for about a year before I started talking to Van about it. I knew he was interested in writing comic books. I had tried to write the comic but I got through a few pages before I thought ‘This is gonna take forever.’ I told him my overall idea of where I thought it would go and he sort of ran with it. Then he had his ideas and I had mine and we bounced off each other.”

Berryhill, a U.S. Navy veteran, has spent so much time visiting The Comic Book Store in Little Rock over the last three decades that he’s practically an employee. In fact, store owner Michael Tierney (who also owns Collector’s Edition in North Little Rock), doesn’t even call him Stu. He calls him Buck, a nickname bestowed years ago.

“Before I could write, I was drawing,” Berryhill said on a Saturday afternoon while sitting behind The Comic Book Store counter as Tierney and a store manager worked and patrons shopped. “I remember my first drawings were of a T. rex with wheels.”

Berryhill says he really got hooked on comics as a boy in the 1980s after an uncle gave him several from the 1960s.

“I just got sucked in,” he says. “Of course, it took me 25 years to finally get off my butt and do something about it.”

He says he met Partin in 2005 via an online chat room for comic-book lovers, which led to their first project, a cystic fibrosis fundraiser comic. They started working on Man of God in 2007. And now Berryhill says he spends about 16 to 20 hours per week on the comic he describes as “sort of like The Sopranos meets The X-Files meets Dexter.”

A love for the craft seems to be the first indicator of success. Each man was quick to note that few, if any, manage to get rich from comic books.

“If you’re doing it for money, you won’t be doing it long,” Higgins says with a chuckle.

Neither had solid sales figures. However, Berryhill noted that the second issue of Man of God was due out this month and since May, distributors have bought a little more than 6,000 copies of the first and second issue to be sold at stores around the country for $3.50 each.

As a graphic novel - in which the entire storyline is followed from beginning to end in one larger book - Higgins’ Pinocchio is pricier at $10.95 each for the first book and $14.95 for the newer ones. He says the first printing of Pinocchio came in 2009 with a press run of 5,000 copies and another 5,000 in 2010. The second, Pinocchio, Vampire Slayer and the Great Puppet Theater was released last year. And the final act, Of Wood and Blood is slated for release later this summer. All have been released by SLG Publishing.

The first comics - those featuring squeaky-clean superheroes saving the day - appeared in the 19th century, according to Randy Duncan, a Henderson State University professor who teaches a course on the medium.

“With a sequence of static images isolated in panels, comics do not truly tell a story, but rather they offer the raw materials with which the reader can engage in storytelling,” he says. “Comics are what Marshall McLuhan called a cool medium, one that does not do all the work for us,” he says of the late Canadian professor of English literature and communication theorist.

“Readers have to be actively involved in constructing the story and creating the meaning,” Duncan says. “Also, the relationship between fan culture and comics creators has long been interactive. And, of course, comics are the blending of word and picture. A blend of word and picture, interactive, and involving - these are the hallmarks of 21st-century media.”

Tierney says the books remain relevant today.

“When I first started this business 30 years ago, I met a lot of resistance,” he says. “People thought comics were bad for kids to read. Well, within a few years, I had teachers convinced that no, it’s the other way around because when you make reading fun, that’s a good thing. With comics you’re using both hemispheres of the brain at the same time. You’re using your visual side and your other side that understands the written word, teaching both hemispheres to work in tandem.”

The subject of a High Profile story in this publication in August 2009, Tierney is sort of the Arkansas Godfather of Comics. He has published several of his own graphic novels and coached countless enthusiasts looking to break into the business. Few have the wherewithal it takes, he says.

Higgins points to Little Rock husband and wife team Mitch and Elizabeth Breitweiser and says “they’re kind of like comic book royalty here.” The pair do work for Marvel Comics, the publisher behind heroes like Captain America, X-Men, Iron Man and Spider-Man.

On Berryhill’s list (he literally had a printed list) of noteworthy Arkansas names is Nate Powell, a Little Rock native and winner of the 2009 Eisner Award for best new graphic album (“It’s kind of like the Pulitzer Prize for comics,” Berryhill says). In addition to Higgins’ name, the list also included Democrat-Gazette artists John Deering and Ron Wolfe.

While these people note that the industry has been hammered by the digital age when just about everyone has easy, instant access to video games, movies and digital comics that often feature the same characters, they don’t think traditional comic books will vanish completely.

“Comics, like most media, will increasingly migrate to the screen,” Duncan says. “The savings in production and distribution cost will certainly motivate publishers to move to digital comics, but I think there will be a market for print comics if publishers want to continue to make them.

“An awful lot of comic book readers, even some of the younger ones, seem to value the materiality of the printed comic.”

Style, Pages 27 on 07/24/2012