Riding high on the real estate wave in Northwest Arkansas, John David Lindsey successfully operated multiple development companies from his sixth-floor office in north Fayetteville for years. Then the bottom fell out.

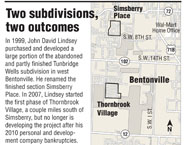

In 1999, the Tunbridge Wells subdivision in west Bentonville had been given up for dead.

Three years earlier, the original developer declared bankruptcy and abandoned the project. Grass crept over the curbs, and the neighborhood was pockmarked with vacant lots.

There were few signs of life.

Then John David Lindsey resurrected Tunbridge Wells.

Lindsey, then just 28 years old and running the Benton County office of his father’s massive Northwest Arkansas-based real estate firm, paid $18,000 to $20,000 each for 30 lots in the development and built upscale houses on them.

He renamed his portion Simsberry Place.

“He finished out part of that development, which was a big assistance to the city,” said Troy Galloway, who has been in charge of Bentonville’s planning division since 1996.

“We were fortunate,” Galloway said. “It was turning into an eyesore for the city and John David came in and basically rescued it.”

But the mercurial nature of real estate came to haunt Lindsey, whose 10-year rise to become one of the region’s major developers crumbled in the national recession that began in 2007.

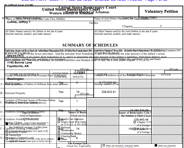

Lindsey filed for Chapter 7 personal bankruptcy in the Western District of Arkansas on Feb. 20, 2010, claiming debts of almost $169.9 million and assets of $9.99 million.

Lindsey wasn’t alone in his financial failure; the real estate bust forced many prominent developers in Northwest Arkansas to file for bankruptcy.

But his filing was the largest among those bankruptcies both in size and scope. He listed 245 local creditors, including debts totaling $120 million to 13 banks in Benton and Washington counties and three banks in Crawford and Sebastian counties.

He was forced to relinquish ownership of hundreds of houses, commercial buildings and lots stretching from Fayetteville to Bella Vista.

“John David got caught up in too much aggression in the real estate market and had never experienced the downside,” said Kirk Elsass, a senior vice president and executive broker at Lindsey & Associates, Lindsey’s father’s company and one of the state’s largest real estate firms.

Chapter 7 bankruptcy allows for liquidation of assets to satisfy a portion of outstanding debts. Lindsey filed for individual bankruptcy but marked the debt as primarily business debts.

U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Ben Barry granted Lindsey a bankruptcy discharge on March 31.

The order prohibits any attempt to collect a discharged debt, but a creditor may have the right to enforce a valid lien under certain circumstances and a debtor may voluntarily pay any debt that has been discharged.

On Sept. 9, 2010, about seven months after his personal bankruptcy, a development company owned by Lindsey — John David Lindsey Development LLC — also filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy protection, claiming up to $50 million in debt. Resolution of that bankruptcy is pending.

Trans Lease Inc., a Denver-based transportation financing business, filed a complaint in bankruptcy court against Lindsey in June 2010, claiming he misrepresented his financial standing in order to lease dump trucks.

Trans Lease argued that due to the misrepresentation, Lindsey’s debt to Trans Lease in his personal Chapter 7 was “nondischargeable.”

Barry ruled in favor of Lindsey on April 30, and Trans Lease appealed to U.S. District Court on June 1.

U.S. District Judge Jimm Larry Hendren heard oral arguments in the complaint on Jan. 3 in Fayetteville, with attorney James R. Cage, representing Trans Lease, accusing Lindsey of overstating his net worth in order to secure a loan in 2008.

“It was an intentional defrauding and certainly a reckless defrauding,” Cage told Hendren.

Lindsey’s attorney, Jill Jacoway of Fayetteville, denied all allegations of false pretenses, false representations or fraud.

“John David Lindsey is a human being,” Jacoway said. “None of us is perfect. He just tried to be as honest as he knew how to be.”

Trans Lease, one of John David Lindsey’s creditors in his personal Chapter 7 filing, is also objecting to the discharge on a separate matter: Whether the trustee in Lindsey’s bankruptcy reasonably approved a settlement of $125,000 from the J.E. Lindsey Limited Family Partnership, to resolve creditors’ claims.

Trans Lease wants to know the net worth of the J.E. Lindsey Limited Family Partnership, in which John David Lindsey of Fayetteville claimed 33 percent interest before his February 2010 personal bankruptcy.

Barry heard arguments regarding the issue on Jan. 4 and the bankruptcy case remains open.

Tim Tarvin, a professor in the University of Arkansas School of Law in Fayetteville and a frequent panelist and lecturer on bankruptcy, said the case is continuing due to objections to the “dischargeability” of Lindsey’s debts to specific creditors, in this case Trans Lease.

If Trans Lease succeeds in its complaint, its debt will not be discharged but the other debts will, Tarvin said. If the judges rule against Trans Lease, its debt will be discharged like all the others, he said.

John T. “Terry” Lee, the court-appointed trustee in Lindsey’s bankruptcy, said the funds raised from the sale of Lindsey’s assets to pay back his creditors cannot be distributed until the settlement issues have been resolved and the case closed.

Most of Lindsey’s assets were tied to real estate holdings that were foreclosed upon by his creditors, Lee said.

“Lots of lenders did not file claims or they were disallowed for some reason,” he said. “So I have no idea what banks may have recovered. Unless banks have resold what was foreclosed upon, they may have only recovered their collateral and received no monies.”

John David Lindsey, the principal broker and general manager for Lindsey & Associates, initially agreed to be interviewed for this article, then canceled less than an hour prior to the appointed time.

In a Dec. 12 e-mail, he wrote that he was “unavailable, based on attorney advice.”

Jacoway also declined requests for comment.

In a statement released when he filed the bankruptcy, Lindsey blamed the massive slowdown in real estate activity in Northwest Arkansas for his financial trouble.

Lindsey wrote that a large portion of his personal business and real estate investments were no longer viable.

“I sincerely regret any harm this situation has caused, including the financial institutions who loaned me money, the vendors who I did business with and especially my former employees and their families,” he wrote.

Jeff Collins, an economist and partner at Streetsmart Data Services NWA in Fayetteville, said Lindsey’s debt shows how far banks would go to lend him money.

“You’d have to say that he was a pretty major player in Northwest Arkansas on the residential side,” Collins said. “There was a pervasive attitude, across the lending and development communities, that Northwest Arkansas was bulletproof.

“The Lindsey name carries a lot of weight in the region,” he said. “It made them feel confident that the level [of his] borrowing was sustainable.”

COULDN’T SAY NO

Elsass, 54, who said he considers Lindsey, 40, a younger brother, said his friend simply spread himself too thin.

“Sometimes he’s done naive things,” he said. “John David’s biggest fault, other than the disastrous economy and the [housing] market ... he didn’t learn how to say no.”

Elsass and John David Lindsey were frequent business partners, and at one point the pair owned nearly 200 single-family homes in Northwest Arkansas, he said.

“People were coming to him knowing his potential to get financing,” he said. “His personality wouldn’t let him say no. Sometimes you’ve just [got] to say, ‘No, that’s not a good deal.’

“There were too many people trying to reach for some of the action.”

A prime example of a John David Lindsey project that didn’t pan out is Thornbrook Village in west Bentonville.

The Bentonville City Council approved the final plat of the first phase of development in 2007, but so far only 49 homes of a planned 149 have been built.

Six houses are still under construction, surrounded by empty acres, roads to nowhere and utility hookups for lots that were never built upon. Eight of the existing homes had “for lease” signs planted in their front yards in December.

Galloway said it’s ironic that it was Lindsey who saved a subdivision in the late 1990s and Thornbrook Village now needs to be saved.

Lindsey no longer owns any part of Thornbrook Village. It was a casualty of the bankruptcies he filed in 2010.

RISING STAR

Throughout Northwest Arkansas’ decade-long real estate surge that ended five years ago, Lindsey not only invested in residential and commercial real estate but also operated dirt excavation and transport services through various companies.

As a developer, Lindsey was involved with housing construction “from soup to nuts,” Galloway said.

Lindsey’s companies would purchase raw land, prepare it for residential or commercial use, survey it, and draw up plat maps. He and his employees would work with utility providers for establishing easements, and seek approval from city planners.

His various enterprises would pay for the construction, then sell the finished product.

In 2001, he was named to Arkansas Business’ annual list of “40 Under 40” business and political leaders younger than 40 years old across the state “who bear watching.”

Lindsey, then 31, was touted by the publication for his acumen in the development of housing projects in Bentonville, Fayetteville, Springdale and Little Rock.

Lindsey, Arkansas Business noted, was also involved with commercial developments and other business ventures, including L&E Equity Investments and Flash Farms LLC, both with Elsass, and Lindsey-Moore Investments with Pat Moore.

Rob Husong, then a senior vice president at Fayetteville-based Arvest Bank, nominated Lindsey for the “40 Under 40” list.

“He has no limits and could be one of Arkansas’ biggest leaders in the next 5-10 years,” wrote Husong, now president of Signature Bank of Arkansas.

At the time of his Chapter 7 bankruptcy, Lindsey claimed sole ownership of six companies:

• John David Lindsey Development LLC, which owned rental homes, single-family lots and raw land

• J&A Mining LLC, which owned dirt pit property

• JDL Leasing LLC, which owned equipment used in a trucking operation

• Lindsey Contracting LLC, a contracting operation that had closed

• Northwest Arkansas Truck Services LLC, a trucking operation that had closed

• Stephens Red Dirt Farm Inc., which operated a dirt pit

Lindsey also claimed ownership or interest in 24 other companies or partnerships and listed 25 co-debtors on various accounts.

He listed real property worth about $9.78 million: 63 rental houses, four lots, half interest in two other rental houses, his private home, a home awarded to his ex-wife in a divorce and some property on Salem Road in Fayetteville.

BANKS SUFFER

Kathy Deck, director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at the Sam M. Walton College of Business at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, said Lindsey and other major developers created an environment where the inventory — property for sale — outpaced potential buyers.

The situation got worse four years ago when housing prices took a nose dive, she said. Banks in Northwest Arkansas have suffered due to the Lindsey collapse, she said.

“This is an enormous amount of money in a small area,” she said. “It’s an enormous hit. It’s not that the people got off scot-free. The bankers themselves lost their jobs, particularly locally.”

Tim Yeager, an associate professor of finance and Arkansas Bankers Association Chair in Banking at UA, said local banks were thriving during the housing boom.

But the intense competition to lend money to developers on speculative projects led bankers to make increasingly risky loans, Yeager said.

“In the short term, these loans were making money,” he said. “It made perfect sense to keep leveraging the money up. As long as everything’s rising, then things can work.”

All it takes is a construction slowdown for banks to get into trouble, he said.

Deck said everyone involved “believed the good times were going to last forever.”

“The banks were making loans without considering anything but the best environment [for sales],” Deck said. “They were absolutely being as aggressive as you can imagine.”

Paul R. Bynum, owner of MountData, a real estate information company that covers Benton and Washington counties, said the height of the construction surge occurred in September 2006.

That’s when 50 percent of the 3,300 homes listed on the market were of new construction, Bynum said.

“That’s unheard of,” he said. “You know you’re in a heck of a boom market.”

In mid-December 2011, however, only 350 single family houses were listed for sale in the two counties, and of those, 10 percent were of new construction, he said.

The inventory “has definitely gone down,” he said. “So have the sales and everything else. I would surmise there’s just a ton of homes being held by the banks.”

High foreclosure rates and sinking home values — the results of the national recession — meant millions of dollars of real estate holdings went on to local banks’ balance sheets, Bynum said.

But the banks don’t want to sell in a down market, he said.

“As long as it’s not sold, it’s still a paper asset,” he said. “As long as they’re still holding it, it can still be on the books. As soon as it sells, then they have to take the loss.

“If I were a bank what would I do? You can’t dump ’em all at once because it doesn’t look good on your quarterly report.”

Many banks in the region had become “over-concentrated” in real estate lending.

“Bank performance is tied to commercial real estate,” said Yeager, a former assistant vice president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “That’s what it’s all about. How that market goes is how the banks are going.

“A lot of the [bank] shareholders lost a lot of money,” he said. “There was definite pain. A lot of pain.”

It wasn’t just the region’s financial sector that felt the sting of Lindsey’s business failures. So did his employees.

J.T. Baker was the general manager for Stephens Red Dirt Farm and Northwest Arkansas Truck Services, which both closed in December 2009.

“The landscape for development in the early 2000s, you really couldn’t go wrong,” Baker said. “It appeared to us that this would never end. If the market hadn’t turned, he would look like a genius.”

When Lindsey filed for bankruptcy two months after closing those businesses, he listed a $45,000 debt to Baker through the trucking firm. Baker said it was an unpaid bonus from 2008.

Baker, now a corporate sales manager for World Gym’s franchises in Benton and Washington counties, said Lindsey’s family kept him on the payroll through July 2010, and he still counts John David Lindsey as a friend.

“Business is business and friends are friends,” Baker said. “Business didn’t work out. It’s not going to do anything to help anybody move forward to discuss the different negative aspects.”

‘FEEDING FRENZY’

In his personal bankruptcy, Lindsey listed $159 million in unsecured debt, including $19.8 million to Liberty Bank in Springdale, $18.1 million to the Bank of Fayetteville and $11.4 million to Signature Bank.

Although Lindsey listed his debt to Liberty Bank as unsecured, Howard Hamilton, president and chief operating officer of Liberty’s Northwest Arkansas operations, said the loans were secured through Lindsey’s real estate assets.

When asked how much of the millions owed to Liberty was recouped, Hamilton responded, “That’s confidential information.”

Tarvin said the banks essentially acted as partners in Lindsey’s business ventures and thus share some responsibility for his failure.

The banks should not be seen as helpless victims, he said.

“The people that get hammered in bankruptcy are the unsecured lenders,” Tarvin said. “If you don’t get a co-signer and you didn’t get collateral [other than real estate], you basically lent unsecured money.

“There was a feeding frenzy,” he said. “The banks are victims of their own greed because they just found it irresistible. Everybody was getting a piece of the action. Until the bubble burst.”

Indeed, the majority of Lindsey’s loans were backed by local real estate that his lenders tried to reclaim after his bankruptcy. The lenders intended to take back 226 single family homes, 410 lots, three multifamily complexes and 227 acres of land.

But today most of those properties are not owned by Lindsey’s lenders. They are owned by his father.

BIRTH OF FIREBLAZE

In 2010, after John David Lindsey’s businesses went to pieces, Jim Lindsey set out to buy properties that his son had deeded back to banks in lieu of foreclosure, freeing the banks to sell those assets.

Jim Lindsey created 11 limited liability companies — all with variations of the name Fireblaze — which now altogether own about 380 parcels in Benton County and 80 in Washington County, according to those counties’ real estate tax records.

For example, Metropolitan National Bank of Little Rock sold a lot in the Peaks III subdivision in Rogers to Fireblaze IX LLC for $1.267 million on Dec. 29, 2010.

John David Lindsey owed Metropolitan more than $14.6 million when he filed Chapter 7 bankruptcy. The majority of those loans were backed by local real estate that the bank tried to reclaim.

The Fireblaze companies are organized under an umbrella firm named D&G Assets LLC. Jim Lindsey told Arkansas Business in August 2010 that D&G stands for “David and Goliath.”

Hugh Jarratt, an attorney with Lindsey Management, said Jim Lindsey met with the banks to present his plan to keep the foreclosed properties off their balance sheets.

“There were a lot of houses and real estate that were going into the bankruptcy trustee’s hands,” Jarratt said. “The banks and Mr. [Jim] Lindsey made a deal for Mr. [Jim] Lindsey to purchase those assets. Now Mr. [Jim] Lindsey owns those assets and is trying to make the best and highest use of them.

“He is just trying to make those assets work the best way he can,” he said.

Hamilton confirmed a meeting between Liberty Bank and the Lindseys to work out property acquisitions.

“That’s exactly what happened,” Hamilton said. “It was approved by the court.”

The elder Lindsey restructured the mortgages on hundreds of homes in a way that saved the banks from severe losses, Elsass said.

“Jim has tried to help stabilize our real estate market more than anybody knows or ever will know,” he said. “I know there are some people out there that feel the Lindseys ‘didn’t do me right,’ or the Lindseys ‘short-changed me.’

“Behind the scenes, I watched [the Lindseys] day and night and in the late hours to get people to try to work in a direction they could make it work,” he said. “If it was your son, what would you do? You would try to protect your son.”

Most of the Fireblaze homes are being leased, Jarratt said.

There is one notable exception. On June 16, 2010, John David Lindsey deeded his north Fayetteville home to Fireblaze Home LLC.

Washington County appraised the 4,100-square-foot home at $422,450 in 2010.

FAMOUS FATHER

John David Lindsey was born Feb. 17, 1971, to Nita and Jim, who at the time was building his real estate portfolio from his paychecks from the Minnesota Vikings of the National Football League.

Jim Lindsey, 67, played for the Vikings from 1966-72 after a standout career at UA.

He led the Razorbacks in rushing yards in 1963 and led them in receiving in 1964, when the Razorbacks went undefeated and won their only national championship in football, part of a school-record 22-game winning streak.

Since his retirement from professional football, the elder Lindsey never strayed far from the athletic program or the Fayetteville campus.

He helped build the Jerry Jones/Jim Lindsey Hall of Champions Museum in the Broyles Athletic Complex and served 10 years on the UA board of trustees, including a year as chairman.

His oldest son, Lyndy, became a four-year letterman for the Razorbacks’ football team. Lyndy Lindsey, 43, serves as president of golf operations and design for nearly 40 nine- and 18-hole courses that are operated by Lindsey Management.

When John David was a toddler, his father co-founded Lindsey & Associates with J.W. Gabel in 1973. The firm has grown to be the region’s dominant real estate investment and management company.

Lindsey & Associates has more than 200 agents in the region working out of offices in Fayetteville and Rogers, according to the company website, lindsey.com.

John David Lindsey graduated from Fayetteville High School in 1989 and from UA in 1994 with a bachelor’s degree in education.

He joined the Lindsey firm in 1996 as general manager of the Rogers office and assumed that position in 1998 for all locations, according to the company website.

On his public Facebook page, John David Lindsey describes himself as a Christian whose political views lean to the Republican Party. He likes country music and Elvis Presley, history and sports books, and hunting magazines.

Lindsey lists his activities as “watching my kids play sports” and “work work work.” He lists golf, hunting and “loving my kids” as his interests.

TRUST ISSUES

In his bankruptcy filing, John David Lindsey listed benefits in four trusts with unknown values, which drew legal challenges from the Bank of Fayetteville and Trans Lease.

On June 21, 2010, the two companies filed separate complaints in bankruptcy court charging that Lindsey deliberately provided misleading financial statements prior to his bankruptcy.

Trans Lease, in its complaint, submitted a supporting document: a financial statement provided by John David Lindsey when he applied for a loan with the company in the spring of 2008, on which he listed holding $52 million in equity in a trust.

According to a similar supporting document in the Bank of Fayetteville’s complaint, Jim Lindsey and John David Lindsey both signed a letter dated May 20, 2009, to the bank that listed John David Lindsey held 33 percent in the “JD Lindsey Irrevocable Trust” valued at $69 million.

According to court documents, John David Lindsey was due to receive half of that amount when he turned 40.

The bank’s complaint was dismissed with prejudice at the request of the bank’s and Lindsey’s attorneys on Dec. 27, 2010, which means the bank is forever barred from pursuing the charge.

Mary Beth Brooks, president of the Bank of Fayetteville, did not respond to requests for comment for this article.

MOVING ASSETS

In a 155-page document filed in bankruptcy court on March 16, 2010, John David Lindsey reported that both he and his development business were transferring assets in the months prior to his personal bankruptcy.

On Nov. 13, 2009, he transferred $1 million in private stock in Lindsey & Associates to his father.

Three months earlier, John David Lindsey Development LLC transferred 12 lots in Benton County worth a total of $582,083 to JEL Homes LLC, a company incorporated in 2008 by Jim Lindsey.

Four days later, John David Lindsey transferred to Jim Lindsey a total of $88,384 worth of stock in the First National Bank of Eastern Arkansas in Forrest City, General Electric and Tyson Foods.

On Dec. 30, 2009, he transferred hunting equipment valued at $64,890 to his father. The next day, his development company transferred a 2008 GMC Sierra pickup worth $22,500 to Jim Lindsey.

“John David told his dad for a year, a year-and-a-half, ‘Whatever you tell me to do, I’ll do it,’” Elsass said.

At the time of his bankruptcy, Lindsey estimated his monthly take-home pay to be $3,536, according to court filings. He also received a $5,000 monthly distribution from a trust.

He claimed $19,921 in monthly expenses, which included nearly $10,000 in alimony and child support, the filings showed.

His 2009 earned income totaled $166,866, including $73,682 from Lindsey & Associates, according to the filings.

He also earned $37,692 from Stephens Red Dirt Farm, the now-defunct dirt and gravel quarry west of Fayetteville.

Larry and Norma Stephens, who sold their property to J&A Mining — a Lindsey-owned company — in 2008, sued Lindsey in Washington County Circuit Court in January 2010.

The couple accused J&A Mining of stopping its mortgage payments while continuing to operate on the property, then leasing part of the property to a third party.

In June 2010, Lee, the court-appointed trustee, agreed to surrender 12 lots and another 80 acres in Washington County to the Stephenses for the unpaid balance of the $696,765 mortgage.

‘HUMBLED’

John David Lindsey’s lifestyle has changed significantly in the last two years, Elsass said.

Lindsey used to purchase a new truck every six to eight months, but he’s been driving the same truck since 2007, Elsass said.

Lindsey no longer uses the Lindsey & Associates private jet to travel, and he doesn’t spend as much money during business trips and vacations as he once did, Elsass said.

More significantly, Lindsey is no longer operating multiple companies from his sixth-floor office in the Lindsey building in north Fayetteville, Elsass said.

“He comes in every day, and he works with the real estate agents,” he said. “Back to the roots. No developing.”

Lindsey was “humbled” by his financial troubles, Elsass said.

“He told me not too long ago that the biggest thing that’s hurt him, more than anything, is the embarrassment to his family and the people that he hurt financially,” he said.

“Basically everything he tried to do, he tried to do to make his father proud,” he said. “He is working hard to build that back for his father.”