LITTLE ROCK — Carl Whimper was standing a few feet away from an Arkansas-Pine Bluff football coach who was both ultrasuccessful and a lightning rod of controversy when they finally learned the news they hoped would never come.

The coach looked down at a piece of paper that had been faxed to UAPB, read it and turned to Whimper.

“Carl, can you believe this?” he aked.

“Coach, what is it?” Whimper replied.

“They’re giving us the death penalty,” the coach said.

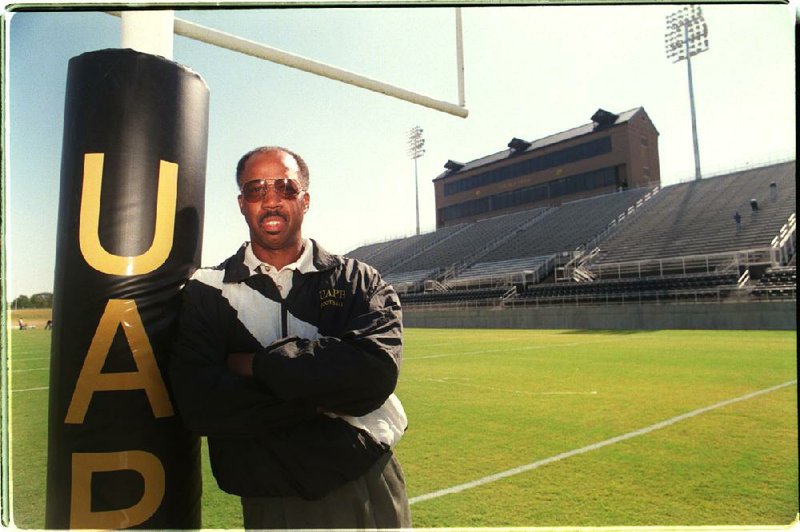

Just like that, after almost four seasons of soaring point totals from a pass-happy offense in front of overflow crowds at rickety Pumphrey Stadium, Archie “The Gunslinger” Cooley and the most successful run of football at UAPB was silenced by the NAIA in December of 1990.

UAPB’s former Arkansas Intercollegiate Conference rivals turned in around 100 allegations, requiring a year-long NAIA investigation that turned up enough truth — 41 violations involving 20 different players — to shut down the Golden Lions football program for the 1991 season.

Most of the violations centered on the eligibility of transfer players. One allegation included a redshirting player who was playing under different jersey numbers and names.

Cooley, who is retired in Fort Worth, denied most of them at the time and spent the early weeks of the 1990 season lashing out at his critics.

Whimper, who has been on UAPB’s campus for more than 40 years as a student, sports information director and university recruiter, said the length and scope of the investigation made it so penalties were expected. But they weren’t prepared to read what they saw that day on that piece of paper inside Cooley’s office.

Cooley pulled himself away from coaching early in that season, and he resigned after the penalties came down in December.

UAPB’s 9-1 finish that year — which would have been the school’s best season if not for having to forfeit all the victories — went for nothing. UAPB was not eligible for the NAIA playoffs because of the investigation.

Then, for two years, Pumphrey Stadium sat quiet along University Avenue, which slices through the eastern edge of UAPB’s campus.

Players scattered to instate schools and other black colleges in the South. Those who stayed spent their Saturdays playing intramural sports or traveling to see their buddies who transferred. The only games that were played at Pumphrey Stadium in 1991 and 1992 — the school voluntarily forfeited the 1992 season — were alumni flag-football games during homecoming celebrations.

“It seemed like a ghost town,” Whimper said. “It was really hard to take.”

LIFE AFTER DEATH

The NAIA hammered UAPB with the harshest of possible punishments — banishment of a team for one season, a penalty similar to what SMU received from the NCAA in the 1980s.

UAPB will conclude its 20th football season since emerging from the death penalty when it plays Jackson State at noon Saturday in the Southwestern Athletic Conference Championship Game in Birmingham, Ala.

A victory would give the Golden Lions (9-2) their first 10-victory season and outright conference title. Just being in the game is momentous for a program that had never won seven games in a season before Cooley arrived and considered being a part of a four-way tie for the 1966 SWAC title its most notable achievement.

“I want us to come out of the bottom to the top,” said Coach Monte Coleman, who is 28-27 in five seasons. “Not just one year, but for years.”

It has transformed itself from a black college also-ran that played in a glorified high school stadium to one of its state’s four NCAA Division I programs, one that ranks No. 2 in the Sheridan Broadcasting Network Black College Football Poll.

UAPB played for an NAIA national championship in 1994 after restarting in 1993 and realigned with its SWAC brethren in 1997, a move that facilitated the jump to Division I and created about a half-dozen new sports, and in 2000 opened 14,000-seat Golden Lion Stadium.

UAPB’s success in the SWAC has been sporadic, but it played for the conference title in 2006 and will do so again Saturday.

It’s more than what most thought possible when the school announced it was bringing back its football program after a two-year hiatus.

Roscoe Nance, who was working as a sports writer for USA Today at the time but has covered black college football for decades, said the perception was not that a sleeping giant had been awoken.

“I don’t think [fans] thought it would take awhile. I don’t think they thought it would ever happen,” Nance said. “You just thought they were another good homecoming opponent.”

‘WE CAN DO THIS’

Lee Hardman didn’t need to take the UAPB job in 1992.

Hardman, from Stuttgart, was a defensive back at UAPB from 1968-1971 and was a high school coach overseeing one of the state’s greatest dynasties at Pine Bluff Dollarway, winning four state titles and compiling a 63-1 record over his final five seasons that included a 51-game winning streak.

Hardman hesitated to make the move across the town after then-chancellor Lawrence A. Davis Jr. called about the opening in December of 1992.

“To leave all that [at Dollarway] and come over here to nothing?” Hardman said. “I had never been a college coach before, and to walk into something like that, I was a bit nervous. ... We were walking into an area that was dark.”

Following conversations with Davis that centered on an eventual new stadium, Hardman went to work rebuilding a roster that had scattered across the country following the death penalty.

He recruited some players from Dollarway and hit the other state high schools, something Cooley rarely did, selling them on a chance to play early and start something new.

“It’ll be something you’ll never forget,” Hardman told them.

Chris Robinson was recruited by Cooley out of Mobile, Ala., as a quarterback. He redshirted in 1989 and was a backup in 1990. He stuck around for one season after the death penalty but transferred to Southern, where Cooley was offensive coordinator, when the school chose to sit out the 1992 season.

He stayed one season at Southern, where he sustained a knee injury, then transferred back to UAPB with two years of eligibility left to help Hardman kickstart things.

“We had guys from Hawaii, Texas, Texas A&M, everywhere — guys who had dreams of playing,” said Robinson, who now works in the school’s recruitment office alongside Whimper and Hardman. “That first spring, we had 200 guys come out for football.”

UAPB streamlined its roster as the Golden Lions neared their first game, which was against Harding at War Memorial Stadium in Little Rock, but UAPB was forced to forfeit the 32-22 victory after it learned some players had played without proper eligibility forms.

UAPB avoided further penalty and, after the rough start, won its final three games to finish 5-6.

“We can do this,” said Robinson, recalling the team’s attitude following that first season. “We knew what SMU went through. We knew what people were going to expect, but that doesn’t mean we have to be in the same boat.”

Hardman instituted a practice regime that rankled his staff but one he still credits for the accelerated progress. With so many new faces, even after playing a season, Hardman started two-a-days with essentially two different teams. One was made up of veterans and the other was made up of freshmen, and each would go through practice twice a day.

“We were on the field all day long,” Hardman said, “but it gave us an opportunity to evaluate our freshmen, to see who could play and where they could play.”

Robinson led UAPB to victories in its first four games and a No. 7 national ranking in 1994. The Golden Lions beat No. 1 Central State (Ohio) in the first round of the playoffs and beat Western Montana 60-53 in overtime before 12,000 fans packed into Pumphrey Stadium to see UAPB’s 13-12 loss to Northeastern Oklahoma State in the national championship game.

“We will be back next year,” Hardman said after the loss.

UAPB never returned to such heights under Hardman. He coached nine more seasons, including consecutive 8-3 finishes in 1997 and 1998, and resigned after the 2003 season with a 63-57 record.

‘A CIRCUS’

Whimper let out a few laughs recalling the largest spectacle to ever hit an athletic department he’s followed since 1968.

“It was a circus,” said Whimper, UAPB’s sports information director at the time.

Whimper knew all about the NAIA’s investigation and how it dampened the mood around a team that is regarded as the school’s best.

UAPB would pummel teams on Saturdays under Cooley, winning by scores of 55-0 and 45-2 early that season, and during the week Cooley would lash out at critics in news conferences. Cooley took himself away from coaching in September while the investigation went on and Willie Fulton, who is now the athletic department’s business manager, became interim coach.

Fulton led UAPB to a 9-1 record in 1990, but there were no playoffs because of the investigation. In November, ESPN’s Chris Fowler spent two days in Pine Bluff for a report on the scandal.

“The problem is, is what they’re doing to a man that doesn’t deserve to be treated like this,” Cooley told Fowler. “For what reason? I don’t think they even know the reason.”

Whimper said one of the allegations centered on a redshirt quarterback, Winston Delaney, who played in road games under a different jersey number during one season. Whimper said number changes were so prevalent that it was hard to keep up, and it was easy to sit back and enjoy the fun.

“Anybody outside of the UAPB circle, they had no idea that this was going on,” Whimper said. “All they knew was that we were winning.”

Robinson said he and his teammates didn’t think the allegations would amount to much, but when Cooley took himself away from coaching on Sept. 28, 1990 — he remained athletic director — “we knew it was real.”

“This is Cooley,” Robinson said. “He’s invincible.”

The NAIA didn’t think so.

Cooley left Pine Bluff for Southern in 1992, then spent time at Texas Southern, as a head coach at Norfolk State, then as a high school coach in Texas before finishing his career at Paul Quinn College in 2006. Whimper said he still talks to Cooley from time to time and said that Cooley is still irked about how his time in Pine Bluff ended.

Phone calls placed to Cooley’s home weren’t answered, and Fulton declined to comment for this story and when he was asked in January 2011 while serving as UAPB’s interim athletic director.

“It’s a very touchy situation,” he said then. “People have moved on.”

Cooley’s legacy at UAPB remains complicated. There is no memorabilia of his teams displayed at Golden Lion Stadium or in its football offices, and Coleman said he rarely hears Cooley’s name or the death penalty mentioned.

For those at UAPB who knew Cooley, he’s remembered more for what he did than how he left it.

“There was just something about the atmosphere about that time,” Robinson said, “that helps you sneak in and you don’t want to let go.”

SWAC Championship

Game

WHO UAPB vs. Jackson State WHEN Noon Central Saturday WHERE Legion Field, Birmingham, Ala. RECORDS UAPB: 9-2; Jackson State 7-4 COACHES UAPB: Monte Coleman (28-27 in fifth season); Jackson State: Rick Comegy (156-81 in 21st season overall, 48-30 in seventh season at Jackson State) RADIO KUAP-FM, 89.7, in Pine Bluff TV ESPNU

Sports, Pages 19 on 12/07/2012