GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. — Something stunning happens at 60 miles per hour inside the UPM Blandin paper mill.

A thin layer of damp white pulp, flattened between forming fabric as it races through a gantlet of heavy rollers, slips free from its forms.

Rippling like a bedsheet on a clothesline, it holds together. The newborn paper shoots forward through heated rollers to be pressed and dried, then coated and polished before spooling onto a giant roll. More than 1,000 tons of shiny white paper for magazines and catalogs come off the line every day.

But this is yesterday’s miracle.

The North American paper industry is in rapid decline. Mills have cut thousands of workers and are competing in a shrinking market. A mill in Sartell, Minn., that closed this year after a Memorial Day explosion was the latest to go dark.

“It’s kind of disheartening,” said Jim Skurla, an economist at the University of Minnesota-Duluth. “Paper’s never going to disappear, but it’s going to be smaller than it has been.”

Forest towns from eastern Washington to Maine have lost more than a hundred paper mills in a wave of consolidation in little more than a decade — a trend most people in the industry expect to continue. Wisconsin has lost nine paper mills since 2005.

North American demand for three types of coated and supercalendared paper — shiny magazine and advertising paper — has fallen 21 percent in the past decade, according to the Pulp and Paper Products Council.

Kindles and iPads, email, PDFs, the decline of first-class mail, and waning newspaper and magazine circulations are all to blame. Analysts predict demand will fall at least another 18 percent by 2024.

The shift is forcing paper mills and mill towns to rethink their future. To survive, they will need to find new products to make out of wood.

“We’ve got to go somewhere,” said James Kent, the controller at UPM Blandin. “The world won’t need paper forever.”

Mill jobs pay well — averaging more than $20 per hour — and the mills support networks of suppliers, contractors and loggers, indirectly accounting for 20,000 jobs in Minnesota alone.

The mill in Grand Rapids opened in 1902 along a stretch of the Mississippi River that gave the city of 10,000 its name.

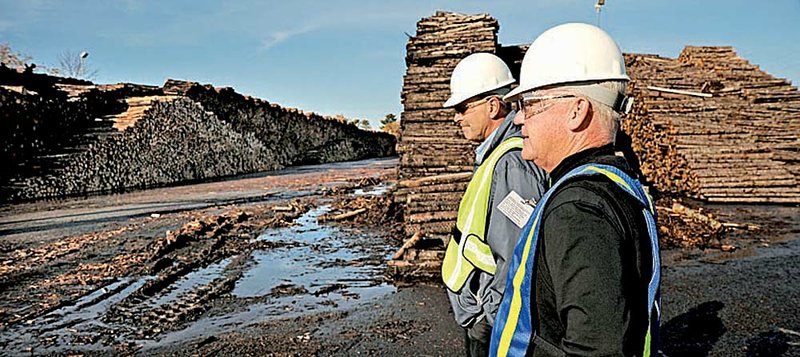

Almost all the trees it converts to paper are cut in Minnesota forests. Loggers truck the timber to the mill, where it gets stacked in piles as much as three stories high in a wood yard five football fields long. On the other end of the mill is a warehouse filled with metal shelves holding giant rolls of paper in brown wrapping.

About 450 people work at the mill, where most of the human labor happens at the beginning, at the end and in making sure the machinery in the middle doesn’t break.

From the moment the logs are dropped into a de-barking machine to the end of the line, the fiber moves by conveyor belt and pipe. The wood is chipped, ground, beaten and refined before it flows out to be flattened, pressed and dried as paper. Workers monitor the process from computers in glassed-in control rooms, sheltered from the roar and heat.

Paper companies have tried to handle sinking demand for their product by cutting production.

Companies have closed 117 American mills since 2000, according to the Center for Paper Business and Industry Studies at Georgia Tech University. Some 223,000 industry jobs have gone away in that time.

Today, demand is falling too fast for the cutbacks and consolidation to keep up.

Verso Paper, which closed the mill in Sartell after an explosion that killed a man and caused $50 million in damage, has never turned a real profit.

Created in 2006 when the private equity firm Apollo Global Management broke off a division of International Paper, Verso has lost money every year but 2009. That year, it got $239 million in federal tax credits for using a paper-making byproduct as an alternative fuel.

If not for the explosion, the mill would have kept running for a time, but it had already shut down two machines and cut 175 jobs in late 2011. Verso stock was trading at $1.12 a share when the explosion happened. When the mill closed permanently, leaving another 260 jobless, it was no surprise to the industry.

“The overall fact is demand is declining, and you could make a case that demand decline is going to accelerate going forward, so we’re going to see even more shuts at a more rapid pace,” said Paul Quinn, a paper and forest products analyst at RBC Capital Markets in Vancouver.

The foreign-owned paper mills in Minnesota — UPM Blandin and Sappi Fine Paper in Cloquet — are both working toward a future in which they produce something other than paper. The companies, like their American counterparts, struggle against the overcapacity that plagues the industry as they look for new business models.

South African-owned Sappi is spending $170 million to convert its pulp mill to produce chemical cellulose that can be turned into thread for textile mills. The Finnish parent company of the Blandin mill has invested in research of cellulosic nano-materials, which chemists believe could be blended with other materials to make car and aircraft parts, and maybe body armor.

But the clock is ticking, and government efforts can only temporarily prop up paper mills.

In October, a mill in Nova Scotia abandoned by NewPage a year ago started back up under Canadian ownership, in part because of $125 million in provincial incentives.

The paper industry in Maine cried foul at the subsidy because the mill can produce 360,000 tons of supercalendared paper each year. In 2011, that would have equaled 17 percent of North American capacity for that type of paper.

But subsidies are neither new to the industry nor exclusive to Canada.

U.S. mills got a gift during the recession when a favorable Internal Revenue Service ruling lavished them with $8 billion in federal tax credits for using “black liquor” — a byproduct of the paper-making process — as fuel. That’s how Verso achieved its only profitable year. Quinn, the analyst, said Canada followed with a billion dollars in new energy-efficiency credits.

“All you’re doing is you’re moving around the mills,” Quinn said. “The reality is the demand is going down. Some mills are going to have to come out.”

Business, Pages 61 on 12/02/2012