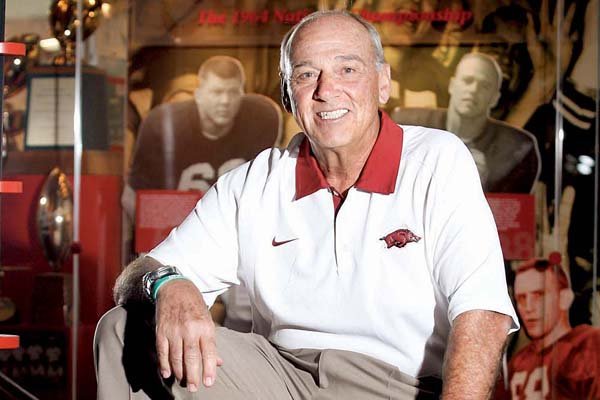

FAYETTEVILLE — What was John L. Smith thinking?

Day after day this summer, the 63-year-old head football coach of the Arkansas Razorbacks sprinted up and down the steps inside Donald W. Reynolds Razorback Stadium. More often than not, he chose to do it in the middle of the day.

On the surface, this seems crazy. Northwest Arkansas experienced record heat throughout the summer, and it would have been a lot less grueling to run the steps at, say, 6 a.m. than at midday.

An early-morning run certainly would have been manageable for Smith. Without using an alarm clock, he wakes up most days around 5 a.m., a habit that dates back to his boyhood on his family’s Idaho farm.

“It’s an automatic-body deal,” Smith says. “I tell our kids here, ‘Sleep’s highly overrated. You can get by with only four hours.’”

Smith could have hit the steps early in the morning, when the temperature was still in the mid-70s rather than the high 90s. It seems like the sensible thing to do, and certainly a less punishing way to stay in shape.

Had he run the steps at the crack of dawn, though, he would have done it in solitude. By doing it in the middle of the day, often while his players were on the artificial turf below, Smith was sending a message: You have to pay the price.

“He did it all the time [in Kentucky], and was better than half the team,” says New England Patriots wide receiver Deion Branch, who played for Smith at the University of Louisville. “It was something that had been implemented in our workouts by our strength coach, and [Smith demonstrated that] if our head coach can do this as our leader, we’re going to do the same thing as players. He just showed us by example.”

If you want to win, you’ve got to pay the price. As a head coach, Smith has won 46 more games than he has lost, and he has done so in part because he poured his life into coaching.

He “didn’t spend near enough time” with his three children when they were growing up, and feels guilty about it, as well as for missing out on so much time with Diana, his wife of 42 years. He’d like to be able to make that up with their two grandchildren, but as long as he’s a college football coach, he knows that it’s unlikely to happen.

The job demands too much ... or more accurately, Smith demands too much from himself.

“I’ve always told coaches who want to get into the profession, ‘Make sure your wife’s very independent and can do without you, because they’re probably going to have to raise the family. You’re not going to be around,’” Smith says.

Yet there’s more to life than football. Smith tells his players and coaches this message all the time — not through words, but in the way he lives.

He has run with the bulls in Spain. He has climbed Mount Kilimanjaro, jumped out of an airplane, and paraglided over Switzerland.

There’s a lot left on his list. He wants to climb the Grand Tetons, float the Grand Canyon, and run a marathon.

“He showed us — he didn’t speak about it — through his lifestyle and the things he did,” Branch says. “What we took from him is that life is bigger than what’s going on now. He’s a head coach, and he has all these obligations he has to attend to, but the most important thing [he taught] is that we don’t get stuck on what we’re doing, that there’s a life outside of just playing football.”

THE KID FROM IDAHO

If Smith hadn’t become a football coach, he would love to have been a ski bum.

He has alpine downhill skied his entire life, often near his family’s home in Iona, Idaho, or in nearby Jackson Hole, Wyo.

“Skiing is big in my family; we would ski almost every weekend,” Smith says. “[Being a ski bum] is a goal I never got to in this world. That would have been the great life.”

Physically, Smith could have been a ski bum, and he certainly has the adventuresome spirit to have spent a lifetime on the slopes. Mentally, though, there’s no way he could have done it; by definition, being a ski bum requires a relaxed attitude that Smith doesn’t possess.

Although his father, the late Robert J. Smith, was a banker by trade, the Smith family had a 40-acre farm in Iona where they raised cattle. John L. Smith grew up in a family where hard work was expected, where he and his four siblings were expected to get up at 5:30 in the morning and help with chores.

There were more chores to do after they got home from school, but there was one way out: If the kids were involved with sports, and thus practicing after school, they didn’t have to do any chores that night.

Smith made excellent use of this escape clause, playing football, basketball and baseball, running track, and even participating in rodeos.

“That was reason for us to say, ‘I’m going to go out for everything,’” says Smith, who in 2000 was named by Sports Illustrated as one of Idaho’s top 100 athletes of the 20th century. “If you couldn’t run, you’d go out for track, just so you wouldn’t have to do your chores.

“It was a good place to grow up. I think any time you grow up in that rural setting, you learn to get up and you learn to work hard.”

With his intense work ethic, Smith naturally was drawn to coaching.

He was a good student as a kid, one whose grades would have been better had he not cut school so often and traveled across town to secretly watch high-school football practices. Smith looked on in awe as the coach readied his players for games, and he knew that was what he wanted to do as an adult.

Smith played quarterback at Bonneville High School under Coach Ralph Hunter. Before Smith’s senior year, Hunter accepted a coaching position at Weber State University (Ogden, Utah), and then recruited Smith to come play quarterback and linebacker.

“My high-school coach had the biggest influence on me, other than my parents,” Smith says. “Ralph Hunter was like a second father to me. He would just kick you in the tail when you needed it, and give you a hug when you needed it.”

A TRUSTING COACH

That level of perception, to know what kind of words a person needs to hear at any given moment, is often attributed to Smith.

“He always had a saying, ‘You’re either getting better or getting worse,’” says Detroit Lions offensive coordinator Scott Linehan, who was an assistant coach under Smith at Idaho and Louisville. “He was always on you when things were going well, and when they weren’t, he was a calming influence. He had a real pulse of the team.”

In this respect, understanding how to motivate players and assistant coaches, Smith is like Hunter. He’s not a carbon copy of his high-school and college coach, though; rather, he’s a blend of all the coaches he has worked with.

That means he has some of Jack Swarthout in him, having coached under Swarthout at Montana in the 1970s. He has some Dennis Erickson in him, from serving as Erickson’s defensive coordinator at Idaho (1982-’85), Wyoming (1986), and Washington State (1987-’88).

(It was during the time at Idaho when the “L” was added to his professional name, to provide clarity with two other John Smiths on staff; he has repeatedly refused to tell people what it stands for.)

And it means he has some Bobby Petrino in him. Smith coached special teams and outside linebackers at Arkansas the past three seasons under Petrino, then left to become the head coach at Weber State in December 2011. Following Petrino’s dismissal, he returned in April to become the Razorbacks’ head coach.

Smith says it’s important to constantly refine himself as a coach, explaining that “Once I’m green, I’ll continue to grow, but once I’m ripe, I’ll soon be rotten.”

“As a coach, you’re a product of the people you’ve been with and how you’ve been raised,” Smith says. “My philosophy is, ‘I will adopt the things you do that I think are good and will fit.’”

Following a year as a graduate assistant, Smith spent 17 seasons as an assistant coach at five different schools. Along the way, he learned that a good head coach puts a lot of responsibility on his assistants.

In November 1988, Washington State held a late 34-30 lead at No. 1-ranked UCLA. UCLA was threatening to score the game-winning touchdown, and had first-andgoal at Washington State’s 6-yard line.

Smith asked Erickson what they should do. Erickson answered that it was Smith’s decision to make, that this was the reason he had been hired.

It was a telling moment for Smith. Washington State made a goal-line stand and shocked UCLA.

“Some guys are big-time micromanagers, and while he’s not hands-off — he’s got his hands on everything — everyone knows what their roles are, and he allows them to do it,” Linehan says. “I think [assistants] know they’ve got a guy that trusts them, and by holding everybody in the program accountable, they’ll do the job the best they can.”

BACK IN THE SADDLE

It’s a rare day that Smith doesn’t wear cowboy boots.

They’re a throwback to his childhood, to the calf roping the Smith children would do in their backyard. He has worn cowboy boots at every stop in his career, from the Pacific Northwest to Louisville.

He jokes that “these boots weren’t going to work real good in Miami,” so when Erickson left Washington State to coach the University of Miami in 1989, Smith struck out on his own, returning to Idaho to take his first headcoaching job.

He went 53-21 in six seasons at Idaho, setting a school record for victories and leading the Vandals to the NCAA Division I-AA playoffs five times. From there, he coached Utah State for three years, winning two Big West Conference championships at a school that had previously had just two winning seasons in 15 years.

Throughout his career, Smith says he never was looking to move up to bigger programs.

“My goal has been the present,” he says. “The way I’ve been is, do the very best we can do right now where we are, and the good Lord willing, doors will be open. ... It comes back to: big time is where you are.”

Next came Louisville, where he inherited a team that had gone 1-10 the previous season. Smith went 41-21 in five seasons, leading the Cardinals to a bowl game every year. In 2001, he coached Louisville to a school-record 11 victories and won Conference USA Coach of the Year honors.

Dave Ragone, currently a wide receivers coach with the Tennessee Titans, played quarterback under Smith at Louisville. Ragone says Smith succeeded because the players knew he cared about them, and he was able to change the culture of the program.

“He does a great job of rallying the troops and getting the discipline level up,” Ragone says. “He turned us from an afterthought to the thing going pretty much full tilt ... and that goes back to the fact that each athlete knows he cares.”

Smith took over at Michigan State in 2003, and he got off to a great start, winning the Big Ten Coach of the Year award in his first season in Lansing. Then, for the first time in his career, he hit an extended rocky patch, and after three straight losing seasons, he was let go by the school following a 4-8 record in 2006.

Linehan, the coach of the St. Louis Rams at the time, brought Smith on board to be a scout. He did that for a year, then spent the next year hosting a morning talk show in Louisville.

It was a fun gig for Smith, and one for which he was well-suited. He has long had a reputation as being one of the most-quotable coaches in college football, someone who can effortlessly fill up a reporter’s notebook.

Smith has always been comfortable dealing with the media, because it’s easy for him to talk to people. Famously, he shouted at an ESPN sideline reporter in 2005 that, “The kids are playing their tails off, and the coaches are screwing it up!”

“He’s a guy who’s not going to sugarcoat things,” Ragone says. “He’s trying to be transparent, and he believes it’s a relationship business. He doesn’t want to hide anything.”

The talk-show job was fun for Smith, but he knew that he wasn’t finished coaching. He got back into it in 2009 when he was hired to coach at Arkansas by Petrino, his onetime assistant at Louisville.

That fact that former assistants were willing to help Smith get back on his feet after his dismissal is not surprising. Smith is fiercely loyal to the players and coaches who are willing to pay the price, engendering a great deal of loyalty in return.

“There’s not anybody who has worked for John L. who doesn't understand he bases everything on loyalty,” Linehan says. “That’s one of his biggest strengths.”

Loyalty weighed heavily on Smith’s mind this spring, when he considered taking the Arkansas job. He had just begun at Weber State, and wondered whether his loyalty was greater at his alma mater or at Arkansas, where his players were dangling in uncertainty after Petrino’s firing.

His wife made the answer clear to him: He had to go to Arkansas. His players were there, and it was a chance to coach at a school where a national championship was a possibility.

“She was right,” Smith says. “The door opens, what are you going to do? Are you going to sit on this side of it? Let’s go!”

SELF PORTRAIT

John L. Smith

DATE AND PLACE OF BIRTH Nov. 15, 1948, Idaho Falls, Idaho

ONE THING THAT SURPRISED ME ABOUT MOVING AWAY FROM IDAHO FOR THE FIRST TIME I thought the wind blew every place every day like it did in southeast Idaho.

MY BIGGEST CONFIDANT IS My wife. She’s very understanding, thick-skinned and can put up with all my crap.

RUNNING WITH THE BULLS WAS A great experience. I got to see Spain. One guy I could understand was [Ernest] Hemingway; I always read all his books, so that was a contributing factor as well. I got to sit where Hemingway sat.

WHAT I TRY TO DO IN PREGAME SPEECHES IS

Give a little bit, not make it too long or too boring. I’ve always tried to let my assistants speak as well; that’s important training for them.

REACHING THE SUMMIT OF MOUNT KILIMANJARO WAS An amazing experience; you’re up in the clouds when the sun comes up and you can see the world.

I’M A BIG BELIEVER IN Regimentation. Our whole week is pretty much regimented. It’s important for players [that] we do the same things week in and week out.

AS I’VE GOTTEN OLDER, IN SOME CASES I’VE BECOME More patient, in some cases I’ve become less patient.

HOSTING A TALK SHOW WAS Great. I could get up in the morning and say whatever I wanted to say. It was a fun deal, and I didn’t make one mistake.

WHEN I JUMPED OUT OF AN AIRPLANE I kept thinking, ‘‘This will be something to get me over my fear of heights.’’ It didn’t help.

MY WIFE AND I MET In junior high. We were born in the same hospital, one day apart. She’s an older woman, robbing the cradle.

ONE PHRASE TO SUM ME UP Don’t live life asking, “What if?”

High Profile, Pages 54 on 08/26/2012