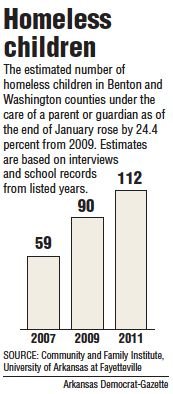

FAYETTEVILLE — The number of homeless children nearly doubled in Benton and Washington counties since 2007 as families struggled during the worst recession in decades, according to a report a University of Arkansas professor released Thursday.

“People stereotype the homeless as being a 40- to 50-year-old man with a cardboard sign, but that’s not the case,” said Jon Woodward, director of the Seven Hills Homeless Center in Fayetteville. “Who is homeless here are basically young families.”

Families — often women with children — are struggling to maintain stable homes in the face of job cuts and wage reductions, combined with a lack of affordable housing, said Kevin Fitzpatrick, Community and Family Institute director at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville. The university led volunteers in the region’s effort to count homeless residents as part of the Point-In-Time Homeless Census, a national snapshot that concluded Jan. 28.

Fitzpatrick expects to report to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development about 300 homeless adults living in shelters and homeless camps during the census in Benton and Washington. However, the report Fitzpatrick released Thursday also includes children and adults with no permanent home, including those who report staying with friends or relatives.

HUD requires the census of homeless residents every other year.

In 2009, Arkansas was one of 23 states that reported fewer homeless people than were counted in 2008, the last years for which national statistics are available. On Jan. 27, 2009, volunteers in the Little Rock area counted 1,425 homeless people staying in shelters or on the streets. A similar count in 2008 reported 1,811 homeless people.

HUD will review the census counts in May, said Jimmy Pritchett, Little Rock’s homeless coordinator, with official numbers not being released until “probably early summer,” he added.

But Fitzpatrick said the numbers required by the federal government don’t show the entire picture of homelessness. He calculates the number of children based on interviews with homeless adults and data provides by school districts.

“I think it’s an important part of the homeless story,” he said.

Including children and adults with no permanent home increases the count of Northwest Arkansas’ homeless dramatically. Fitzpatick’s report says the area’s homeless population jumped from 1,287 in 2009 to 2,001 in 2011 — a 36 percent increase. But the most significant finding is that the number of homeless children in kindergarten through 12th grade increased from 638 in 2009 to 969 in 2011, Fitzpatrick said.

The federal government uses a more narrow definition of homelessness, but Fitzpatrick said his calculations paint an accurate picture of homeless families.

“We’re no longer just serving [homeless] adult men,” Fitzpatrick said. “We need to think about what to do to [assist] women and small children.”

Although shelters and service providers are meeting the homeless population’s short-term needs, they aren’t equipped to deal with longterm housing needs Fitzpatrick said are required to break the homeless cycle. Some homeless people have problems with addictions, domestic violence, mental health issues or physical disabilities, said Major Tim Williford at the Salvation Army in Fayetteville.

The shelter has a space set aside for families in Fayetteville and Bentonville, both of which are routinely full, but the shelter isn’t seeing more families than previous years, Williford said. Fitzpatrick said a lot of children and families are not in the shelters but show up at food banks, churches and soup kitchens seeking help. Some might not consider themselves homeless and choose not to use services, he said.

Fitzpatrick said homeless people need a home before they can deal with issues like drug and alcohol abuse. Not everyone at the shelters are addicts, some just have bad luck, Woodward said.

“Nationally, what are we? A paycheck or two away from homelessness?” he said. “These people are your neighbors.”

About 25 percent of the people who seek help from the Salvation Army have lost their jobs, Williford said.

Hundreds of homes in Benton and Washington counties have fallen to foreclosure in the past few years, according to county clerk records. Fitzpatrick said that during the time foreclosures peaked in Northwest Arkansas, the number of families camping outside, living in shelters or living with family or friends rose sharply.

Benton and Washington counties have higher homes prices than those in more rural areas in Arkansas, said Jason Wiles, Metro Realtors owner and a Realtor.

In 2010, the average cost of a home was $164,452 in Benton County and $157,723 in Washington County, according to the Arkansas Realtors Association. Northwest Arkansas home prices are on par with the Little Rock area, Wiles said, but the average home price statewide was $144,389 last year, according to the association.

At the same time, rent in Arkansas has continued to rise over the past decade, said Linda Couch, senior vice president for policy at the National Low Income Housing Coalition. The coalition advocates public policies to help the lowest income residents in the U.S. have an affordable home, according to its website.

A minimum wage job won’t cover an apartment in Arkansas unless the worker puts in 63 hours a week, according to coalition findings. In the Fayetteville-Springdale-Rogers metro area, the average two-bedroom apartment costs $655 a month, meaning a 69-hour work week for an individual earning the state’s minimum wage of $7.25 an hour.

“There is an obvious and direct link between homelessness and affordable housing,” Couch said.

Arkansas, like the rest of the nation, doesn’t have enough low-income housing to go around, she said.

Nationally, 7.1 million households were using at least half their paychecks to cover rent or were living in inadequate housing. That’s up from 5.9 million in 2007, according to a February report by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The main problem is high rent and low wages in an economy that continues to lag in job creation. The need is out pacing the supply of affordable housing, Couch said.

Arkansas has 14,000 units of public housing for low-income families, but there’s not enough money to maintain the buildings or build new ones, so they are slowly closing down, Couch said.

“Until there are affordable places for people to live, we will likely be suffering the consequences,” Couch said.

On Thursday, the U.S. House Budget Committee announced plans to cut funding for programs tied to affordable housing, including rent vouchers that help more than 20,000 families in Arkansas, Couch said. Those families earn an average income of $10,346, she said.

One local program that helps low-income residents with housing is no longer accepting applications.

Seven Hills created a program in 2009 that served about 300 families to help them stay in their homes or rent a new one, Woodward said. Seven Hills ran out of grant money in the first few months.

Woodward said the project used grant money to provide counseling that helped families keep their homes and helped them make a rent payment or deposit. The idea was to keep families out of the shelter system, he said.

“The need was overwhelming,” Seven Hills Financial Coordinator Julie Drager said.

The nonprofit hopes to restart the program in July, but the state might not fund it, Drager said. The center, which serves an average of about 100 people a day, uses programs like the one for families to help people from becoming homeless, Woodward said.

“That’s what most people need — is just one thing to go right for them,” he said.