LITTLE ROCK — Finding out how many vehicles the state owns, who uses them and for what is a complicated and confusing process, perhaps beyond achieving.

The state Department of Finance and Administration, headed by Richard Weiss, longtime aide to a string of governors, keeps track of most of the vehicles the state owns.

But even with Weiss answering question after question from the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette throughout last week and digging out facts and figures, the quest for precision became like a hall of mirrors.

At the start, it was simple. The state owns 8,653 vehicles, Weiss said.

And the policy on their use is for-official-business only, as he put it unequivocally: “No one is authorized to use state vehicles for anything other than official business. In other words, there is no one authorized to make personal use of a state vehicle.”

If only it were that simple.

First, “official business” - the only legitimate purpose for using a state vehicle - allows some employees to use the vehicles for commuting between home and work.

How many?

Weiss says in an e-mail it’s 132 - 72 in higher education, 60 elsewhere in the government.

So only 132 get to use the cars to commute, but for them it’s not considered “personal use.”

When he provided a more detailed report on “commuters,” he found 292.

He explained that the 292 included some whose jobs are to be responders who head out from home in the middle of the night to deal with emergencies. And some are forest rangers who take vehicles into the woods as offices on wheels when they’re on duty. And so on.

So 292, not 132.

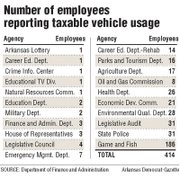

Then when asked how many state employees paid income taxes for (presumably personal) use of state vehicles, he found 414. Not 132, not 292, but 414.

The reason: His earlier reports covered the executive branch agencies over which the governor has direct authority. But the governor doesn’t have authority over everything.

The Highway and Transportation Department, which is authorized to have thousands of vehicles, is constitutionally independent thanks to Amendment 42, the Mack-Blackwell Amendment.

The Game and Fish Commission, authorized to have hundreds of vehicles, is constitutionally independent under Amendment 33 and perhaps also Amendment 75.

Other state constitutional officers (lieutenant governor, attorney general, secretary of state, auditor, land commissioner, treasurer) are independent.

And under Amendment 33, even higher-education institutions have some degree of autonomy under their boards of trustees.

Also not under the governor’s control are the judicial branch (the supreme, appeals, circuit and district courts) and the legislative branch (the House, the Senate, the Legislative Audit Division, the Bureau of Legislative Research, the Legislative Council).

So the list of 414 is bigger because it includes some of those other parts of the state that aren’t directly under the governor.

In fact, 186 of the 414 are Game and Fish employees who paid taxes for use of a state vehicle.

At that point in the inquiry even the widely respected Weiss was ruefully aware of the complexities. “It’s complex, I know,” he chuckled.

Agencies independent of the governor have their own policies on vehicle use, though some mirror the state’s general policy.

Weiss explained his distinction on what’s personal and what’s nonpersonal commuting this way: “In my mind, if you use a car to go to the store, or movie or vacation or anything other than going to work and back would be personal use. When I get home the car is locked up until I come back to work. For everything else I use my own car or truck.”

Governors at least as far back as David Pryor (1975-79) have struggled to get a handle on state cars - the cost of buying them, maintaining them, and deciding who gets to use them and for what.

One of the most extensive efforts came in the early 1980s when Bill Clinton issued Governor’s Policy Directive 3, “Purchase and Use of State Vehicles,” a policy reissued by subsequent governors since then with only slight modification, said Weiss.

Recent reports that elected officials and state employees used taxpayer funded vehicles for personal purposes make Governor’s Policy Directive 3 interesting reading. Its intention is “to place strict controls on the size and use of the state’s fleet of passenger vehicles” to make it “as efficient as possible by encouraging the use of fewer, smaller, and more gas-saving cars.”

It starts unequivocally:

“1. All passenger vehicles for each department and agency shall be pooled (i.e., not assigned to any individual for his or her own exclusive use) so that they are available for use by any employee on official business.”

“2. All state vehicles shall be parked at the agency location at night and on weekends.”

“3. All state-owned cars ... shall display red state license tags, front and rear. All state vehicles shall display appropriate side decals. Provided that when the interests of the state would be furthered by not displaying identification, such as law enforcement, exception to this directive may be obtained upon written approval of the governor.”

“4. All state departments and agencies shall place stringent control on the use of state-owned vehicles to ensure that they are used for ‘official use only.’”

Governor’s Policy Directive 3 also allowed exceptions “upon written approval of the governor.”

The exceptions would be good for the biennium in which they were granted.To continue, they’d need to be renewed. Though the decision to grant or deny exemptions is assigned to the governor, the policy calls for “fully supported requests” to be submitted to the Finance Department, whose director the governor appoints to do the governor’s bidding.

The basis upon which the state would assign a vehicle to an employee rather than reimburse him for using his personal vehicle on official business would be the financial advantage to the state. To determine that, the directive set up “break-even points” based on the size of vehicles and miles driven on business.

Most current exceptions to Governor’s Policy Directive 3 have been around a while. Gov.Mike Beebe’s office says his administration has added only one in his 3 1 /2 years as governor: for Cissy Rucker, administrator of the Arkansas Career Technical Institute.

“We felt it was fitting for someone with her qualifications and responsibilities in that position,” said Beebe spokesman Matt DeCample.

When it came to signing off on renewals, “we have authorized the ever-capable Director Weiss to handle” them, DeCample said.

The number of state employees has grown by thousands since the early 1980s.

The number of state cars has grown, too, though it’s not possible at this point to say how many the state had when Clinton issued his directive aimed at reining in the number of vehicles.

“Too much water has passed under the bridge” to know, Weiss said.

With Weiss’ report saying that 186 Game and Fish employees paid taxes for vehicle use, commission media specialist Kim Cartwright was asked why commission employees were allowed to make presumably personal use of state vehicles.

Cartwright said the commission’s current vehicle-use policy was developed more than 20 years ago and has been periodically revised. Cartwright also said the policy received review and approval by the Legislature.

It appears from her further response that commuting is allowed but isn’t considered personal use: “Employees have historically been allowed to use AGFC vehicles for business purposes including commuting between home and work location. AGFC longstanding policy has prohibited personal use of AGFC vehicles.”

Although the state doesn’t consider commuting between home and work to be personal use of the state vehicle, the Internal Revenue Service counts such use as a taxable benefit, a point spelled out in Game and Fish Commission rules for employees.

And the state Department of Finance and Administration follows the IRS rule in tax matters even though it doesn’t consider it to be personal use under the official policy on use of state vehicles.

Also, practices vary among state officials.

For example, in the office of Secretary of State Charlie Daniels, eight employees made personal use of state vehicles and paid income taxes on it, his office reports, while Daniels made personal use and didn’t pay taxes (but says he will now that he knows better). By the by, his official office policy is that vehicles are for official use only, but commuting is not only allowed but required for those eight employees, a use that isn’t “personal” under the official office policy, said a Daniels spokesman.

But in the office of Attorney General Dustin McDaniel, employees did not make personal use of state vehicles, except that McDaniel did and didn’t pay income taxes, but now says he has paid for the past-due taxes and has given up his state vehicle.

Sometimes getting a handle on state-car use falters because agencies don’t do their jobs on time. Arkansas Code Annotated 25-1-110 says each agency is to provide Weiss’ department a report that includes how many vehicles it has, the mileage on the vehicles, any private-car mileage reimbursement, and justification for keeping vehicles identified as underutilized.

The department uses that to compile an annual report to legislators in August-September.

The aim is to not be spending money on unnecessary vehicles and not be reimbursing employees for use of their personal vehicles on official business if it would be to the state’s advantage to provide a vehicle. (In fiscal 2009, the state paid $16,332,350 to reimburse employees who did official state business while using their personal vehicles,Weiss said.)

The deadline for such reports is June 1.

But some agencies simply don’t meet the deadline. Occasionally they don’t even start putting the report together until a month after the deadline.

There is “not really” any penalty that is applied to agencies for being late, Weiss said.

“Our goal is just to work with them so that useful information is reported to the Legislature,” Weiss said.

And, by the way, this law declares that the reporting requirement doesn’t apply to the Arkansas Lottery Commission, institutions of higher education and vocational technical institutes.

Another section of law, A.C.A. 19-4-906, is where the Legislature sets limits on how many vehicles agencies are allowed to have.

Some of the limits set therein (these are not necessarily the number the agencies have, but are supposedly the maximum allowed): Highway Department 2,300; state police 725; University of Arkansas-Fayetteville 594; Department of Human Services 444; Game and Fish Commission 400; Forestry Commission 396; Corrections Department 254; Arkansas State University 131.

The full list adds up to7,771, said Kim Arnall of the Bureau of Legislative Research.

To explain why the legal limit of 7,771 is smaller than the actual number of 8,653, Weiss points to two other provisions of the law.

One of them allows agencies to go over the limits if the governor by declaring an emergency allows it. Beebe has declared 21 such letters allowing 182 vehicles, Weiss reported.

The other section of law says that although the law sets limits on the number of vehicles for the Human Services Department and for higher-education institutions, it also appears to say that the department is exempt from the limiting law. However, one legislative lawyer said he thinks that exemption applies only to cars the department buys with federal funds (which may also involve some matching state funds).

This same section also says that vehicles donated to higher education for use primarily in auto-repair courses or truck-driving courses and such don’t count as part of the institution’s total even if they wind up being driven sometimes by the institution’s personnel.

Those additional or uncounted vehicles are part of the actual total, causing it to be greater than the authorized maximum, Weiss said, adding that he “will also admit that I have been remiss in enforcing this section of the law” when he adjusts the state vehicle numbers annually for updated legislation on vehicle limits.

But that still leaves the actual number of vehicles about 700 above the legal maximum.

Then, Weiss said, he learned from his staff that the 8,653 was not right in the first place because it includes motorized forms of transportation that may be driven on college campuses and in state parks but are not licensed for use on roads.

But when his department provided a full report, the vehicles appeared to be all standard vehicles, and the count seemed to be 8,654 rather than 8,653.

Front Section, Pages 1 on 07/25/2010